Revista Geográfica

ISSN: 1011-484X

Número Especial I Semestre 2017

Doi: dx.doi.org/10.15359/rgac.58-2.5

Páginas de la 137 a la 183 del documento impreso

Recibido: 7/8/2016 • Aceptado: 10/11/2016

|

Revista Geográfica ISSN: 1011-484X Número Especial I Semestre 2017 Doi: dx.doi.org/10.15359/rgac.58-2.5 Páginas de la 137 a la 183 del documento impreso Recibido: 7/8/2016 • Aceptado: 10/11/2016 |

Tourism and territory in natural protected areas. Santa Rosa National Park: from national monument to conservation of the tropical dry forest. Guanacaste Conservation Area, Costa Rica

Turismo y territorio en áreas naturales protegidas, Parque Nacional Santa Rosa: del monumento nacional a la conservación del bosque tropical seco, Área de Conservación Guanacaste, Costa Rica

Lilliam Quirós-Arias1

National University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

ABSTRACT

Ever since the 1980s, conservation-related tourism has been particularly important in Costa Rica. The interest in enjoying and being part of nature brought a significant change to how tourism is practiced. The country hosts a great wealth of natural and cultural resources, as well as rural landscapes characterized by protected areas and surrounded by natural landscapes and local communities. This document reviews the experience of Santa Rosa National Park, located in the Guanacaste Conservation Area (ACG)—an area with emerging tourism development and natural attractions as its main resource. The participation and integration of local communities are part of recent concerns. Our methodology includes a review of secondary information and first-person interviews with townspeople. Moreover, information was gathered on-site through different visits to the area of study. The ACG is one of the protected areas that hosts important resources for research; however, increasing conservation in neighboring areas and incorporating the local community still represents a challenge.

Keywords: tourism, natural protected areas, conservation, land management, Costa Rica

RESUMEN

El turismo ligado a la conservación adquiere una importancia particular en Costa Rica a partir de los años ochenta; el interés por disfrutar y participar de la naturaleza marca un cambio en la práctica del turismo. El país alberga una gran riqueza de recursos naturales y culturales; así como paisajes rurales, caracterizados por áreas naturales protegidas, éstas rodeadas por agropaisajes y comunidades locales. En el presente estudio, se revisa la experiencia del Parque Nacional Santa Rosa, ubicado en el Área de Conservación Guanacaste (ACG), donde el desarrollo turístico es incipiente, con atractivos de tipo natural como núcleo de la actividad. La participación de las comunidades locales y su integración, forman parte de las preocupaciones recientes. La metodología incluyó revisión de la información secundaria y, del mismo modo, se realizan entrevistas a los pobladores; además, se recolecta información de campo a través de repetidas visitas al área de interés. El ACG es una de las áreas protegidas que alberga importantes recursos para la investigación, siendo todavía un desafío aumentar la conservación de las áreas adyacentes incorporando la comunidad local2.

Palabras clave: turismo, áreas naturales protegidas, conservación, ordenamiento territorial, Costa Rica.

1. Introduction

Since the early years of the Republic, Costa Rica has demonstrated a concern for the environment and the values that go hand in hand through the declaration of regulations and decrees, which were later increased in the century that followed during a period in which the country witnessed the massive destruction of its natural resources and the devastation of large forest areas and, with it, the biodiversity they contained. According to Costa Rica’s Forest Financing Fund (FONAFIFO, for its acronym in Spanish), from 1800 to 1950, forest coverage, once representing 91.3% of the national territory, was reduced to 64% and, from 1950 to 1987, dropped even lower to a mere 25%. Today, the classification of natural protected areas into a series of categories is a way to ensure their protection. From the creation of the very first protected area in 1963, the country has experienced a rise in the incorporation of areas into its natural heritage. According to the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC, for its acronym in Spanish) (2011), there are 170 protected wilderness areas in Costa Rica, representing 26.28% (3,313,367 acres) of national continental territory and 17.19% of national marine territory. Thirty-seven official biological corridors encompass 34% of the country’s land area, in addition to 11 RAMSAR sites, 3 biosphere reserves and 3 World Heritage Sites, all of which are important for the conservation of biodiversity and provide a wide range of ecosystems and economic services especially in terms of tourism, hydroelectric power and basic irrigation for agriculture. On this subject, Furst, Moreno, García and Zamora (2004) write that in addition to ecological services, these protected areas provide another type of service, typified as economic, social and institutional, in that their intelligent management generates diverse socioeconomic activities in the surrounding areas, which, in turn, contribute to the socioeconomic development of the country, above all at the local level (p.8).

Tourism to the country began to grow in the 1970s, sustained by the country’s chief resource: its natural protected areas and private conservation areas. The concept of ecotourism was promoted at an international level and the first experiences proved to be successful, attracting tourists from every corner of the globe motivated to practice a more environmentally responsible form of tourism. In the years that followed, data indicates that six of every ten tourists who enter the country visit one or more of the natural protected areas. The emphasis placed on developing tourism based on the country’s wealth of natural and cultural resources has transformed these areas into highly esteemed spaces at both the national and international levels. Based on Sánchez and Propin’s typology of the primary tourist centers in Central America (2010), 21 of Costa Rica’s 25 primary tourist centers are popular because of their natural resources.

According to Costa Rica’s Tourism Board (ICT, for its acronym in Spanish) (2013), 58.1% of all foreign tourists visit at least one protected area; 72.3% of visitors claim their reason for travel is for vacation, relaxation, recreation or pleasure purposes; 50.1% plan their trip independently in their home country; and 69.6% come to Costa Rica because friends or family recommended it. On average, tourists remain in the country for 11.4 days and spend $1,302.80 per person. The economic importance of tourism for the country is significant. The ICT’s Yearbook of Tourism Statistics for 2013 indicates that 2,427,941 tourists entered the country that year, spending a total of $2.3 billion. This places tourism on the top of the list in terms of income generators, ousting agricultural products such as coffee, bananas and pineapple (traditionally the first two have been the highest income generators in the country). That same year, tourism directly contributed 4.5% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

The relationship between tourism and conservation is evident given that the majority of tourist services are located outside of the greater metropolitan area. According to the ICT, tourism in the country is related first and foremost to the sun and sand, flora and fauna, nature hikes and volcanoes, all of which require a visit to one or more of the country’s natural protected areas or private conservation areas.

2. Conservation, Tourism and Territory

The creation of natural protected areas in Latin America is based on the idea that man is a destroyer of nature and that natural areas should be untouchable given their vulnerability to change. Areas of ecological wealth are protected in order to safeguard the wildlife they contain, under the belief that only empty spaces can be conserved (Diegues, 2000). This approach, which was first introduced in the United States with the creation of National Yellowstone Park (1872), was soon adopted by countries in Latin American, resulting in a sharp rise in the number of natural protected areas, national parks and reserves as a strategy for conserving nature. Soon, however, these areas began to compete with agricultural activities and local communities were deprived of the natural resources they contained through expropriation and eviction.

One cannot deny the fact that these natural protected areas, which began to appear in the late 18th century and reached their peaked in the 20th century, constitute an invaluable source of ecosystemic benefits and have high potential in terms of the sustainable use of natural resources. In rural areas, the adoption of agricultural activities opens new spaces for other endeavors, such as tourism, which, given the new trend of leveraging natural resources, provides an economic alternative to local communities. Today, the basic objectives of conservation have been broadened to include public use, scientific interest and socioeconomic development.

According to Eagles, McCool and Haynes (2002), “a theme that runs right through the early history of protected areas is of people and land together, of people being as much a part of the concept as the land and natural and cultural resources” (p.8).

While the main objective of conservation areas is to protect and conserve natural resources, the creation and association of alternatives to facilitate a harmonious relationship between society and nature is still a pending debt in many spaces and territories. Several studies show that in Central America, there is a strong correlation between protected areas and communities with a low human development index (HDI) (Programa Estado de la Nación, 2008b). Many of the communities surrounding national parks with a tradition of agriculture or cattle farming are in conditions of poverty, lack employment opportunities and show limited evidence of identification with the neighboring conservation area.

According to a study of the Central Volcanic Conservation Area by Centeno, González and López (2012), the communities that were found to identify most with the nearest national park are those that have established cultural and environmental activities in association with the park, receiving economic and employment benefits from tourism. On the other hand, in communities where the relationship was rated regular to poor, tourism is seen as a way to strengthen the relationship between the community and the park.

Nel and Andreu (2008) write that tourism development policies aim to identify a strategy for positioning the country as a tourist destination and to serve as an instrument for making protected areas profitable and self-sustainable as well as for promoting local development. Local communities have benefited greatly from the rise in conservation areas in the past four decades and, in turn, have formed part of the strategy to contribute to the sustainability of the natural protected areas.

In that regard, Pauchard (2000) observes that the challenges protected areas will face in the future are centered on increasing the conservation of surrounding areas while incorporating local communities to a larger degree; mitigating the negative effects of ecotourism; and promoting low-scale tourism and research (p.51). Pauchard also writes that incorporating the community into the development of protected areas should be a priority and not simply a positive outcome of tourism, as this may be the only way to end the problems of illegal occupancy and exploitation of resources in protected areas that still linger in economically-challenged areas (p.59).

The document Políticas para las Áreas Silvestres Protegidas (ASP) del Sistema National de Áreas de Conservación (SINAC) de Costa Rica (Policies for the Protected Wildlife Areas of Costa Rica’s National System of Conservation Areas) (2011) addresses this concern, at least in terms of theoretical approach, and highlights key topics aimed at the relationship between protected areas and local communities:

a. Management of ASPs will incorporate local communities, indigenous populations, Afro-descendent communities and civil society organizations, recognizing traditional knowledge and ancestral practices;

b. Management of ASPs will focus on social equality, addressing and overcoming all forms of social, economic, cultural and/or political exclusion and inequality through concrete mechanisms of distribution of wealth and identification of resources and opportunities and through the promotion of intercultural and gender balance in decision-making;

c. Management of tourism in ASPs will be executed under a framework of sustainability, integrated with its areas of influence and in accordance with national conservation and tourism policies, plans and programs.

