Revista Geográfica

ISSN: 1011-484X

Número Especial I Semestre 2017

Doi: dx.doi.org/10.15359/rgac.58-2.2

Páginas de la 15 a la 40 del documento impreso

Recibido: 1/8/2016 • Aceptado: 7/11/2016

|

Revista Geográfica ISSN: 1011-484X Número Especial I Semestre 2017 Doi: dx.doi.org/10.15359/rgac.58-2.2 Páginas de la 15 a la 40 del documento impreso Recibido: 1/8/2016 • Aceptado: 7/11/2016 |

Tourism and territory on the banks of lake Atitlán, Guatemala

Turismo y territorio en las márgenes del lago Atitlán, Guatemala

Álvaro Sánchez-Crispín1

Enrique Propin-Frejomil2

National Autonomous University of Mexico

RESUMEN

Este trabajo tiene como objetivo explicar el arreglo territorial suscitado por el crecimiento reciente de la actividad turística en uno de los lugares emblemáticos de Guatemala, el lago Atitlán. Alrededor de éste, y en un marco geográfico-físico imponente, se encuentran diez poblados, de origen maya y de lenguas kaqchiqel y tz’utujil, de pequeño tamaño demográfico, con una cultura viva diversa y que tratan de hallar su nicho en un mercado turístico altamente competitivo. Para lograr esto, en primera instancia, se hace alusión al escenario de acogida del turismo a partir de una explicación geográfica general del país y en particular del lago, de las áreas naturales protegidas, ya que el lago se encuentra inserto en una de ellas, la Reserva de Usos Múltiples de la Cuenca del lago Atitlán, y de la propia actividad turística. Enseguida se procede a explicar los principales centros de la economía del turismo en el lago y se reflexiona acerca de la relación inexistente entre la promoción de estos lugares y la presencia del área protegida.

Palabras clave: Geografía del turismo, territorio, lago Atitlán, Guatemala.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to explain the territorial syntax of tourism in one of the most emblematic places in Guatemala: Lake Atitlán. Located on the banks of this body of water and set against a spectacular natural background are ten small settlements, all of Mayan origin with a predominately kaqchikel- or tz’utujil-speaking population and a diverse living culture. These communities are trying to gain access to a niche segment of a highly competitive tourism market. In order to achieve our research objective, we first examine the geographical setting of tourism at both the national and local levels and also pinpoint some of the relevant features of protected areas in Guatemala, given Lake Atitlán’s location in the Lake Atitlán Watershed Multiple-Use Reserve, connecting it all back to tourism. Finally, we reveal the major tourist centers at the lake and end with a remark on the apparent non-existent relationship between tourism and the natural protected area in question.

Keywords: Geography of tourism, territory, lake Atitlán, Guatemala

Introduction

Over the last two decades, tourism in Central America has gained momentum due not only to proposals made by the different national governments themselves, but also to joint efforts by the seven countries that chain down the Central American isthmus to promote the region as a destination of preference within the context of an increasingly competitive world market. These nations boast a diversity of resources, both natural and cultural, on which to support the expansion of the tourism sector. Many studies have proposed typologies of places where tourism is considered to be an important economic activity, particularly in the case of Central America (cf. Sánchez-Crispín and Propin, 2010). In some countries, the sector’s growth is based on the availability of natural resources; for example, areas surrounding active volcanoes, such as La Fortuna, Costa Rica, in close proximity to Arenal Volcano; the port of Bocas del Toro in Panama, near the pristine beaches of Colón Island; and Moyogalpa on Ometepe Island, Nicaragua. However, the Central American country with the largest number of cultural resources for the promotion of tourism is Guatemala (Ibid.). Diverse elements, both tangible and intangible, that shape the geographical landscape of Guatemala, such as the living Mayan culture or different archeological sites, are at the foundation of the promotion of tourism in the country. Yet, another type of resource exists in Guatemala that has been incorporated into the country’s tourism dynamics since the late nineties: natural resources. These include natural protected areas that, in keeping with global trends that dictate that these should be places of preference for the introduction of sustainable tourism, are already widely visited by tourists and, as a result, contribute to restructuring the local economy. The purpose of this research paper is to explain the current territorial syntax as a result of the introduction of tourism to Lake Atitlán, located within one of the oldest protected areas in the country: Lake Atitlán Watershed Multiple-Use Reserve (RUMCLA), while, at the same time, revealing whether a relationship exists between the existence of this reserve and the promotion of tourism in the area.

Geographical Basis for Tourism in Guatemala

Guatemala boasts a wide variety of landscapes that are ideal for tourism: volcanoes, rain-forests, caves, caverns, rivers, beaches. The country can be divided into two parts in terms of predominant topography: the northern sector, known as Petén, is part of the great lowlands associated with the Yucatan limestone platform, while the south-central region is known for its mountainous landscapes and volcanoes, bordering on the Pacific Ocean via a narrow littoral zone (Sánchez-Crispín et al., 2012). While Guatemala’s geographical location would indicate a prevalence of tropical climates, in reality these are interspersed with mild and even cold climates in the highlands of the central region (Luján, 2011). Surface water resources are abundant given the wetter varieties of the tropical and mild climates that cover the majority of the national territory; in particular, Motagua River and those that make up the upper Usumacinta system are potential stages for the introduction of tourism in upcoming years. Lastly, the country’s level of biodiversity is a basic element for the expansion of tourism given the autochthonous plants and birds that inhabit both the warmer and milder climates.

Culture and lifestyle are varied in Guatemala. There are 23 officially recognized languages, the majority of which pertain to the Mayan language family (Ibid.). In this context, iconic settlements in the country’s central mountains, such as Chichicastenango (traditional indigenous market) and Antigua (with invaluable architectural heritage), have been heavily promoted among tourists. Moreover, it is important to mention that a significant percentage of the Guatemalan population lives in rural conditions, which could be considered a favorable situation for the practice of new forms of tourism that have become popular around the world and that are included under the umbrella term “ecotourism.”

The most populated city in the country, the national capital, serves as the point of arrival and departure for international tourists arriving in Guatemala via air. According to Teer et al. (1999), the country possesses world-class natural and cultural resources in Antigua, Tikal and Lake Atitlán. Although not the majority of visitors arriving to the country (only 27%; INGUAT, 2014), travelers who enter through the airport in Guatemala City, including Americans and Canadians (25% of total foreign tourists registered in 2014; Ibid.), then set out to the different sites characterized by their singularity, such as the archeological site of Tikal or the colonial city of Antigua, or to hike Agua and Pacaya volcanoes (Domínguez, 2012). In 2014, the country received more than 2 million tourists, more than double the number registered in 2003, almost half of which were from other Central American countries, mostly El Salvador and Honduras, and arrived by land (INGUAT, op. cit.).