There is an obvious need to foster greater identification of the surrounding communities with national parks, conservation in general and with the rational use of resources, as well as to contribute to improving quality of life in these areas by promoting sustainable alternatives. On this subject, Maurín (2008) writes that geography’s synthetic methodology and unique position at the crossroads of the knowledge of nature and society could facilitate a better understanding and the treatment of some of the main problems that protected areas face today, almost always problems of coexistence, compatibility or synergy between environmental conservation and human activity (p. 168).

3. Costa Rica, Conservation and Tourism

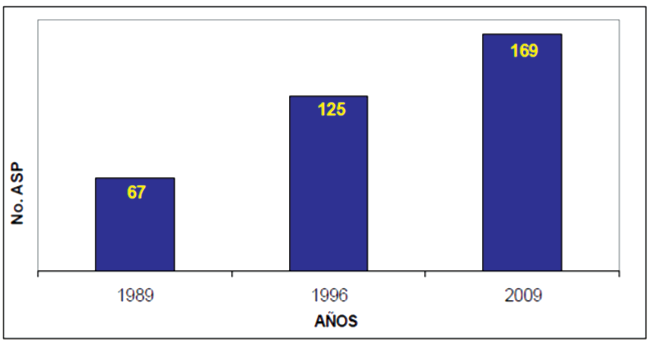

In Costa Rica, the number of natural protected areas has grown rapidly, the largest increase taking place between 1989 and 2009. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Number of Protected Wildlife Areas by decade, 1989-2009

Source: SINAC, 2010.

The first protected area to be declared in Costa Rica was the Cabo Blanco Absolute Nature Reserve created in 1963, followed by Santa Rosa National Park in 1971. According to SINAC (2011), today, protected wildlife areas represent 26.28% of national territory. The table below lists the number and total surface area of Costa Rica’s protected wildlife areas, classified according to ten management categories. Human presence is forbidden in the “national park” and “biological reserve” categories.

Table 1. Number and Total Surface Area of Protected Wildlife Areas in Costa Rica, 2013

|

Management Category |

Number of Protected Wildlife Areas |

Total Area Protected (acres) |

|

National Parks Biological Reserves National Wildlife Refuges Protected Areas Forest Reserves Wetlands Other Categories* |

68 8 75 31 9 13 5 |

2,730,117 66,323 686,847 390,192 534,682 169,383 25,946 |

|

Total |

169 |

4,600,490 |

Source: SINAC, 2013.

*Other Categories: National Monuments, Absolute Nature Reserves, Experimental Stations

For administrative purposes, the country’s System of Conservation Areas has been divided into eleven smaller areas, all under the management of the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC). These areas were redefined in the Biodiversity Act No. 7788, published in the nation’s Official Gazette No. 101 on May 27, 1998. Santa Rosa National Park falls within the Guanacaste Conservation Area (ACG, for its acronym in Spanish), located in northwestern Costa Rica bordering on the Pacific, and includes both land and marine areas. Moreover, it represents the biggest and only sample of dry forest between Mexico and Panama, with a surface area large enough to ensure perpetual conservation. In that regard, Panadero, Navarrete and Jover (2002), referring to the potential of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, place ACG as one of the primary areas of protection of a large portion of the region’s biodiversity.

3.1. Cattle Farming and the Disappearance of the Forest

Since colonial times, cattle farming has been the primary economic activity in Guanacaste; livestock trade with Nicaragua and the occupation of large expanses of land for pasture monopolized the landscape. An indication of this are the large extensions of the haciendas (cattle ranches), such as Santa Rosa measuring 15,679 acres, Murciélago measuring 6,672 acres, El Jobo with 11,841 acres, Paso Hondo with 21,251 acres, Orosi measuring 24,019 acres and Sapoa measuring 4,448 acres. This activity led to the rapid disappearance of dry forest beginning as early as the 17th century (Sequeira, 1985).

While cattle ranches required the installation of large open areas for pasture, annual fires and farming activity were detrimental to the recovery of the forest, benefiting the prevalence of the dry, fire-resistant flora native to the ignimbrite meseta, thus fostering the formation and expansion of the savanna (Vargas, 1982-1983).

The Guanacaste region was officially annexed to Costa Rican territory in 1858 when the Cañas-Jerez Treaty defined the northern border between Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Today, this border, known as La Cruz-Peñas Blancas, is an important transit area for millions of dollars of merchandise a year on its way through Central America. In addition, the area is a growing region for several export crops, including oranges.

Over the years, however, both agriculture and cattle farming activities have gradually been abandoned, evidenced in the smaller populations employed in these sectors in the last several censuses, whereas employment in the tertiary sector, or services sector, is on the rise (see Table 2). This trend can be observed in the recovery of forest areas as a result, mainly, of the declining dynamism of the cattle farming industry, although smaller cattle and agricultural farms still remain.

Table 2. Canton of La Cruz, Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica: Percent of population employed per sector of the economy

|

Year |

Sector of the Economy |

||

|

Primary |

Secondary |

Tertiary |

|

|

2011 |

37.2 |

9.5 |

53.3 |

|

2000 |

47.4 |

12.4 |

40.2 |

|

1984 |

71.4 |

5.97 |

22.97 |

Source: INEC, Population Census, 1984, 2000 and 2011.

3.2.Santa Rosa National Park, Territory and Resources

Santa Rosa National Park (PNSR, for its acronym in Spanish) was originally declared a national monument, then known as Casona de Santa Rosa (Santa Rosa Mansion), by law No. 3694 on July 1, 1966. On March 27, 1971, it was declared Santa Rosa National Park and was later expanded by executive decree in 1977, 1982, 1987, 1990 and 1991. Moreover, in 1980, it was expanded to include the Murciélago Sector, also by executive decree.

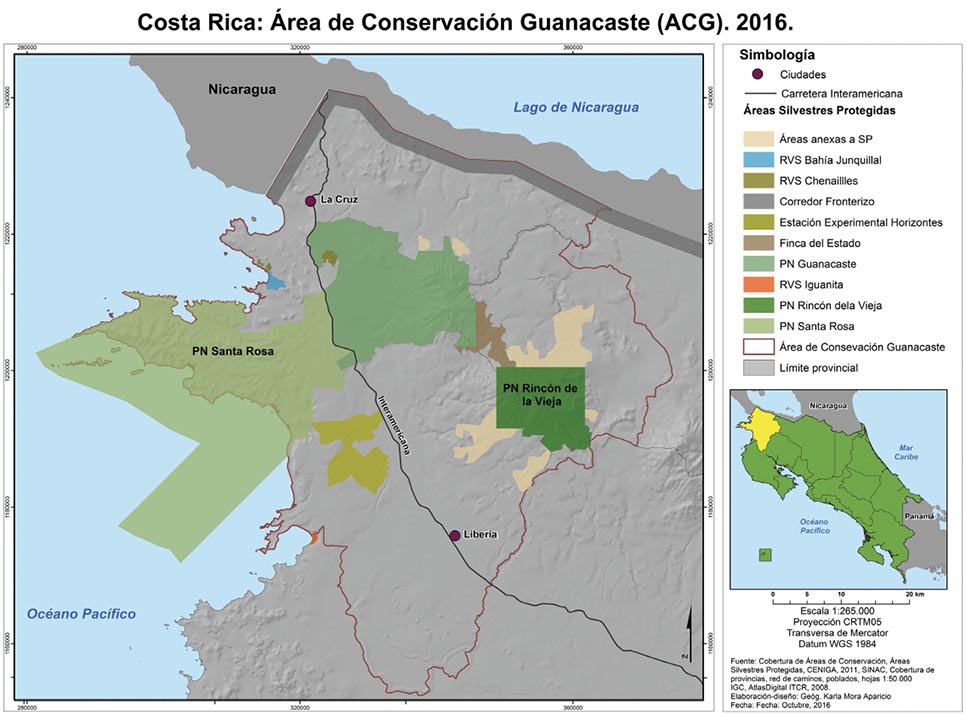

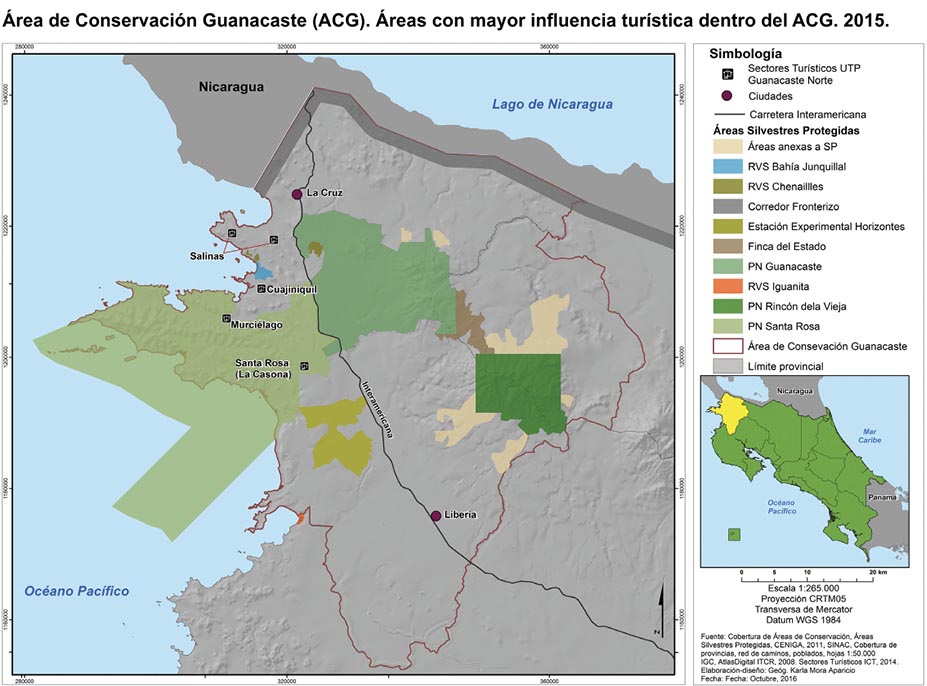

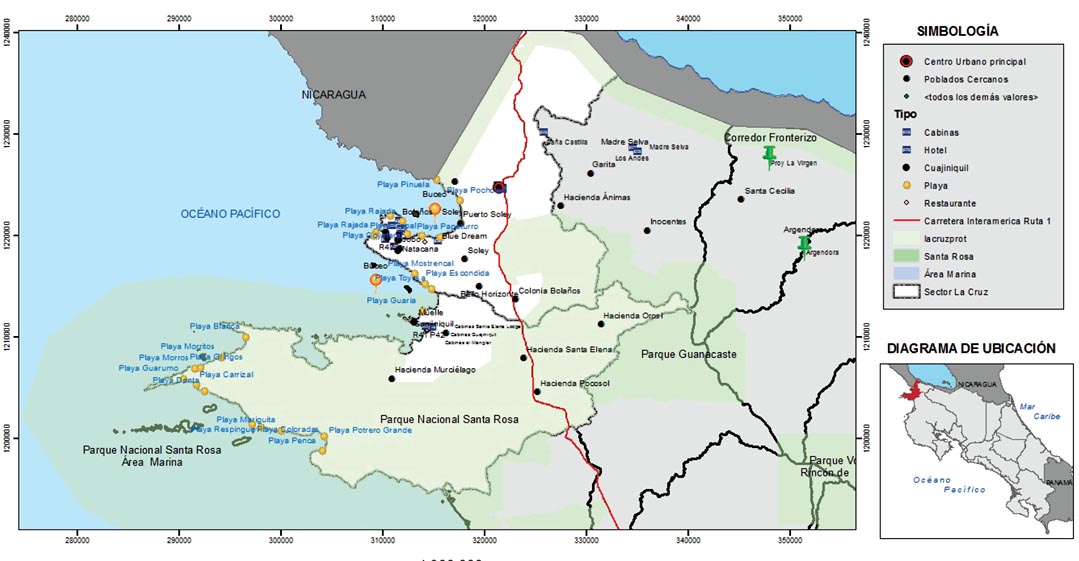

PNSR is part of the Guanacaste Conservation Area (ACG) and shares resources with other important areas, such as Rincón de la Vieja National Park, Junquillal Wildlife Reserve and Guanacaste Park, among others. Figure 2 below shows the distribution of the ACG, where the large marine area under protection is particularly noticeable, with the Inter-American Highway running right through the middle. The area borders on Nicaragua to the north with what is known as the Border Corridor Wildlife Refuge.

As a whole, the ACG was established in 1986 for the purpose of conserving the entire tropical dry forest ecosystem as well as those surrounding it, such as the cloud forest, rain forest and coastal area. Originally, the conservation area spanned only 25,700 acres, but in later years, focus was placed on buying up private lands. Today, the area encompasses 296,526 acres of land territory and 106,255 acres of marine territory. It is estimated that approximately 235,000 species (65% of all species in Costa Rica) exist in the area, representing 2.6% of the world’s biodiversity (SINAC, 2013). In 1999, the area was admitted as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. (See Figure 2).

The area protects the most emblematic dry forest in Central America, with tree species such as: the guanacaste (Enterolobium cyclocarpum, also known as the elephant ear tree), the pochote (Pachira quinata), the courbaril (Hymenaea courbaril), the gumbo limbo (Bursera simaruba) and mahogany (Swietenia humilis); mammal species including white-tailed deer, howler monkeys, white-headed capuchins and white-nosed coati; and numerous bird and amphibian species. The National University’s International Institute for Wildlife Conservation and Management (ICOMVIS, for its acronym in Spanish) is currently studying the importance of the ACG for the conservation of the jaguar (Panthera onca) and its prey as species indicative of forest recovery (Amit, Alfaro and Carrillo, 2007).

Figure 2. Guanacaste Conservation Area (ACG)

Santa Rosa National Park itself encompasses an area of 106,255 total acres of marine territory and 93,900 acres of land territory. The park has facilitated the restoration of old pasture areas into primary and secondary forest through processes of natural succession. The area is categorized as a tropical dry forest, characterized by a long dry season (six or seven months of the year), during which the vegetation will lose its leaves, and scarce water resources. Shortly after the creation of Santa Rosa National Park in 1971, a process of ecological succession began; annual wildfires that engulf the savannas of the tropical region are generally of anthropogenic origin (Vargas, 2011). Vargas goes on to mention that if the savanna were to be protected, it would evolve into a scrubland or even dry forest.

The Guanacaste Conservation Area is currently facing the real problem of territorial fragmentation. The area’s transportation network isolates key natural relicts and exposes the area’s fauna to death. In recent years, a project has been proposed to expand the national highway, but actions are being taken to ensure that it will not traverse the 13 kilometers of the ACG, as that would result in the destruction of flora and would put the animals in danger as they cross the road.

3.3. Key Geographical Characteristics of Santa Rosa National Park

Santa Rosa National Park is located in the canton of La Cruz, Guanacaste, which encompasses an area of 1,383 km² (534 mi2), 50% of which is under the protection of SINAC.

According to the geologic map of Costa Rica (1968), the area possesses the oldest rock in the country. PNSR consists of intrusive rock known as peridotite from the Santa Elena Peninsula (TT) as well as some fragments from the Nicoya Complex (Kvs), including graywacke, chert, shale, limestone, basalt columns and agglomerates and diabase, gabbro and diorite intrusions. Furthermore, constituents of the Barra Honda Formation (Tep-bh) can be found to the north of PNSR.

Geomorphologically, the area is characterized by forms of denudation originating in igneous rock, specifically the mountains and deep valleys of the Santa Elena Peninsula. Moreover, one can find forms of alluvial sedimentation, including colluvial-alluvial fans and colluvial-alluvial fans with possible marine influence. To the north of PNSR one can find geologic structures such as the monocline of Murciélago, the anticline of Descartes and the syncline de Cuajiniquil.

According to the life zones proposed by Holdridge in 1987, a large part of the territory in which PNSR and the surrounding areas are located hosts the largest representative sample of tropical dry forest (bs-t) in Central America, located on the basal layer, as well as a premontane wet transition to basal forest located on the premontane layer.

The area’s precipitation regime is characterized by long periods of drought, which usually run from November to May or June. In recent years, the territory has experienced prolonged dry spells, being one of the areas most affected by the El Niño phenomenon and climate change projections. The hydrological network includes intermittent rivers and, in general, the insufficiency of water in PNSR limits tourism development in the coastal areas. The communities in the area have limited access to potable water and, during the dry season, this becomes one of the main constraints to the population’s well-being.

3.4. Historical and Cultural Legacy of Santa Rosa National Park

Santa Rosa National Park offers a number of important natural and cultural resources for tourism, two of the most important being Hacienda Santa Rosa and the Murciélago Sector, both of which hold important historical relevance for the country.

a. Hacienda Santa Rosa. Once one of the most important trade posts between Liberia and Rivas, Nicaragua, the estate is a great symbol of Guanacasteca savanna culture. On March 20, 1856, it was the site of the historic battle against the oppressive intentions of William Walker and the filibusters. The estate evokes memories of the heroic feat of a small group of Costa Rican soldiers who were the first to face William Walker. Surrounding the estate are a number of resources and picturesque landscapes, including Naked Indian Trail, Tierras Emergidas Overlook, Monument to the Heroes, La Casona History Museum, Los Patos Trail, Naranjo Valley Overlook, Naranjo Beach (great for surfing) and Witches Rock. Nancite and Naranjo beaches, located within the boundaries of PNSR, are not only places of incredible scenic beauty, but are also important nesting beaches for olive ridley and leatherback sea turtles.

The original building that houses the La Casona History Museum was built in 1750. Today, the museum displays photographs, pictures, paintings and military weapons to commemorate the Battle of Santa Rosa. The stone corrals located near to the mansion were built in the year 1700 (approximately) and one can still see the tethering post and immersion baths today.

The original mansion, the park’s main tourist attraction, was burned down by arsonists in 2001 and was later reconstructed. It recently required additional repairs to ensure adequate conditions for tourism and to preserve history. Furthermore, PNSR is home to important resources for research, including labs, ecotourism programs, biology programs, research stations, conference rooms and other infrastructure and equipment. (See Figure 3).

Figure 3. Santa Rosa Mansion: Main tourist attraction at Santa Rosa National Park

|

Symbol of Guanacasteca culture The majestic Santa Rosa Mansion (current site of the history museum) Stone corrals Immersion baths |

SANTA ROSA ESTATE A combination of architectural, cultural and historical elements associated with the picturesque landscapes of the tropical dry forest. |

Source: Geographical Information Systems, ACG, 2004.

b. Murciélago Sector. The existence of Murciélago Farm (meaning “bat” in English) was recorded as early as the year 1663 and, since that time, passed through the hands of several different owners. In 1966, it became the property of Luis Somoza Debayle, former president of Nicaragua. During the Sandinista Revolution in 1979, the government of Costa Rica expropriated the farm from the Somoza family and, in 1980, part of the estate came under the administration of the Guanacaste Conservation Area. Today, the mansion at Hacienda Murciélago houses the National Police Academy, which occupies an area of 173 acres. A large part of the original estate has been set aside for protection, conservation and the police training center. Among the top tourist attractions of the Murciélago Sector are: El Nance Trail, Poza del General (a local swimming hole) and El Hachal, Santa Elena Bay and Blanca beaches, all of which, while possessing incredible scenic beauty, do not receive many visitors due to the difficulty to access the area. (See Figure 4).