The country lacks adequate accommodations, however, particularly in terms of superior quality hotels. International hotel chains manage few locations in Guatemala, most under the long-term rental system, and only in the national capital and a few major tourist areas, such as the city of Antigua (Sánchez-Crispín et al., op. cit.). The vast majority of rooms and properties that attend to the lodging needs of tourists, both national and foreign, are owned by Guatemalan or Salvadoran investors and are of inferior quality compared to the large global chains.

Moreover, the country’s road infrastructure is still too deficient so as to drive tourism in certain areas. There is only one main highway in the country (the Pan-American Highway), which connects the southern region of Guatemala with Mexico and El Salvador. The roads that connect the cities of the central highlands, the most populated region, with those located in Petén are complicated and follow winding routes to avoid crossing over the mountains. In terms of air transportation, there are only two airports in Guatemala that are expressly authorized to receive foreign tourists: La Aurora in the nation’s capital and Mundo Maya close to Flores, in the vicinity of the archeological site of Tikal (although this airport only received 0.5% of all foreign tourists that arrived in the country via air in 2014; INGUAT, 2014). Marine transportation for tourism is limited to a couple of ports for the arrival of cruise ships: one in the Pacific (Puerto Quetzal) and the other, Santo Tomás de Castilla, located in Amatique Bay off the Gulf of Honduras (Sánchez-Crispín et al., op. cit.). In general terms, land connections between Guatemala, Mexico and El Salvador are adequate, but deficient when it comes to Belize and Honduras. By air, the country is connected to all seven countries on the Central American isthmus, as well as to Mexico and the United States. However, there are no direct flights to or from Europe or Asia, both important markets in terms of international tourism.

Regarding the promotion of tourism by national organizations in Guatemala, information available online (www.inguat.gob.gt) indicates that the government emphasizes the existence of resources (both natural and cultural) over infrastructure. In this context, the three most widely promoted facets online are: Mayan heritage, Guatemalan culture and kayaking on Lake Atitlán (Pitt et al., 2008). This aspect of promoting tourism in Guatemala has a considerable impact on administration and marketing in terms of leveraging the country’s resource potential, especially when it comes to encouraging new forms of tourism that have gained popularity in the international market, such as bird and plant watching, hiking, volcano climbing, kayaking and agritourism. Even so, only a handful of Central America’s major tourist attractions are located within Guatemalan territory: Antigua (which neighbors on different natural and cultural resources), Tikal (the most visited archeological site in the country) and the lakeside towns of Lake Atitlán, known for their living culture and unique location on the banks of the fresh water lake surrounded by volcanoes (Rascón, 2010; Sánchez-Crispín et al., op. cit., and Sánchez-Crispín and Propin, 2010).

Natural Protected Areas and Tourism in Guatemala

The territories that today are classified as protected areas in Guatemala have a long history, one associated with the knowledge of the Mayan people and their management of the natural environment. The official designation of these protected areas dates back to the mid-twentieth century; however, the formal introduction of tourism to these areas as a notable economic activity is much more recent. The different classifications assigned to these territories were not intended originally to promote visitation; nevertheless, over the years, and as the practice of tourism has evolved around the globe, seemingly guided by a cry to respect the natural environment, many of Guatemala’s protected areas have benefited by becoming sites of preference for the promotion of tourism.

Included in the very first declarations of protection made by the Guatemalan government back in 1955 were Tikal, Grutas de Lanquín (Lanquín Caves), Río Dulce (Sweet River) and the Lake Atitlán watershed, as well as the permanent ban area of San Pedro Volcano, located on the southwestern edge of the lake (CONAP, 2000, 2015; Elbers, 2011). Guatemala’s Protected Areas Act was issued in 1989 and, that same year, the National Council for Protected Areas (CONAP for its acronym in Spanish) was established, which now also incorporates and registers municipal and private reserves. Today, there are 334 protected areas (many of which are private) spanning more than 7.5 million acres or 31% of the national territory (CONAP, 2016); however, only 51 of these have the infrastructure and services required for tourism, including what was originally known as Atitlán National Park, which was added to the Guatemalan Protected Areas System by official decree on May 26, 1955.

In 1993, Lake Atitlán was recategorized as the “Lake Atitlán Watershed Multiple-Use Reserve” (RUMCLA for its acronym in Spanish) and in 2000, by private initiative, the Lake Atitlán Watershed Multiple-Use Protected Area Master Plan was created (USAID, 2004). This protected area contains segments occupied by ancient human settlements, the majority of which have small populations, but that together totaling nearly 440,000 inhabitants, as well as traditional and commercial agricultural lands and private reserves. In total, RUMCLA spans an area of over 300,000 acres, its boundaries forming a rectangle from north to south with Lake Atitlán at the center. While the borders of the watershed extend into the departments of Chimaltenango, Quiché, Suchitepequez and Totonicapan, the majority is situated within Sololá Department (CONAP, 2016). The lakeshore contains RAMSAR-type wetlands that cover a surface area of 31,000 acres (Ibid.); however, despite the wealth of resources contained within RUMCLA’s official perimeter, it was not until 2015 that the Guatemalan government intentionally began to encourage tourism to the lake through a stimulus program (Programa Impulso) that provided support to small business ventures proposed by the local population.

The promotion of tourism in Guatemala focuses on the country’s ethnic and cultural wealth. The Maya, the largest indigenous group in the country, are not a homogeneous people, but that is how they are perceived and, thus, promoted. At Lake Atitlán, tourists can interact with the natives, which leads them to believe that they have had an authentic experience, when, in reality, the lakeside inhabitants dress in their traditional clothing only to impress the tourists, having stopped using it as everyday attire many years ago, especially in the case of the men. (While the government has opted to promote the Mayan culture in the international market as the primary advantage of visiting Guatemala (Heart of the Mayan World), other national cultures do exist, such as that of the Caribbean.) Special attention is given to the Mayan female figure for this reason—Mayan men seldom appear in official tourism advertising. The economic and social backwardness of these lakeside towns is believed to be authentic and, as such, desirable to tourists, especially foreigners and people of high purchasing power.