Figure 4. Hacienda Murciélago Has Impressive Historical Value

|

Hacienda Murciélago Mansion |

Santa Rosa National Park Murciélago Sector |

|

|

|

In “Protected Areas: A geographical approach” Manuel Maurín (2008) proposes the hierarchical classification of resources into three categories: resources of primary interest, resources of significant interest and resources of lesser interest. Based on this methodology, we offer the following classification of the resources available at Santa Rosa National Park. (See Table 3).

Table 3. Guanacaste Conservation Area, Santa Rosa National Park: Hierarchical classification of resources, 2014

|

Resources of Primary Interest |

Resources of Significant Interest |

Resources of Lesser Interest |

|

Santa Rosa Sector |

||

|

Santa Rosa Mansion |

Monument to the Heroes Nancite Beach Naranjo Beach Turtle Nesting Flora and Fauna |

Naked Indian Nature Trail Tierras Emergidas Overlook Witches Rock Los Patos Trail Naranjo Beach Overlook Carbonal Trail Pozo Trail Naranjo Valley Overlook Carbonal Mountains Santa Elena Mountains |

|

Murciélago Sector |

||

|

Santa Elena Bay |

Santa Elena Beach El Hachal Beach Blanca Beach |

El Nance Trail Poza El General Swimming Hole |

Source: Compiled using the methodology proposed by Maurín (2008, p.170)

3.5. Marine and Coastal Resources Neighboring Santa Rosa National Park

The coastal zone that extends from Thomas Bay in La Cruz to the hills of Carbonal, Liberia, encompasses an area of 110 km (68 miles) and includes the country’s most important archipelago of fifteen islands, including Murciélago, Los Negritos, Bolaños and Los Cabos islands in Salinas Bay and Muñecos and Loros islands in Junquillal Bay, all important habitats for the nesting of seabirds. Moreover, Nancite Biological Station does research on the olive ridley turtle, while the San Jose Island Station researches coral in the area.

Located along the coastline are the communities of Cuajiniquil, El Jobo and Puerto Soley, all of which have come to heads with the park for practicing illegal fishing of artisanal fish and shrimp and scuba diving. According to the ACG (2014), the area is home to an abundance of coral reefs, fish species such as sailfish, marlin, sharks, mackerel, tuna, manta rays, golden cownose rays and spotted eagle rays as well as other ocean mammal species such as dolphins and whales, especially humpback. Similarly, sea turtles are known to nest in the area, specifically the olive ridley, Pacific green, leatherback and hawksbill varieties.

The area is susceptible to the upwelling phenomenon of the Gulf of Papagayo, which, according to the ACG (2014), occurs during the dry season when trade winds from the north push out massive amounts of surface waters from the Pacific Ocean, forcing deeper, colder waters to rise and bring with it nutrients from the ocean floor, thus increasing primary productivity. According to Méndez (2005), this is particularly true of the ACG marine areas, which are known by fishermen as sanctuaries. The area receives heavy pressure from the fishing industry as well as from tourism, which has been on the rise in recent years (p.55).

As a whole, the ACG has implemented the Strategy for the Regulation of Conservation and Management Actions throughout the 106,255 acres of the Guanacaste Conservation Area’s Protected Marine Sector, which aims to ensure that the sector’s marine and coastal biodiversity and all associated ecosystems are conserved and managed efficiently so as to ensure their continuation, and in which the environmental awareness of the local population and visitors contributes to the area’s conservation and development. Tourism for recreational purposes (such as scuba diving and observation) is permitted within the protected marine area, as is surfing and camping on San Jose Island, but these activities are governed by the corresponding regulations.

According to information available from the ACG (2012), funds from nine different countries, more than 50 international foundations and more than 10,000 private donors, totaling more than $50 million, have been invested in establishing the area. Moreover, more than 300 different properties were acquired to form the biological unit that today is in a process of restoration and conservation, representing 2% of the national territory of Costa Rican and hosting 2.6% of the world’s biodiversity.

4. Neighboring Communities of Santa Rosa National Park and Points of Interconnection

The area surrounding Santa Rosa National Park has a rich history associated with cattle ranches.

4.1. Community of Cuajiniquil: From day laborers to farmers and fishermen

The community of Cuajiniquil was founded on the practice of primary activities, specifically agriculture and fishing, and a large majority of the town’s inhabitants worked as farm laborers on Hacienda Murciélago. Due to the expropriation of approximately 38,940 acres of the estate, however, 4,942 acres were given to ITCO (the Institute of Land and Colonization, known today as the Rural Development Institute or INDER), another significant portion to Santa Rosa National Park and 173 acres to the National Police. Once the estate had been expropriated, a number of former farm laborers from the community of Cuajiniquil banded together to petition for access to the land. As a result, approximately 89 families (470 people) were awarded plots of land measuring 37-50 acres each. According to ITCO (1979), of the petitioners, 22 were of Nicaraguan origin with legal residency in Costa Rica.

The assessment made by ITCO in 1979 revealed that the farm’s terrain was very rough, with only small areas suitable for agriculture given the land’s topography. A large portion of the estate borders on the Pacific Ocean at Cuajiniquil Bay and Blanca beach, a condition that favored the conservation of a large part of the estate, specifically, the lands that were awarded to the ACG.

From the very beginning, water supply has been an issue for the Cuajiniquil community, and as of 1979 no water supply had been planned. According to ITCO (1979), at the time, the majority of the area’s inhabitants received their water from wells, ravines and springs. In later years, this has been a main issue of contention between PNSR and the community, as several neighboring parcels do not have water resources and the occupants have traditionally taken it from the park for irrigation and domestic use. While formal documents exist granting the concession of water, water supply has not been guaranteed in recent years.

4.2. From Hacienda El Jobo to the Community of Colonia Bolaños

The community of Colonia Bolaños, situated along the Northern Pan-American Highway, was founded after an invasion of Hacienda El Jobo, which was designated for extensive cattle farming (the majority of these lands are not suitable for agriculture). The original farm on which Colonia Bolañas was established spanned an area of 3,500 acres, 2,345 of which were divided up between 33 families by ITCO (62 acres per family) and the remaining 1,155 acres were designated for conservation. Guanacaste Park later bought up many the lands awarded to the families and, today, these form part of the ACG.

As the closest community to the park, in recent years, a community outreach strategy has focused on the fight against forest fires. Education provided by the park and the incorporation of volunteers from the community have vastly improved the relationship. Based on our interviews with members of the community, we were able to observe an optimistic attitude regarding the community’s relationship with the park, considering that, for years, the latter was viewed by many as a competitor after having incorporated agricultural and cattle farms into the national park, thus limiting access to land resources.

4.3. Puerto Soley and El Jobo: Coastal Communities

Puerto Soley and El Jobo are located along the area’s coastline. Both are established on former cattle ranches that were expropriated and divided up by ITCO/INDER. These areas, known for their pristine beaches, have received heavy pressure from tourism, resulting in the arrival of foreign investors and, consequently, the sale of the land by the owners. The construction of hotel infrastructure and growing tourist services threaten these coastal areas and the survival of the communities.

4.4. La Cruz: Border town and secondary distribution center

The city of La Cruz, Guanacaste, is the primary services center in the border canton of the same name, which, as previously stated, encompasses an area of 1,383 km² (534 mi²), 50% of which is under the protection of SINAC. La Cruz has a population of 19,181 inhabitants (INEC, 2011) and an illiteracy rate of 6.23%, occupying the 69th position of Costa Rica’s 81 cantons on the Social Progress Index. The city of La Cruz is located 20 km (12.5 mi) from the country’s northern border, and, as such, is popular for the practice of visaje3 tourism. On the other hand, the provision of services aimed at tourism is scarce in the main center, with only a minimum number of hotels and restaurants.

4.5. Ciudad Blanca, Liberia: Intermediary distribution center

Liberia, the main population center and capital of Guanacaste Province, offers a significant number of services aimed at tourism4. Daniel Oduber Quirós International Airport5 is situated in close proximity to the city and Liberia itself is located just 30 km (18.5 miles) from Santa Rosa National Park. As a result, it is the perfect point from which to travel to the nearby beaches and important conservation areas in this part of the country, including PNSR and Rincón de la Vieja National Park, in less than an hour and along well-maintained roads. This explains, in part, the lack of tourism development in the communities directly surrounding PNSR.

5. Tourism, Santa Rosa National Park and Local Communities

Tourism to the Guanacaste Conservation Area is on the rise given its wealth of natural resources, the most important of which is Santa Rosa National Park. Many of the areas within the boundaries of the ACG have free public access, while others are restricted, designated exclusively for research and conservation. Table 4 below lists the sectors of interest to tourism, education and research.

Table 4. Sectors of Interest to Tourism in Santa Rosa National Park and the Guanacaste Conservation Area, 2014

|

Sectors of Interest to Tourism, Education and Research |

|

|

Santa Rosa Sector* |

La Casona History Museum, the main tourist attraction; Naranjo beach |

|

Murciélago Sector* |

Wealth of dry forest, beaches and mangroves; geological significance; mountains of the Santa Elena Peninsula; oldest land in Costa Rica |

|

Las Pailas Sector |

Rincón de la Vieja is the most visited site in the ACG; active volcanic crater, picturesque landscapes, flora and fauna |

|

Junquillal Sector |

Junquillal Bay Wildlife Refuge located along the coastline offers significant biological wealth |

|

Santa María Sector |

Part of Rincón de la Vieja National Park; spectacular views, biological wealth and volcanic manifestations |

|

Horizontes Experimental Forest Station |

Observation of tropical dry forest, birds and forest species; mountain biking |

|

Marine Sector |

Located in the Gulf of Papagayo, intended to protect the marine ecosystem; recreational tourism, including scuba diving and surfing |

Source: Compiled using information available from the Guanacaste Conservation Area, 2014.

* Note: These two sectors are located inside Santa Rosa National Park, while the remaining areas are part of the Guanacaste Conservation Area as a whole.

Figure 5. Guanacaste Conservation Area: Major tourist attractions, 2015

Santa Rosa National Park houses the Ecotourism Program, which promotes and monitors tourism activity in the conservation area. Tourism to the ACG is varied; the areas that receive the largest number of visitors are Rincón de la Vieja National Park, Santa Rosa National Park and Junquillal Wildlife Refuge, while visitation to Guanacaste Park and Horizontes Experimental Forest Station is very low.

Similarly, the ACG’s Education Program, created in 1986, is currently implemented at 53 education centers, reaching approximately 2,500 students, and includes three curriculums: biological education, marine bio-awareness and environmental education. The program has produced a series of educational products, including a virtual dry forest, the Rothshildia bulletin and species pages, all accessible online. In the summary of activities in environmental education for II cycle students (ACG, 2011), the ACG acknowledges Dr. Daniel Janzen6 for having a clear vision of the future and for teaching them to read the great books that take the form of the forest.

Guanacaste became popular in the 1980s as a local tourist destination, offering pristine beaches, protected areas and sports fishing among its main attractions. While development is strong in some sectors, it is weak in others, as is the case of the ACG as a whole, whose tourism development has been classified as emerging with tourist attractions in the form of natural resources. According to the tourism inventory methodology applied by the North Guanacaste Tourism Unit (TT Argos, 2008), 55% of the area’s attractions are classified as Category I or insufficient to motivate strong tourism; 37% are classified as Category II or having a certain level of attraction for tourism; and 17% as Category III in that they are very attractive for tourism, offering some exceptional characteristics, as is the case of Santa Rosa National Park.

Similarly, Blanco (2007) classified the area’s natural and cultural resources according to their importance, as shown in Table 5 below.

Table 5. Canton of La Cruz, Guanacaste: Natural and cultural attractions, 2014

|

Attraction |

Category |

Activities |

|

Santa Rosa National Park |

III |

Hiking, flora and fauna, horseback riding tours, cycling and relaxation |

|

La Casona History Museum |

III |

History |

|

Junquillal Wildlife Refuge |

II |

Hiking and swimming |

|

Orosi Volcano |

II |

Hiking, flora and fauna |

|

Cuajiniquil, Puerto Soley, El Jobo, La Rajada and Copal Beaches |

I |

Aquatic sports, fishing and relaxation |

|

Sapoa, Hacienda Ánimas, Sábalo and Mena Rivers |

I |

Fishing and relaxation |

|

Bolaños Island |

I |

Bird watching |

|

Mesoamerican Biological Corridor |

I |

Rivers, flora and fauna |

Source: Compiled based on Blanco, M. (2007, p.46) and field work in 2014.

Moreover, there are a number of cultural activities, including patron saint festivals with typical foods, horse parades, bull running and music.

In the National Sustainable Tourism Plan for Costa Rica, 2010-2016, the Costa Rican Tourism Board (ICT) indicates that the area has a high level of natural attraction. This study divides the North Guanacaste Tourism Unit into three sectors:

a. Salinas. Corresponding to the canton of La Cruz, where towns are small and spread out, as is the case of Puerto Soley and El Jobo, and offer few services, but have an emerging tourism sector.

b. Cuajiniquil. The only town in the sector is Cuajiniquil, all other settlements are single-family homes situated on farms; tourism development is non-existent, but could be tied to La Cruz and Libera as major tourist centers.

c. Santa Rosa National Park. Comprising the coastal area and lands within the boundaries of Santa Rosa National Park.

Unlike other areas, urban development is not centered along the coastline, but rather inland, along the international highway, and, historically, are agricultural and cattle farming centers, such as Liberia and La Cruz. The occupation of coastal areas is attributed to the advancement of the agricultural frontier, favoring the establishment of smaller towns and communities along secondary roads, which have remained relatively isolated.

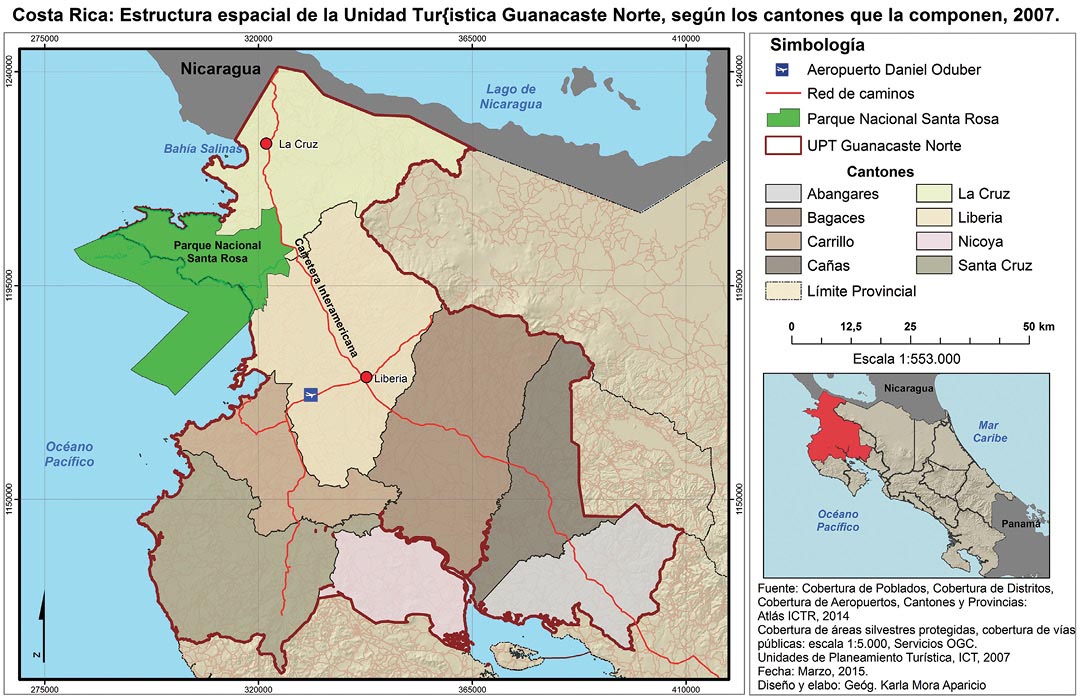

According to the ICT (2007), the unit’s many attractions do not constitute a unified axis by virtue of the existence of Santa Rosa National Park; the attractions located to the north directly influence the city of La Cruz, while the attractions to the south form an axis related to the city of Liberia. Santa Rosa National Park, which is located within the unit, has become a key point not only for the sector, but also for the rest of the unit (p. 92). From Liberia, one can directly access Santa Rosa National Park, Cuajiniquil and Junquillal and, from there, secondary routes lead to Salinas Bay. La Cruz operates as a secondary access point to the Salinas Bay area. (See Figure 6).

Based on information from the ICT (2012), Liberia operates as a distribution center along National Route 1 (the Inter-American Highway) for tourism from the other Planning Units (Central Valley, Northern Plains or Central Pacific) as well as for international tourism coming from Nicaragua.

What is clear, however, is that despite its early creation in 1971, Santa Rosa National Park itself did not generate tourism development. For this to occur, public policy is needed to generate and promote private investment, something that is only occurring now given the tourism development plan for 2010-2016.

Figure 6. Spatial Structure of the North Guanacaste Tourism Unit, based on cantons, 2007

5.1. Visitation and the Dynamism of Tourism

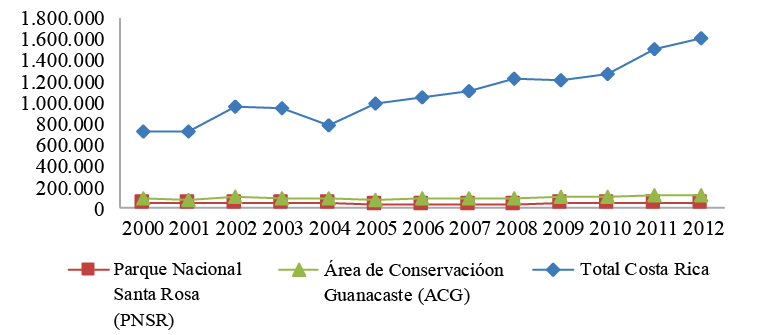

Figure 7 below is indicative of how visitation to Costa Rica’s natural protected areas has grown constantly since the year 2000, experiencing only slight declines in 2004 and 2009.

Figure 7. Total Number of Tourists to Protected Areas, 2000-2012

Source: Based on information from the ACG Ecotourism Program, 2012.

Santa Rosa National Park tends to receive a larger number of national visitors than foreign tourists (see Table 6 below), given that its main resource, the Santa Rosa Mansion, lives in the memories of Costa Ricans as the site of a famous historic battle that is taught in schools from the very first levels of primary education. On the other hand, we can see that Rincón de la Vieja National Park receives many more foreign tourists. Other areas within the ACG receive very few visitors as is the case of Guanacaste Park and the Horizontes Experimental Forest Station. In an interview with Guadalupe Rodríguez, a public servant at PNSR, Rodríguez informed us that visitors establish a relationship between the two parks, PNSR and Rincón de la Vieja National Park (PNRV), given that when visitors arrive, they are given information about PNSR and the other conservation areas they can visit, since the ACG is seen as a system. Guanacaste Park is visited more by organized biology groups who visit Maritza Biological Station to observe petroglyphs, cocoa, pitilla and the forest.

Table 6. Guanacaste Conservation Area: Tourism to national parks according to nationality, 2013

|

ACG Park |

National |

(%) |

Foreign |

(%) |

Total |

|

Santa Rosa National Park |

25,076 |

71.58 |

9,959 |

28.42 |

35,035 |

|

Rincón de la Vieja National Park |

12,771 |

22.38 |

44,312 |

77.62 |

57,083 |

Source: Guanacaste Conservation Area, 2013.

International tourists come primarily from the United States, France, Germany and Canada, as shown in Figure 8 below.

In terms of national tourism, a large percentage of visitors come from the provinces of Guanacaste (41%), San Jose (28%) and Alajuela (13%). Visitation is highest during school holidays, Holy Week, Christmas, New Years and during the dry season in general. During the rainy months, most visitors come on primary and high school field trips. Visitation is lowest on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays; however, given that Rincón de la Vieja National Park is closed on Mondays, tourists will normally head to PNSR.