The Mundo Maya (Mayan World) organization was founded in 1992 (with participation by the governments of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador) for the purpose of supporting cultural and environmental tourism in the Mayan region. The organization’s promotional activities aim to present the Maya to the Western traveler in an appealing light, always wearing typical dress, living in traditional housing and working as artisans; the same strategy is used by the Guatemalan Institute of Tourism (INGUAT, 2007). Mundo Maya directs its efforts at promoting the areas with specific resources that are attractive to tourists and, as such, these become more important than the Mayan population itself (Ibid.). In contrast, some of the most important sites for the Maya have been overlooked by this tourist propaganda and have been excluded from tourist maps.

Geographical Aspects of Lake Atitlán and Their Relationship to Tourism

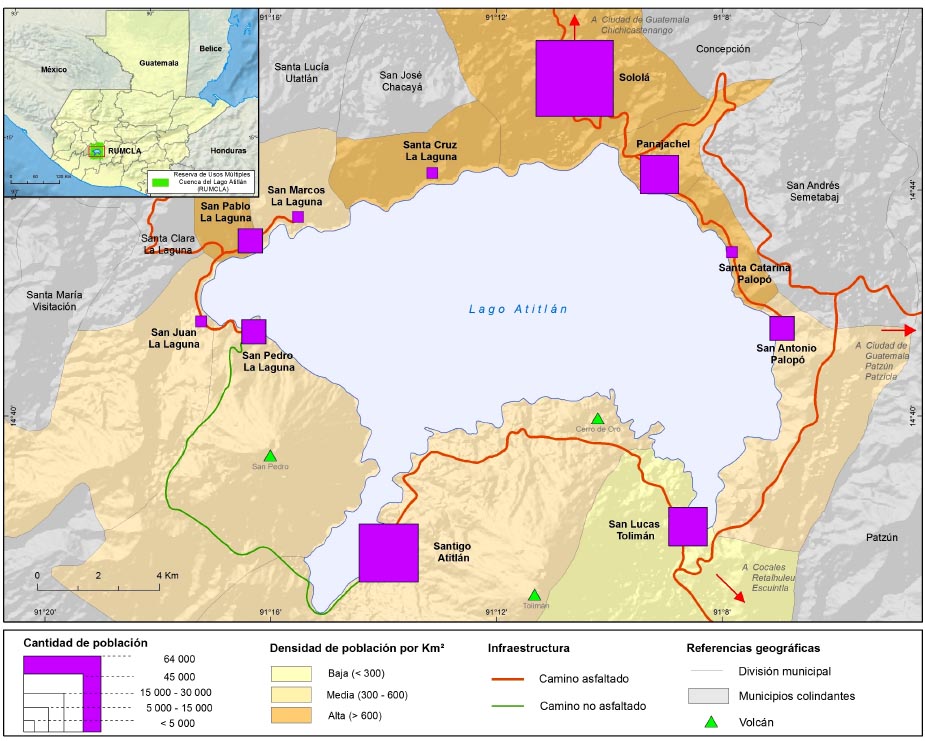

Lake Atitlán spans an area of approximately 125 km2 (48 mi2) and is bordered by the tributaries of Motagua River to the north, Madre Vieja River to the east and Nahualate River to the south and south-west (UVG, 2002, figure 1). It is oval in shape with axes measuring 18.9 km (11.7 mi) from north-west to south-east and 17.6 km (10.9 mi) from south to north-northwest (Instituto Geográfico Nacional, 2004). Along the lake’s southern edge lie the bays of Santiago Atitlán and San Lucas Tolimán, home to towns of the same name (Castañeda, 2011).

The lake is contained within an endorheic watershed encompassing a surface area of 540 km2 (208.5 mi2) and occupying a large caldera with sharp escarpments along the northern and eastern flanks and delimited to the south and south-west by four protruding volcanic structures that are part of the Sierra Madre mountain range (Hernández et al., 2010; UNEP-CATHALAC, 2011). Three of these volcanoes have an altitude of over 3,000 m (9,800 ft): Atitlán or Xkanuul (3,535 m/11,598 ft above sea level), Tolimán or Pra’l (3,158 m/10,361 ft) and San Pedro or Chuchuk (3,020 m/9,908 ft) (Ochoa, 1998); the fourth volcano, Cerro de Oro, is smaller (1,650 m/5,413 ft) and geologically younger than the others (Cattelan, 2008; Viñals, 2008). The existence of these geomorphic structures confers a uniqueness on the lake that is well recognized by travelers: an aesthetic lake scene framed by volcanoes. Given the relative isolation of the volcanoes from the watershed, they have been classified as islands of evolution, which function as endemic areas for plant and animal species (Jones, 2012), providing a place of refuge for scientifically valuable animal and plant species, such as the horned guan, trogons and spider monkeys (Mancilla, 2008).

Figure 1. Lake Atitlán: Population and population density in 2013

Elaborado con base en: INE, 2013 y trabajo de campo 2013-2015

Lava flows, lahar and tuffs are frequent occurrences from the volcanic quaternary (Barillas, 2012). Given the geological formation of the watershed, regional seismicity levels and rainfall patterns associated with cyclones and excessive rainfall, there is a history of landslides in the area, particularly in the northeastern sector and in the foothills of Tolimán Volcano, some of which have had a visible impact on the town of Panajachel situated on the right bank of the river of the same name (Ibid.). This diversity in terms of physical geography has afforded the lake a significant number of natural resources; however, tourism today has little to do with the designation of the lake as a protected area more than 60 years ago.

The endorheic nature of the watershed facilitates the concentration of sediment, debris and contaminants within the lake itself. The issue of the lake’s contamination has been made public in recent years due to rising levels of contamination from rapid phytoplankton growth (UNEP-CATHALAC, 2011). Furthermore, the disposal of wastewater from both domestic and agricultural use in the highland areas is a significant problem when it comes to maintaining the lake in clean conditions, which, in turn, is fundamental to growing rates of tourism in all of the lakeside towns and municipalities, home to more than 200,000 inhabitants. Moreover, given the sharp incline, the caldera’s walls are subject to mass wasting due to extreme rains, such as those produced by hurricane Stan in 2005, which resulted in landslides that destroyed crops, homes and infrastructure. In 2011, the lake’s water level rose by more than one meter (3.3 ft), flooding homes at different points along the lake’s banks, the results of which were still visible in early 2015. The diversity of vegetation along the banks and slopes of the caldera is put to use in a variety of ways, including the construction of homes, hotels and piers, the promotion of tourism, described as natural, fresh or mild, and the production of handicrafts.

Nevertheless, Lake Atitlán is suffering from severe environmental stress. Based on recent satellite images, approximately 40% of the lake’s surface is covered by algae, added to the undeniable presence of cyanobacteria as a result of the disposal of wastewaters from domestic and agricultural use (Ibid.). Moreover, the continuous introduction of aquatic nuisance species into the lake has greatly affected the living conditions of native species, and the presence of phosphates and nitrates is much higher than it was decades ago. This situation should not be happening within a protected area or, at the very least, actions should be taken to counteract it.

The climate in the watershed along the lake’s banks is Cwb (subtropical highland) and Aw (tropical savanna) in the lake itself (McBryde, 1969). This means the existence of mild climates, such as in Sololá, and subtropical climates, such as in Panajachel, in very close proximity to each other, in this case due to the difference in altitude. This, in turn, means different environments for tourism that favor a diversity of recreational activities, separated by relatively short distances. Annual rainfall around the lake is approximately 1,000 mm (39 in.). Panajachel, for example, registers a little over 1,400 mm (55 in.) a year, whereas the south and southwestern sectors, home to the principal volcanoes, receive between 2,000 and 3,500 mm (79-138 in.) annually (Barillas, op. cit.). Rainfall usually occurs in summer (locally referred to as winter, as in other Central American countries), which results in low precipitation between October and April, thus attracting a significant number of tourists from the Northern Hemisphere where harsh winter climates abound during exactly those months.

As previously indicated, the majority of RUMCLA is situated within Sololá Department in southwest Guatemala (UVG, 2003), one of the poorest and most marginalized areas of the national territory, forming part of what is known as the poverty belt (which includes regions in north, northwest and southwest Guatemala) (Alwang et al., 2005). Eleven of the department’s twenty municipalities are located along the banks of Lake Atitlán, along with eleven towns (Castañeda, 2011; Morán, 1969). The most important city in the area is Sololá, the department capital, with approximately 30,000 inhabitants, located in the caldera’s highlands more than 600 m (2,000 ft) above the other lakeside settlements. Sololá’s urban functions outline an area of influence that includes all of the surrounding towns; however, daily life in Sololá is not closely related to what is happening at the lake or in the other ten towns located down in the caldera’s interior.

From Sololá, moving in a clockwise direction, the other ten lakeside towns are: Panajachel, Santa Catarina Palopó, San Antonio Palopó, San Lucas Tolimán, Santiago Atitlán, San Pedro la Laguna, San Juan la Laguna, San Pablo la Laguna, San Marcos la Laguna and Santa Cruz la Laguna (Figure 1). There are other villages located in close proximity to the lake, but higher up, such as San Jorge la Laguna, whose relationship with the aforementioned communities is less intense. Each of these towns has a pier, albeit of varying size, for the arrival and departure of boats and other modes of lake transportation, provided to both tourists (national and foreign) and the local population. Panajachel serves as the hub for local transportation (land and lake), from where one can catch either cabotage or direct routes to the other lakeside towns. Of particular importance are the routes connecting Santiago Atitlán and San Pedro la Laguna, for this reason, Panajachel has become a necessary point of transit for tourists visiting the lake or wishing to overnight at one the various waterfront towns.

From the city of Sololá, the distance by land to the different municipal capitals varies greatly. There is frequent travel to and from Panajachel at a distance of only 9 km (5.5 mi), (although with a difference in altitude of approximately 600 m (2,000 ft) on a two-lane highway that tends to wash out frequently during the rainy season). Southeast of Panajachel, the towns of Santa Catarina Palopó and San Antonio Palopó, at a distance of 13 km and 17 km (8 and 10.5 mi), respectively, are connected to Sololá by a narrow, coastal road. In the same direction, but at a distance of 27 km (17 mi) from the department capital, along a road that does not follow the lake’s shoreline, lies San Lucas Tolimán. The two towns situated at the greatest distance from Sololá are San Pedro la Laguna (85 km/53 mi) and Santiago Atitlán (62 km/38.5 mi), given that the area’s topography does not allow for a direct route of transportation (Figure 1). San Marcos la Laguna, San Pablo la Laguna and San Juan la Laguna are located along the lake’s northwest flank at a distance of 23 km, 25 km and 26 km (14, 15.5 and 16 mi), respectively, from Sololá by dirt road. Finally, the closest community to the department capital is Santa Cruz la Laguna at a distance of only 7 km (4.5 mi).

In terms of population, the lakeside towns are relatively small, but the rural population density is quite considerable, distributed among localities called settlements, villages, farms and hamlets, the majority of which are situated in the foothills and terraces above the banks of the lake and associated rivers (Barillas, 2012). The centers with the largest populations, Panajachel (10,000 inhabitants), San Lucas Tolimán (13,000) and Santiago Atitlán (approximately 30,000), are situated directly on the lake. The geographical dispersion of the population is best described in the case of the municipality of Santiago Atitlán, with a total population size of approximately 45,000 inhabitants distributed among 92 settlements that represent almost 45% of the total number of lakeside inhabitants. When subtracting the case of the municipal capital, the population of these settlements averages less than 125 people per village (Instituto Geográfico Nacional, op. cit.). With the exception of one, all of the municipalities surrounding Lake Atitlán have a majority indigenous population. In fact, in Santa Catarina Palopó, San Pedro la Laguna, San Pablo la Laguna, San Marcos la Laguna and Santa Cruz la Laguna, more than 98% of the population is indigenous, speaking kaqchikel or tz’utujil as their primary language (INE, 2013). The only lakeside municipality with a smaller indigenous population is Panajachel, totaling 65% (Table 1).

In terms of existing cultural resources in the towns situated along the banks of Lake Atitlán, it is important to highlight the idea of exoticism as a fundamental ingredient in the promotion of ethnic tourism, a new form of tourism that is gaining ground around the world based on the expectations and stereotypes held by tourists regarding a specific place, who travel with the express purpose of seeing something authentic (Gloster, 2012). This so-called authenticity can be related to the rural environment, to primitiveness (such as cave art), to purity, originality or to what is yet uncontaminated; on the other hand, authenticity can also refer to how a tourist perceives the experience of being in a certain place. Exclusivity as a path to authenticity is now promoted around the globe in an attempt to attract international travelers (Ibid.). Given that the majority of tourists today come from Western cultures, their concepts, expectations and values are anchored in that culture, thus setting the context by which international travelers evaluate a cultural landscape, projecting onto it their beliefs, preferences and expectations. It is important to add, furthermore, that an asymmetrical relationship exists between the inhabitants of a poor country (such as Guatemala) and visitors from rich nations (such as the United States, Canada, Western European contries) based on superiority (of economic resources, purchasing power, accumulation of material goods) and marginalization (geographic, social and economic). This relationship results in a tendency to perceive the local population as living museums to promote tourism, which only perpetuates the stereotype of indigenous populations in areas such as those surrounding Lake Atitlán.