On days with low visitation, the park tends to receive an average to 20 people, while over a weekend, it may be visited by 50 people per day and visitation is even higher over a long weekend. According to information provided by Guadalupe Rodríguez, in 2014, tourism to Santa Rosa peaked at 4,126 visitors, double that of the previous year, due, in part, to the Historic Trail Campaign and, in part, to the drought in Guanacaste that motivated people to leave home.

National tourists, who tend to visit the Santa Rosa Mansion (generally on a guided tour), the Monument to the Heroes and Naked Indian Nature Trail, tend to stay in the park for an average of two hours. On the other hand, international tourists, in addition to visiting these sites, also take the trails that lead down to the beaches and overlooks, especially to Naranjo beach, which, despite lacking a decent access road, is accessible via 4x4 during the dry season. Nancite beach is closed to the public, having been designated for research purposes only. The roads that access the beaches in PNSR are in poor overall condition and extremely difficult to transit, impossible even in a 4x4 during the raining season.

Figure 8. Guanacaste Conservation Area: Origin of international tourists, 2012

Source: Based on information from the ACG Ecotourism Program, 2012

Surfing is popular at Naranjo beach and so visitation depends on the behavior of the tide. Moreover, camping is permitted in the area, with a maximum capacity for 50 people. The lack of potable water is a problem, however, and each camper is required to bring their own. Despite this, visitors will usually stay for 2 to 3 days. While the area offers an abundance of nature trails, it is not apt for families with small children, and so it is likely that camping will soon be banned. When visitors enter the park and express a desire to visit the beaches, they are informed about the different tourist sites nearby, especially Junquillal beach and the Murciélago Sector, which offers an abundance of beautiful beaches, visited mostly by national tourists. Some of the most popular are El Hachal (5 km), Santa Elena Bay (8 km) and Blanca (17 km) beaches. While the beach roads are a bit difficult to transit, most are in adequate condition. (See Figure 9 below).

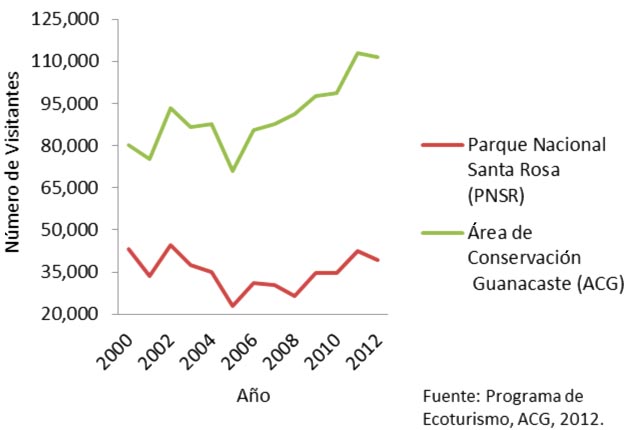

The capacity of Santa Rosa National Park does not represent a problem: the area is sufficiently ample and pressure from tourism is not much at this time. Currently, two important projects are underway at PNSR: 1) the construction of a Universal Trail for people with physical limitations (funds were raised with the support of a private company); and 2) collaboration with the community via the Non-Essential Services Project, still in the initial phase, which plans for the surrounding community to offer some of the services in the lower categories, such as camping, stores, beach transportation, sodas (small cafés), etc.

Figure 9. Visitation to Santa Rosa National Park Compared to

ACG as a Whole, 2012

Source: Based on information from the ACG Ecological Program, 2012.

5.2. Structure and Distribution of Tourist Services

In the two communities adjacent to Santa Rosa National Park, Cuajiniquil and Colonia Bolaños, tourist services are scarce. During a trip to the area, we were able to confirm that Cuajiniquil has a total of two restaurants and three hotels: Hotel Cabinas Cuajiniquil (2011), Hotel Santa Elena Lodge (2006) and Cabinas Manglar (1994) with three, ten and four rooms, respectively. With the exception of Cabinas Manglar, the hotels were all established recently. On the other hand, Colonia Bolaños offers no accommodations whatsoever and only two restaurants, both established in 2014.

Tourist services in the surrounding communities, including La Cruz, El Jobo, Puerto Soley, Sonzapote and La Garita, are also limited, but are much more varied. As is to be expected, a large number of the hotels are located in La Cruz and in the coastal communities of El Jobo and Puerto Soley. More specifically, there 17 hotels in the area offering a total of 711 rooms. As seen in Table 7 below, 447 new rooms were recently inaugurated in the coastal community of El Jobo, an area that, according to the ICT (2012), has been designed for concentrated tourism, evidencing the rise of tourist services in the coastal area.

In the area’s main population center, tourist services are limited, although basic services are available, such as restaurants. Based on information from the ICT (2012), there are 12 hotels in the area, only two of which have a Tourism Declaration and none a Certificate of Sustainable Tourism. During our field work, we documented the existence of five additional hotels that were inaugurated more recently, for a total of 17 distributed around the canton. (See Table 7).

Table 7. La Cruz, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Accommodations in and around La Cruz, 2014

|

Name |

No. of Rooms |

Name |

No. of Rooms |

|

Hotel Dreams Las Mareas* |

447 |

Hotel Amalia’s Inn |

9 |

|

Hotel Bolaños Bay Resort |

72 |

Cabinas Peñas Blancas Bar and Restaurant |

9 |

|

Cabinas Santa Rita |

38 |

Hotel Bar and Restaurant Faro Del Norte |

8 |

|

Ecoplaya Beach Resort |

36 |

Cabinas Marifel |

7 |

|

Hotel Bello Vista |

20 |

Finca Cañas Castilla |

6 |

|

Hotel Colinas Del Norte |

15 |

Tierra Madre Eco Lodge Hotel |

5 |

|

La Mirada Hotel |

12 |

Cabinas Manglar |

4 |

|

Hotel Blue Dream |

10 |

Hotel Cabinas Cuajiniquil |

3 |

|

Hotel Santa Elena Lodge |

10 |

||

|

Total |

711 |

Source: Based on information from the ICT (2014) and field work.

*Dreams Las Mareas was inaugurated in November of 2014.

According to the Costa Rican Tourism Board (2007), in the area of study, tourist facilities are associated mostly with the major attractions along the coastline. A line has yet to be drawn to other complementary services that could help establish a tourist circuit and encourage the diversification of tourism activities (p. 108). Moreover, the ICT indicates that natural attractions are currently operating as complements to the primary form of sun-and-sand tourism. These coastline attractions are located at the axis of Salinas Bay and Descartes Point and are considered to be Category III attractions with positive conditions for tourism development (p. 92).

During our field work, we observed that agritourism and other alternative tourism projects, as well as a number of tourist services such as hotels and villas, are located outside of the major tourist areas. At this time, the Chamber of Tourism is being reactivated in the city of La Cruz, which will look to integrate these projects into a tourist circuit, so as to benefit communities that up to now have remained cut off from tourism.

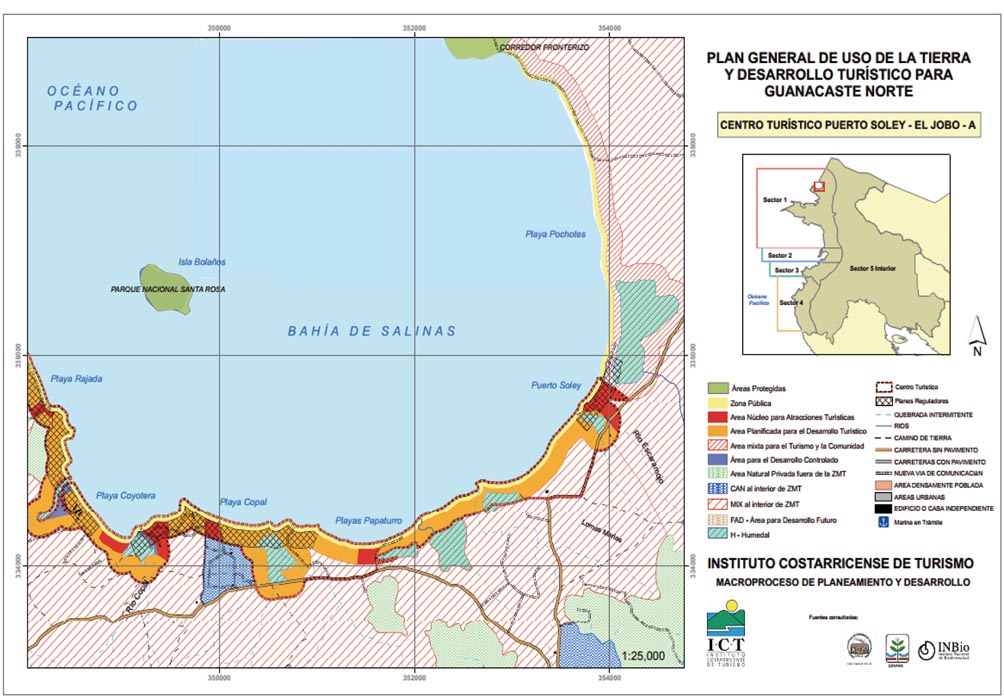

Figure 10 below shows the distribution of tourist services in terms of accommodations (hotels and villas), restaurants and sodas, agritourism projects and the major tourist attractions at the beaches in Santa Rosa National Park. As we can observe, these tourist resources and services are concentrated along the coastline with only a few newer projects located in the mountain and border areas. Santa Rosa National Park, for its part, forms a type of barrier between these communities and the city of Liberia.

Figure 10. Tourist Resources and Services in the Areas Surrounding Santa Rosa National Park, 2014

We can conclude from the distribution of tourist resources in the map above that tourism is related first and foremost to the sun and sand, given the concentration of services around Santa Rosa National Park in the canton of La Cruz, Guanacaste. Table 8 below incorporates a list of the key tourist resources and services (also seen above in Figure 10) that promote tourism in the canton, thus demonstrating that PNSR is the major tourist attraction and that, from there, visitors move on to visit other sites.