Table 1. Municipalities of Sololá Department Along Lake Atitlán: Surface area, number of inhabitants, number of communities and dominant language in 2012

|

Municipality |

Surface Area (km2) |

Population |

Number of Communities |

Indigenous Population (%) |

Dominant Language |

|

Sololá (municipal capital) |

94 |

64 000 |

26 |

90 |

Kaqchikel |

|

Panajachel |

22 |

17 361 |

17 |

65 |

Kaqchikel |

|

Santa Catarina Palopó |

8 |

5 675 |

6 |

98 |

Kaqchikel |

|

San Antonio Palopó |

34 |

13 274 |

29 |

92 |

Kaqchikel |

|

San Lucas Tolimán |

116 |

30 189 |

18 |

85 |

Kaqchikel y tz’utujil |

|

Santiago Atitlán |

136 |

45 767 |

92 |

95 |

Tz’utujil |

|

San Pedro la Laguna |

24 |

11 358 |

4 |

98 |

Tz’utujil |

|

San Juan la Laguna |

36 |

11 047 |

7 |

90 |

Tz’utujil |

|

San Pablo la Laguna |

12 |

7 464 |

1 |

99 |

Tz’utujil |

|

San Marcos la Laguna |

12 |

4 320 |

2 |

98 |

Kaqchikel |

|

Santa Cruz la Laguna |

12 |

7 330 |

7 |

99 |

Kaqchikel |

|

506 |

217 785 |

209 |

Source: INE, 2013. Note: Sololá Department has other municipalities that are not located along the banks of Lake Atitlán.

Lake Atitlán is one of the most important tourist sites in Guatemala. As early as the mid-twentieth century, it was identified as an easily accessible world-class tourist destination, along with Antigua, Chichicastenango, Río Dulce, the archeological site of Quiriguá and the Chiquimulilla canal (Del Valle, 1956). The lake beaches at Panajachel, San Lucas Tolimán, Santa Cruz la Laguna, San Pablo la Laguna, San Marcos la Laguna and San Juan la Laguna were also mentioned as sites of interest for tourism (Ibid.), as were the indigenous centers of San Antonio Palopó, San Pedro la Laguna, Santa Cruz la Laguna and Santiago Atitlán and the natural resources of Atitlán, San Lucas (or Tolimán), Cerro de Oro and San Pedro volcanoes. Today, all of these sites have entered the booming tourism dynamic, especially in terms of attracting foreign tourists.

According to Del Valle (Ibid.), seventy-some years ago, the Jacobsthal Project was intended to prepare Panajachel to be a first-class tourist center on Lake Atitlán. The plan was to improve land routes to the area and to open air travel. Similarly, the proposal included expanding accommodation offerings, redesigning the urban layout and alleviating the consequences of the frequent flooding of Panajachel river. Other towns were also included in the project: Santa Catarina Palopó, San Juan la Laguna and San Pedro la Laguna were considered first-rate textile production sites; San Pablo la Laguna was recognized for its beautiful lake beaches and production of fishing gear and tackle; San Marcos la Laguna was renowned for Cuicujil and Chuicomebal beaches; and Santiago Atitlán, the most populated and long-standing of the lakeside towns, for the production of textiles and the chance to travel around the lake to San Pedro and Cerro de Oro volcanoes (Ibid.). Today, 50 years later, these towns have found their place in niche opportunities, such as rural tourism, agritourism and adventure tourism.

An aspect of interest to contemporary tourism in the towns surrounding Lake Atitlán are the traditional markets. The most important, open only on Fridays, is the market in Santiago Atitlán, which offers a variety of everyday products and a considerable number of artisanal goods (textiles, wooden images, naïve art, etc.). The existence of Santiago Atitlán was mentioned in the 16th-century Relaciones Geográficas de Guatemala (Geographical Relations of Guatemala), written in 1585 by Francisco de Villacastín and accompanied by a map of the lake representing the most important geomorphological characteristics and some of the towns that today still surround the lake, including Santa Cruz, San Pablo and San Pedro la Laguna (Acuña, 1982). Santiago Atitlán also appears on the map made by Cortés and Larraz in the 1700s, along with Sololá, San Pedro la Laguna and Panajachel as 18th-century curacies (Bornholt, 2007). This denotes the antiquity of some of the lakeside settlements and the possible existence of indigenous markets more than three centuries ago. In addition to Santiago Atitlán, only Sololá (Tuesdays and Thursdays), Panajachel (Sundays; in addition to the artisanal shops open every day along Santander street, the main road through town) and San Lucas Tolimán (Tuesdays and Sundays) have markets of interest to tourists.

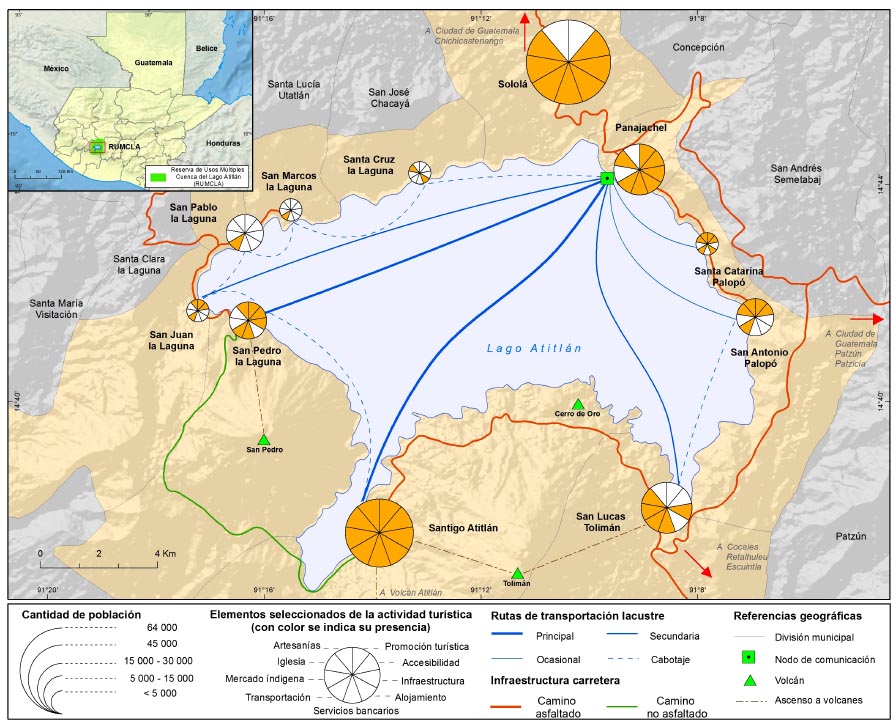

Top Tourist Sites on the Banks of Lake Atitlán

Based on several trips to the region between 2013 and 2015, we created a map showing the different attributes of each of the lakeside communities with some sort of importance to tourism (Figure 2). Nine attributes were chosen that directly influence the capacity of each town to participate in the constantly growing and increasingly competitive tourist industry at Lake Atitlán. By organizing the information on tourism in this part of Guatemala in this way, we are better able to explain which settlements are relevant in terms of tourism.

Figure 2. Lake Atitlán: Aspects of the lakeside towns of relevance to tourism

Elaborado con base en: Segeplan, 2015 y trabajo de campo 2013-2015

Panajachel. The point of entry to the lake, with a population of approximately 10,000 inhabitants. The road leading out from the city of Sololá reaches Panajachel first, the main port on the lake. It is situated in a position of vulnerability on the right bank of Panajachel River, but directly on the lake, which facilitates travel to the other lakeside settlements, including those accessible by land. Panajachel offers both first-rate and bargain accommodations as well as banks, ATMs and a considerable number of restaurants, bars and nightclubs. Panajachel’s reputation as a tourist destination soared during the 1970’s, when many Americans took refuge in this part of Guatemala to avoid being sent to the Vietnam War (the same was the case for San Pedro la Laguna). There is a marked difference between the town’s original center (where today one can find the market, the main square and San Francisco de Asis church) and Principal and Santander streets, catering mainly to international tourists, where one will find the majority of businesses and tourist services. It is from here that one can book excursions and trips not only to the different lakeside towns, but also to different parts of Guatemala (Chichicastenango and Antigua), Central America (Honduras, Belize, Costa Rica) and Mexico (Chiapas, Oaxaca, Yucatan Peninsula). Panajachel is, without a doubt, the tourist hub at Lake Atitlán, but while the Amigos del Lago de Atitlán (Friends of Lake Atitlán) organization is headquartered here and there are many private reserves, such as the Atitlán Reserve complete with butterfly garden, during our field visits, we were unable to detect that tourism in the area is associated with the promotion of RUMCLA.

Santiago Atitlán. The oldest and most populated of the ten lakeside towns. The church of Santiago Apóstol (Saint James the Apostle), constructed on the foundations of a Mayan pyramid (Szybist, 2004), is one of the most important local resources in terms of tourism, along with the main square and neighboring market. The pier is essential for communication with the other lakeside settlements, in particular with Panajachel, to which both cabotage and direct or express routes are offered. The road that connects the pier to the center of Santiago Atitlán is home to a large number of small businesses that cater to foreign tourists. Of particular interest are those that offer locally-produced handicrafts, made of wood, woven or painted, as well as naïve art that illustrates quotidian life on the lake. The existence of the Maximón house of worship makes Santiago Atitlán a special place in Guatemala. Maximón is the result of syncretism of the Mayan and Spanish cultures and is unique in that he is an evil deity. Many visitors to Santiago Atitlán head directly to visit his shrine. Furthermore, Santiago Atitlán is known both nationally and internationally for its production of handicrafts, a wide variety of which are offered for sale to tourists on Fridays, the day of the public market. Santiago Atitlán offers a variety of hotel categories as well as banks, restaurants and transportation to other areas of the municipality or to nearby towns. While Santiago Atitlán is a definite destination of preference on the lake, its tourist activity is not explicitly tied to the existence of the protected area.

San Pedro la Laguna. Situated on the western bank of Lake Atitlan, has a population of less than 10,000 inhabitants. For more than 40 years, San Pedro la Laguna has been a destination of preference on the lake, having been chosen as a place of refuge by young hippies fleeing from the draft during the Vietnam War. This lakeside town is known for its nightlife, including the best bars and nightclubs. In terms of natural resources, San Pedro la Laguna offers beaches, overlooks and the chance to hike San Pedro Volcano. Additionally, visitors can go fishing, sailing, water skiing, etc., in close proximity to town. In terms of cultural resources, there is the production of handicrafts, although not to the same scale or quality as some of the other lakeside towns, as well as the main square and recently constructed San Pedro (Saint Peter’s) church, built to replace the original church that was destroyed (Ibid.). In recent years, different Christian churches have been erected around town in response to San Pedro’s permissive environment. These churches offer baptismal services in the lake’s waters to both locals and foreigners, managed as part of the local tourist offering. San Pedro la Laguna has several options of hotel and different tourist services such as travel planning to the lake and beyond. It is a primary destination of the routes that cross the lake, but, while it is located within the natural reserve in question, there is no evidence that the reserve’s existence regulates or promotes tourism in this town.

Santa Catarina and San Antonio Palopó. These two towns are connected to Panajachel by both land and water and both are visited frequently by tourists. Of particular interest is the predominately kaqchikel-speaking population. The churches of Santa Catarina and San Antonio, dedicated to Saint Catherine and Saint Anthony of Padua, respectively, are unique in that they combine elements of both the indigenous and Spanish cultures and, in and of themselves, are first-rate cultural resources. The production of handicrafts, especially textiles, is distinguishable for their use of blues in the production of huipiles (traditional garments) and other clothing items. Ceramic workshops are popular in San Antonio Palopó and agritourism trips are offered to onion farms located on the surrounding terraces. The short distance of these towns from Panajachel allows tourists to visit for a few hours during the day without the need to spend the night; however, one of the most exclusive hotels in the country, Casa Palopó, is located just south of Santa Catarina, and has been described as one of the world’s best small hotels. Casa Palopó operates as an economic enclave in this part of the lake, catering to the needs of an international market with high purchasing power. The southeast section of the coastal road from Panajachel ends in San Antonio Palopó.