Table 8. Canton of La Cruz and Surrounding Areas: Tourist services in the areas surrounding Santa Rosa National Park, 2014

|

Villas |

Hotels |

Restaurants and Sodas |

Tourist Attractions |

|

Bolaños |

Amalia’s Inn |

El Pirata |

El Recreo Overlook |

|

Caña Castilla |

Bella Vista |

El Rancho |

Cuajiniquil Pier |

|

Marifel |

Blue Dreams |

Marakabú |

Papaturro Beach |

|

Santa Rita |

Bolaños |

Pescadería Goal |

Rajada Beach |

|

Mirador Pta. Descartes |

Dreams Las Mareas |

Pizzería |

Soley Beach |

|

Cuajiniquil |

Ecoplaya |

Plaza Copal |

|

|

El Manglar |

Punta Descartes |

Neighboring Towns |

|

|

Agritourism Projects |

El Recreo |

Soda Male |

Cuajiniquil |

|

Argendora Vanilla |

Foro del Norte |

Soda Thelma |

La Garita |

|

La Virgen, basic grains |

Hospedaje del Sol |

La Gloria |

|

|

La Mirada |

La Virgen |

||

|

Madre Selva |

Los Andes |

||

|

Santa Elena Lodge |

|

Natacana |

Source: Based on field work, 2013-2014.

According to the ICT (2007), development policy for the area should be based on the application of the concept of concentrated development7 in tourist centers and areas of limited tourism development. The sector’s dynamism suggests the establishment of a single tourism development center at Puerto Soley/El Jobo, as this area is characterized by the development of medium quality services aimed at certain population segments, as well as many sun-and-sand activities, beach sports, relaxation and aquatic activities. This development is concentrated, firstly, on the beaches of Papaturro, Copal, Coyotera, Rajada, El Jobo and West Rajada and, secondly, on Pochote and Puerto Soley (p. 120-123).

Figure 11 above shows the tourism zoning scheme for the coastal area based on the General Land Use and Tourism Development Plan for Northern Guanacaste, which outlines the major tourist areas, a mixed tourism and community area and areas of planned and controlled tourism development. This indicates that tourism is expected to grow in upcoming years under the sun-and-sand model and, as such, coastal resources will play a decisive role in tourism development.

6. Sustainable Tourism in the Areas Surrounding Santa Rosa National Park, Guanacaste

Several tourism experiences in the canton of La Cruz suggest that alternative tourism projects are on the rise, which could eventually be integrated into the current sun-and-sand model. These new experiences include small-scale tourism, production chains, use of local materials, organic agricultural production, regeneration of pastures and leveraging landscapes and forest resources, among others.

6.1. Cañas Castilla Bungalows

Inaugurated in 1994, Cañas Castilla is a project located in Sonzapote, La Cruz, 10 km (6 mi) from Costa Rica’s northern border. The property, which belongs to a Swiss couple, encompasses a total area of 146 acres, where the couple has built furnished bungalows with a capacity of two to four people. Visitors to the project stay an average of three days and come primarily from Switzerland, Canada, Poland and other European countries. They offer accommodations, meals, hiking trails, horseback riding, observation of flora and fauna and beach tours. Moreover, demand is complemented by a very peculiar type of tourism known as visaje tourism, given the proximity of the project to the Nicaraguan border.

Figure 11. General Land Use and Tourism Development Plan for Northern Guanacaste: Puerto Soley/El Jobo Tourist Center, 2007

The property has several hiking trails and guided tours are offered either on foot or horseback. Moreover, the project implements environmental measures and uses only energy efficient systems. The owners have made an effort to integrate into the community and to contribute to local development projects. This project, born two decades ago, is based on a highly-developed sense of environmental awareness, and, while the owners have faced economic difficulties due to low visitation, maintains a constant level of demand throughout the year.

6.2. Science Tour, Cuajiniquil

Mainor Lara, a resident of the town of Cuajiniquil, Guanacaste, worked as a park ranger in the marine sector of Santa Rosa National Park from 1995-2000, when he retired to set up his own business, leveraging his years of experience and environmental awareness. Mr. Lara believes that the close proximity of the park has stifled development in the area, in addition to the lack of water, which limits the expansion of tourism. His new job consists of guiding groups of science students in different sustainable activities, such as snorkeling, scientific diving and observation tours. He works with universities who send him groups of students with marine-related scientific interests.

When interviewed, Mr. Lara was with a group of ten students from the University of California who, at the time, were taking a course on Tropical Biology and were working on marine-related projects, including the observation of coral, fish, iguanas and geckos in protected and burned areas. Students are transferred by boat to the recommended areas, where Mr. Lara accompanies them during their tour and enrichens their experience with his extensive knowledge. In addition, Mr. Lara works with biologists from every area of knowledge, and he himself is familiar with the ocean, coastline and appropriate sites for scientific experiences and has taken courses both at home and abroad. During the high season, Mr. Lara will receive six to eight groups a month of 20 students each. For scientific tourism, the high season runs from May to November, given that, starting in December, the waters are colder and the wind is stronger. Regardless, Mr. Lara receives an average of 600 people a year.

These groups of scientists stay in the area for an average of three months and are provided accommodations in the homes of members of the community, who have experience in housing visitors of this type. Mr. Lara has developed a network of contacts within the community for the provision of services, such as those who provide seafood, hotel accommodations, tortillas, boat rentals, etc.; thus at least six more people benefit indirectly from Mr. Lara’s business. He can be contacted via his website, email or phone.

Mr. Lara maintains a close relationship with Santa Rosa National Park, which sends him visitors who express an interest in this type of science tourism; he believes the park knows they do the job well. Mr. Lara stated that he believes that tourism in the area can be consolidated as long as people are responsible when it comes to conservation. He believes fishing is less productive; those who work in tourism can earn more.

6.3. Basic Grains Project, La Virgen, Santa Cecilia

Founded in 2005, the Basic Grains Project is run by an association of 14 women and one man. They produce and market basic grains using organic technologies, including beans, rice and corn, as well as corn derivatives such as pinol (toasted corn flour), pinolillo (a beverage made from toasted corn flour and cocoa beans), pozol (corn and pork soup) and pujagua (purple corn). Four years ago, they incorporated rural tourism into their project, offering horseback riding, hiking and transportation to the overlooks of Lake Nicaragua. They offer demonstrations of the rice and corn processing machines as well as demonstrate how to milk a cow. They also provide meals. In the near future, they would like to build bungalows for visitors to stay and already have ample land for expansion.

6.4. Vanilla Project, Argendora, Santa Cecilia

The Vanilla Project, now in the business of growing vanilla for eight years, is led by a group of women and encompasses seven parcels of land measuring 17 to 20 acres each. Given that vanilla belongs to the orchid family, it constitutes the nexus between the forest and agroforesty systems: in the short term, the grower cultivates and sells the vanilla, while, in the long term, obtains the wood.

The production of vanilla eases the pressure on the forest through the sale of the orchid, which is economically viable. Advised by the National University’s Institute for Research and Forestry Services (INISEFOR), this group of women have taken their project to the next level: in addition to selling the vanilla, they now receive tourists who visit the vanilla plantations on guided tours.

6.5. Tierra Madre Eco Lodge Hotel

This project is the initiative of a Belgian couple who decided to move to Costa Rica and put down roots. It is located in an area with a beautiful natural landscape and an impressive view of Lake Nicaragua, which shows the process of recovery of what were once cattle farms in the foothills. In 2010, the couple bought a farm measuring approximately 170 acres, now under a process of regeneration.

The hotel, located in Los Andes, La Garita in La Cruz, Guanacaste, has five bungalows with a maximum occupancy of 12 people and is intended for small-scale tourism. Everything the hotel consumes is produced on the property itself: a small organic vegetable garden produces sufficient food to feed the guests; the construction materials for the bungalows were produced using the soil found on the property, as well as from leveraging the landscape and forest resources; lighting and electricity comes from solar panels; and the bathrooms feature dry flush toilets and showers that do not generate extreme amounts of foam that could be harmful to the environment. Although it will be a challenge to attract tourists to a place as difficult to access as Tierra Madre Eco Lodge Hotel, those who do arrive are very specially motivated. Tourist services include walking and horseback riding tours around the property and along the nature trails and day trips to Cárdenas, Nicaragua, and Lake Nicaragua.

6.6. Other Related Activities

Other activities, such as the Turtle Festival, suggest efforts are being made to strengthen the relationship between the community and tourism and conservation. This annual festival, which began in 2009, encourages a type of tourism that takes into account the local conditions of the area’s population. At the festival, locals sell handicrafts made from local materials, and there are presentations and information on the importance of the sea turtles and the need to preserve the species. It is a space that has gained recognition among locals and foreigners alike, who come to enjoy concerts, sports and local artisanal demonstrations. In 2014, the festival was held on the weekend of November 22-23.

6.7. Future Alternatives: Geological formation and geotourism in Santa Elena

Santa Rosa National Park has been proposed as a geopark, which assumes a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development focused on geological sites of particular importance, rarity or aesthetics (“geosites”). A geopark achieves its goals through three major pillars: geoconservation, education and geotourism.

In “Geoparks in Latin America,” Mantesso-Neto, et. al. (2010) write that the first geopark in Costa Rica will be founded on the site of Santa Rosa National Park, encompassing an area of 370 km2 (143 mi2) of land territory and 780 km2 (301 mi2) of marine territory in the extreme northwest of the country. The area possesses elements of geological, biological and historical heritage.

7. Conclusions

The unique characteristics of the natural landscape of Guanacaste Conservation Area consist of an extensive marine platform, adjacent coastal areas and mountains surrounding the sea, considered to be the oldest lands in Costa Rica. The prevalence of tropical dry forest with its corresponding ecosystems, a savanna landscape and the existence of natural protected areas that are home to a variety of natural and cultural resources transform the area into a space of incredible beauty with high tourism potential.

The ACG, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1999, is a site of research for both national and international universities, given that it is believed to host more than 65% of the country’s biodiversity. The area offers a variety of tourist attractions, from the Santa Rosa Mansion to Murciélago estate and all of the natural and cultural resources these contain, as well as exquisite beaches along the coast of the canton of La Cruz, including Santa Elena Point, Puerto Soley, Junquillal and El Jobo.

Santa Rosa and Rincón de la Vieja National Parks receive the largest number of visitors to the Guanacaste Conservation Area. The former receives many more national visitors, while foreign tourists are more prone to visit the latter. Today, the area of study is being impacted by tourism, which, consequently, is changing land use in the area. Spontaneous, unplanned tourism could generate undesirable effects on the environment and local populations, which, due their natural and cultural resources, have become objects of consumption of tourism. The areas surrounding Santa Rosa National Park are experiencing emerging, yet rapidly growing tourism dynamics, especially in coastal areas where accommodation services have increased, especially in Puerto Soley and Rajada.

Like with other areas, the sun-and-sand tourism model has shaped tourism; however, several initiatives are under way around the canton to leverage other natural and cultural resources. These sustainable tourism initiatives have managed to identify elements that could strengthen rural development even more in the canton, such as small-scale tourism, use of local materials, organic agricultural production, regeneration of degraded areas, recovery of forests and related ecosystems (flora and fauna), leveraging landscapes and forest resources, employing family and local labor, generation of supplementary income, production chains, cultural recovery (customs and traditions) and fostering environmental awareness in new generations. These initiatives require incentivization and support in order to offer a service in keeping with visitors’ needs and for them to be identified with the other tourist services offered around the canton.

Programs sponsored by the Guanacaste Conservation Area in areas surrounding the protected areas, such as the Research Program, Environmental Education Program and Biological Education Program, are proof of a strengthening relationship between the protected areas and the community. These programs where introduced in the 1990s and are intended for the last three years of primary school and the first three years of high school as a way to bring awareness to the local population. Common topics such as forest fires have brought the community and conservation areas closer together as a way to avoid the impact they could have on the area’s resources.

Given that almost 50% of the total area of the canton of La Cruz is protected under one of the different conservation categories and, seeing that the surrounding communities could develop tourist activities given the area’s potential, especially that of its primary natural resource, Santa Rosa National Park, and the numerous beaches that surround it, efforts are needed to ensure that the community benefits from these resources. Organization is fundamental in coordinating these efforts and, consequently, in offering consistent tourist services. These initiatives have all been envisioned by the Chamber of Tourism of La Cruz, which was recently established with the support of institutions and organizations from around the canton, including the Guanacaste Conservation Area.

Acknowledgements

Consuelo Alfaro Chavarría and Karla Mora Aparicio, thank you for your collaboration with the cartography.

References

Amit, R., Alfaro, L. and Carrillo, E. (2007, October). Área De Conservación Guanacaste y Conservación del Jaguar [Guanacaste Conservation Area and conservation of the jaguar]. Revista Ambientico, 169, 16-18.

Área de Conservación Guanacaste (ACG). (2011). Compendio de Actividades de Educación Ambiental para Escolares de II Ciclo [Summary of activities in environmental education for II cycle students]. Guanacaste, Costa Rica.

Área de Conservación Guanacaste (ACG). (2012, February 16). ¿Qué es el ACG? [What is the ACG?]. Retrieved from https://www.acguanacaste.ac.cr/acg/que-es-el-acg

Área de Conservación de Guanacaste (ACG). (2014a). Programa de Ecoturismo [Ecotourism Program]. Retrieved from http://www.acguanacaste.ac.cr/biodesarrollo/programa-de-ecoturismo

Área de Conservación de Guanacaste (ACG). (2014b). Sector Marino [Marine Sector]. Retrieved from http://www.acguanacaste.ac.cr/biodesarrollo/sector-marino

Belletti, Claudio. (2014, August 21). Cabinas Manglar. Personal Interview.

Blanco, M. (2006). Análisis del potencial de turismo rural en los cantones de Upala, Los Chiles, Guatuso y La Cruz [Analysis of potential rural tourism in the cantons of Upala, Los Chiles, Guatuso and La Cruz]. IICA-PRODAR. San José, Costa Rica.

Blanco, M. (2007). Dinámicas territoriales en la Zona Norte de Costa Rica [Territorial dynamics in Costa Rica’s northern zone] (2nd ed.). IICA. San Jose, C.R.

Centeno, J., González, H. and López, N. (2012, February). Percepción de las comunidades sobre el ambiente y la relación con los parques nacionales cercanos [Community perception of the environment and relationship with nearby national parks]. In Comunidades y Áreas Silvestres Protegidas: identidad, convivencia y conservación ambiental/Nacional University (Costa Rica). School of Social Sciences. Institute for Social Studies in Population. 2nd ed. Heredia, Costa Rica: UNA-IDESPO.

Diegues, A. C. (2000). El mito de la naturaleza intocada [The myth of untouched nature]. Quito, Ecuador: Abya Ayala.

Eagles, P., McCool, S. and Haynes, Ch. (2002). Sustainable tourism in protected areas: Guidelines for planning and management. United Nations Environment Programme, World Tourism Organization and UICN – The World Conservation Union. Thanet Press Limited: United Kingdom.

Fonseca, Jorge Manuel Alan. (2014, August 21). Hotel Santa Elena Lodge. Personal Interview.

Furst, E., Moreno, M., García, D., and Zamora, E. (2004). Desarrollo y conservación en interacción: ¿Cómo y cuánto se beneficia la comunidad de las áreas protegidas en Costa Rica? [Development and conservation in interaction: How and by how much do Costa Rica’s protected areas benefit the community?] Heredia, Costa Rica: CIMPE, UNA.

Gonzaga, Alexandra. (2014, August 22). Public Servant at the Municipality of La Cruz. Personal Interview.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC). (2011). Indicadores cantonales: Censos Nacionales de Población y Vivienda 2000 y 2011 [Cantonal Indicators: National population and housing censuses for 2000 and 2011]. Programa Estado de la Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible. San Jose, Costa Rica.

Instituto Costarricense de Turismo (ICT). (2007). Unidad de planeamiento Guanacaste Norte. Plan de Uso del Suelo y Desarrollo Turístico Macroproceso de Planeamiento y Desarrollo 2007 [North Guanacaste Planning Unit: Land-use planning and tourism development; Planning and development macro processes, 2007]. San Jose, Costa Rica.

Instituto Costarricense de Turismo (ICT). (2010). Plan Nacional de Turismo Sostenible de Costa Rica, 2010-2016 [National plan for sustainable tourism in Costa Rica, 2010-2016]. San Jose, Costa Rica.

Instituto Costarricense de Turismo (ICT). (2012). Anuario Estadístico de Turismo 2012 [Yearbook of Tourism Statistics, 2012]. San Jose, Costa Rica.

Instituto Costarricense de Turismo (ICT). (2013). Anuario Estadístico de Turismo 2013 [Yearbook of Tourism Statistics, 2013]. San Jose, Costa Rica.

Instituto Costarricense de Turismo (ICT). (2014). Área de Conservación Guanacaste [Guanacaste Conservation Area]. Retrieved from http://www.visitcostarica.com/ict/paginas/es_parques_gua.asp

Instituto de Tierras y Colonización. (1979). Estudio socio-económico del grupo campesinos de Cuajiniquil Guanacaste [Socio-economic study of farmers in Cuajiniquil, Guanacaste]. Departamento de selección y capacitación de beneficiarios. San Jose, Costa Rica.

Lara, Mainor. (2014, November 20). Science Tours Operator, Cuajiniquil. Personal Interview.

Mairena Corea, Naftali. (2014, August 22). President of the Chamber of Commerce and Tourism of La Cruz, Guanacaste. Personal Interview.

Mantesso-Neto, V., Mansur, K., López, R., Schilling, M. and Ramos, V. A. (2010). “Geoparques en Latinoamérica” [Geoparks in Latin America]. VI Congreso Uruguayo de Geología, Parque de Ute Minas, Lavalleja.

Maurín, M. (2008). Las áreas protegidas: un enfoque geográfico [Protected areas: A geographical approach]. Ería, 76, 165-195.

Méndez, G. (2005). Estrategia marina del Área de Conservación Guanacaste [Guanacaste Conservation Area’s marine strategy]. In the biannual magazine of the School of Environmental Sciences of the National University of Costa Rica, 30.

Nel, M. and Andreu, L. (2008). Organización y características del turismo rural comunitario en Costa Rica [Organization and characteristics of rural tourism in Costa Rica]. Anales de Geografía, 28 (2), 167-188.

Panadero, M., Navarrete, G. and Jover, F. (2002). Turismo en espacios naturales: oportunidades en el corredor biológico mesoamericano [Tourism in natural spaces: Opportunities in the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor]. Cuadernos de Turismo, 10, 69-83.

Pauchard, A. (2000). La experiencia de Costa Rica en áreas protegidas [Costa Rica’s experience with protected areas]. Revista ambiente y Desarrollo, XVI (3), 51-60.

Programa Estado de la Nación. (2008a). XIV Informe Estado de la Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible [XIV State of the Nation report on sustainable human development]. Programa Estado de la Nación. San Jose, Costa Rica.

Programa Estado de la Nación. (2008b). III Reporte Estado de la Región en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible: Un informe desde Centroamérica y para Centroamérica [III State of the Region report on sustainable human development]. Programa Estado de la Nación. San Jose, Costa Rica

Rodríguez, Guadalupe. (2014, August 21). Public Servant at Santa Rosa National Park. Personal Interview.

Rodríguez, G. and Martínez, J. (2014). Informe de visitación 2013 Área de Conservación Guanacaste, Programa de Ecoturismo [2013 Visitation Report: Guanacaste Conservation Area, Ecotourism Program]. Guanacaste, Costa Rica.