San Juan la Laguna. Neighboring San Pedro la Laguna, this small town lies on the lake’s western shore. It offers beaches, overlooks of the lake and nature trails along the roads that connect it to the other settlements. Of particular interest are local handicrafts made from natural materials and designed with recognizable patterns in pastel color tones. Additionally, San Juan la Laguna offers community-based tourism ventures, sustainable tourism and agritourism. However, the size of the town and distance from Panajachel, the point of entry to the lake, partly explain why tourism has not grown much in San Juan la Laguna. This town is noteworthy for its women-owned businesses, originating in the 1970’s, which today promote tourism to vegetable gardens and textile workshops (Rascón, 2011).

Other towns. Tourism in the remaining lakeside settlements is on the rise; efforts are being made to give them an advantage in a very competitive market. For example, San Marcos la Laguna has focused on offering tourism associated with yoga, meditation and spa retreats, taking advantage of local thermal waters. Bird watching is also big here, thus leveraging the lake as a place of relaxation. Santa Cruz la Laguna offers a church (dedicated to Saint Helen of the Cross) and main square that are of interest to foreign visitors. In both cases, however, the vertical distance between the pier and town center is an obstacle for the arrival of tourists, which is compensated with special lake tours or tours to nearby volcanoes. Of all the lakeside towns, San Lucas Tolimán receives the least number of tourists considering its demographics. While it represents a point of departure for hiking the area’s volcanoes, it has fewer cultural resources than the other lakeside towns. Moreover, San Lucas Tolimán is connected only to Panajachel and Santiago Atitlán by very rudimentary roads.

Conclusions

Lake Atitlán and the surrounding lakeside communities are of primary interest to the practice of tourism in Guatemala, due as much to foreign tourists as to nationals who visit the lake for a variety of recreational reasons. This part of Guatemalan territory offers a considerable diversity of natural and cultural resources, such as volcanoes, mild climates, subtropical vegetation and native flora and fauna; however, the primary element of the area’s physical geography that sustains tourism to the area is the lake itself, Lake Atitlán, regardless of its state of contamination, higher in some areas than others. The different ethnic groups that live along the lake’s banks are a solid foundation for the promotion of tourism in this part of Guatemala, especially those that speak kaqchikel and tz’utujil. Their culture, evidenced in the production of handicrafts, local foods, traditional dress, weekly markets and patron saint festivals, is a powerful attraction for these lakeside towns and, most importantly, for Santiago Atitlán, Santa Catarina, San Antonio Palopó and San Juan la Laguna.

Tourism to the lake starts in Panajachel, where tourists are received and then transferred to the different communities along the lake’s shore. It is a central place on Lake Atitlán given its supply of banks, services and transportation. Its hinterland extends well beyond the watershed itself, providing goods and services to relatively-distant towns, such as Chichicastenango and Antigua, both also very popular with tourists. Whether by land or by lake, Panajachel is the origin and destination of the main routes that cross the lake, used by both collective and private vessels for direct or cabotage transportation. While Santiago Atitlán is the oldest and most populated of the lakeside towns, its location on a sheltered bay far from the rest of the lake perimeter hinders it competing with Panajachel in terms of the provision of goods and services to tourists, mostly of international origin. Sololá, the department capital, remains on the margin of tourism dynamics in the area, due partly to its location 600 meters above the lake and partly to the road down, which is very difficult to transit, especially during the rainy season. As such, it only functions as a place of passage on the trip down to the water’s edge, the first stop being in Panajachel.

Generally, foreign tourists will visit the lake on a day tour and spend only a short amount of time in the different lakeside settlements included in their itinerary, such as Santiago Atitlán or San Antonio Palopó, which are easily accessed by boat from Panajachel. The boat trip itself is an added bonus to the experience of witnessing the views from the different lakeside towns of the caldera that houses the lake as well as the chance to appreciate the living culture in each of the settlements included in the tour, which often starts in Antigua, Guatemala, or in the nation’s capital. For the majority of visitors, Lake Atitlán is a place of admiration, observation and meditation, more so than for the practice of extreme sports.

The origin of tourism at the lake is predominately regional, from neighboring countries like El Salvador, Honduras and Costa Rica, although the influx of visitors from the United States, Canada and Mexico is also quite considerable. This means that tourism to the lake should be promoted first and foremost in North and Central America. To date, this promotion has focused on highlighting unique elements of the area’s geography, such as the lake’s image shown on the arrival platforms at La Aurora International Airport, in the nation’s capital, as an invitation to travel; or the encouragement among travelers arriving on cruise ships at Puerto Quetzal on Guatemala’s Pacific Coast to travel to the lake for the day, meaning a three-hour journey one way.

Despite the above, no connection was found between the existence of RUMCLA and the promotion of tourism in this part of Guatemala, not even in recent actions by the Guatemalan Institute of Tourism to promote visitation to the lake and lakeside towns in its proposed Altiplano Viviente (Living Altiplano) program (INGUAT, 2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank José Alberto Garibay Gómez, Álvaro Moisés Sánchez Mier (RIP), Rodrigo Pérez Toledo and Mario Ortega, at the time all students of the Institute of Geography of the School of Philosophy and Letters of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, for their participation in the field work at the lake between 2013 and 2015. In particular, we would like to recognize the automated cartography of Juan de Dios Páramo Gómez, who prepared the final version of the maps used in this investigation.

References

Acuña, R. (1982). Relaciones geográficas del siglo XVI: Guatemala [Geographical relationships of the 16th century: Guatemala]. Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas. National Autonomous University of Mexico. Mexico City, Mexico.

Alwang, J., Siegel, P., and Wooddall-Gainey, D. (2005). Spatial analysis of rural economic growth potential in Guatemala. The World Bank. Sustainable Development Working Paper 21. Washington, DC, United States.

Barillas, E. (2012). Historia y ocurrencia de los deslizamientos generados por lluvia en Guatemala, Centro América [History and occurrence of landslides generated by rainfall in Guatemala, Central America]. Fulbright Foundation. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Bornholt, J. (2007). Cuatro siglos de expresiones geográficas del istmo centroamericano. 1500-1900 [Four centuries of geographical expressions from the Central American Isthmus. 1500-1900]. Francisco Marroquín University. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Castañeda, C. (2011). Lago de Atitlán: sociedad y naturaleza en Guatemala [Lake Atitlán: Society and nature in Guatemala]. Territorio y región. Agua, drenajes y recursos naturales en Guatemala. Centro de Estudios Urbanos y Regionales. Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala City, Guatemala. pp. 195-231.

Cattelan, M. (2008). Atitlán. Xilbabá Publicaciones. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas. (2016). Memoria de Labores, 2015 [2015 Annual report]. Sistema Guatemalteco de Áreas Protegidas. Gobierno de Guatemala. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Del Valle, J. (1956). Guía sociogeográfica de Guatemala [Socio-geographical guide to Guatemala]. Talles de Tipografía Nacional. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Domínguez, M. (2012). Estructura territorial del turismo en el Parque Nacional Volcán de Pacaya, Guatemala. [Territorial structure of tourism at Pacaya Volcano National Park, Guatemala]. Master’s Thesis in Geography. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, National Autonomous University of Mexico. Mexico City, Mexico.

Elbers, J. (2011). Las áreas protegidas de América Latina: Situación actual y perspectivas para el futuro [Protected areas of Latin America: Current situation and future perspectives]. Quito, Ecuador, UICN. p. 227.

Gloster, M. (2012). La comercialización del turismo étnico en Guatemala y Marruecos [The commercialization of ethnic tourism in Guatemala and Morocco]. Scripps Senior Thesis. Paper 74. Claremont, CA, United States.

Hernández, B., Flores, Á., García, B., Clemente, A., Morán, M., Cherrington, E., Oyuela, M., Smith, O. and Guardia, J. (2010). Monitoreo satelital del Lago Atitlán, Guatemala [Satellite monitoring of Lake Atitlán, Guatemala]. Centro de Agua del Trópico Húmedo para América Latina y el Caribe. City of Knowledge, Panama.

Instituto Geográfico Nacional. (2004). Biogeografía de Santiago Atitlán [Biogeography of Santiago Atitlán]. Gobierno de Guatemala. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Instituto Guatemalteco de Turismo. (2007). Plan Estratégico de Dinamización Turística para el Lago de Atitlán [Strategic Plan for the Dynamization of Tourism for Lake Atitlán]. Instituto Guatemalteco de Turismo and Inter-American Development Bank. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Instituto Guatemalteco de Turismo. (2014). Boletín de Estadísticas de Turismo [Tourism statistics bulletin]. Instituto Guatemalteco de Turismo. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2013). Estadísticas económicas [Economic statistics]. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Jones, H. (2012). “Tres estudios de caso de ecoturismo basado en comunidades: Amistad-Bocas del Toro, Costa Rica; Volcanes de Atitlán, Guatemala; y Reserva Nacional de Pacaya-Samiria, Perú” [Three case studies of community-based ecotourism: Amistad-Bocas del Toro, Costa Rica; Atitlán Volcanos, Guatemala; and Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve, Peru]. Servicios de Ecosistemas en América Latina y el Caribe. The Nature Conservancy-USAID and the Alex Walker Foundation. Cartagena, Colombia. pp. 49-58

Luján, J. (2011). Atlas histórico de Guatemala [Historical atlas of Guatemala]. Academia de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Mancilla, E. (2008). Diagnóstico socioeconómico, potencialidades productivas y propuestas de inversión. Municipio de Santiago Atitlán, Sololá, Guatemala. [Socioeconomic analysis, production potentialities and investment proposals. Municipality of Santiago Atitlán, Sololá, Guatemala.] Vol. 12. Comercialización y producción de zucchini. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

McBryde, F. (1969). Geografía cultural e histórica del suroeste de Guatemala [Cultural and historical geography of south-west Guatemala]. Seminario de Integración Social Guatemalteca, 24. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Morán, S. (1969). Guía geográfica de los departamentos de Guatemala [Geographical guide to the departments of Guatemala]. Del Águila Editores. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Ochoa, C. (1998). Nuestra Geografía del lago Atitlán [Our geography of Lake Atitlán]. Casa de Estudios de los Pueblos del Lago Atitlán. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Pitt, L., Berthon, P., Nel, D. and Loria, K. (2008). Measuring tourism website communication out of Central America. Australia and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference Proceedings 2008. pp. 1-6.

Rascón, E. (2010). “Turismo rural-cultural. El caso del municipio de San Juan la Laguna, Guatemala” [Cultural rural tourism: The case of San Juan la Laguna, Guatemala]. TUR y DES. Revista de Investigación en Turismo y Desarrollo Local, 3-7. Red Académica Iberoamericana Global-Local. University of Malaga. Malaga, Spain. pp. 1-14

Rascón, E. (2011). “Crecimiento y características del turismo en Guatemala: el caso de San Juan la Laguna, Sololá” [Growth and characteristics of tourism in Guatemala: The case of San Juan la Laguna, Sololá]. ¿Es posible otro turismo? Vol. II. Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales. Costa Rica location. San Jose, Costa Rica. pp. 306-338

Sánchez-Crispín, A., Mollinedo, G. and Propin, E. (2012). Estructura territorial del turismo en Guatemala [Territorial structure of tourism in Guatemala]. Investigaciones Geográficas, 78, 104-121

Sánchez-Crispín A. and Propin, E. (2010). Tipología de los núcleos turísticos primarios de América Central [Typology of Central America’s principal tourist sites]. Cuadernos de Turismo, 25, 165-184.

Szybist, R. (2004). The Lake Atitlan Reference Guide. Adventures in Education Inc. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Teer, J., Gramann, J., Jones, J. and Sirakaya, E. (1999). Study of ecotourism potential in Tikal, Lake Atitlan and Antigua, Guatemala. Texas A&M University. College Station, TX, United States.

UNEP-CATHALAC. (2011). Latin America and the Caribbean Atlas of Our Changing Environment. Centro del Agua del Trópico Húmedo de América Latina y el Caribe. United Nations Environmental Program. Panama, Panama.

USAID. (2004). Plan de Manejo “Reserva Natural Privada Santo Tomás Pachuj” [Santo Tomás Pachuj Private Natural Reserve Management Plan]. USAID and the Nature Conservancy. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

Viñals, J. (2008). Guatemala. Tierra de volcanes [Guatemala: Land of volcanoes]. Empresa Eléctrica de Guatemala. Guatemala City, Guatemala.

1 Lead Investigator. Institute of Geography, UNAM. Mexico City, Mexico. Email: asc@igg.unam.mx

2 Lead Investigator. Institute of Geography, UNAM. Mexico City, Mexico. Email: propinfrejomil@yahoo.com

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional.