Revista Geográfica

ISSN: 1011-484X

Número 58 Enero-junio 2017

Doi: dx.doi.org/10.15359/rgac.58-1.8

Páginas de la 195 a la 222 del documento impreso

Recibido: 15/6/2016 • Aceptado: 19/9/2016

|

Revista Geográfica ISSN: 1011-484X Número 58 Enero-junio 2017 Doi: dx.doi.org/10.15359/rgac.58-1.8 Páginas de la 195 a la 222 del documento impreso Recibido: 15/6/2016 • Aceptado: 19/9/2016 |

Evaluation of the recent intraplate seismic activity on Cochinos Bay, Cuba

Evaluación de la actividad sísmica de interior de placa reciente en la Bahía de Cochinos, Cuba

Mario Octavio Cotilla Rodríguez1

Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Ciudad Universitaria, s/n. 28040 Madrid

ABSTRACT

The geodynamic cells model to the Western Seismotectonic Unit of Cuba explains the occurrence of an intraplate earthquake (21.01.2015 / mb= 4.1 / h= 16 km / 22.216 N 81.422 W) in the Zapata Swamp – Cochinos Bay. The main seismic event is associated to the knot K8, Cochinos Bay, where two active faults (Cochinos and Surcubana) exist.

Keywords: Active fault, Cochinos Bay, Cuba, earthquake, intraplate seismicity

RESUMEN

El modelo de celdas geodinámicas para la Unidad Sismotectónica Occidental de Cuba explica la ocurrencia de un terremoto de interior de placa (21.01.2015 / mb= 4.1 / h= 16 km / 22.216 N 81.422 W) en la Ciénaga de Zapata – Bahía de Cochinos. El evento sísmico principal está asociado al nudo K8, Bahía de Cochinos, donde dos fallas (Cochinos y Surcubana) existen.

Palabras clave: Bahía de Cochinos, Cuba, falla activa, terremoto, sismicidad de interior de placa

Introduction

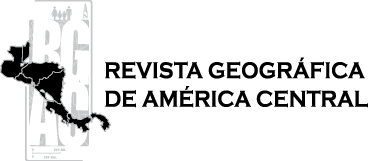

On 21.01.2015 (04:07:13 hours) an earthquake (mb= 4.1 / h= 16 km / 22.216 N 81.422 W, USGS data) shaked mainly the southern of the Matanzas province, Cuba (Figure 1). The epicenter is located in the surrounding of the Zapata Swamp [ZS] and Cochinos Bay [CHB]. It was perceptible (~103 km2) in some localities of 3 neighboring administrative provinces: 1] Cienfuegos: (1.1) Aguada de Pasajeros (100 km), (1.2) Cienfuegos City (75 km)); 2] Las Villas: (2.1) Corralillo (110 km), (2.2) Santa Clara City (130 km)); 3] Matanzas: (3.1) Calimete (65 km), (3.2) Central Australia (50 km), (3.3) Jagüey Grande [JG] (55 km), (3.4) Pedro Betancourt (70 km), (3.5) Torriente (60 km), (3.6) Unión de Reyes (90 km)).

Figure 1A. Epicenter of Zapata Swamp and Localities

Figure 1B. Cuban Seismic Intensity Map (original scale 1:1,000,000)

1A) A) Administrative provinces (CH-P= Ciudad de La Habana, C-P= Cienfuegos, LH-P= La Habana, LV-P= Las Villas, M-P= Matanzas, PR-P= Pinar del Río); B) Associated images (number inside a square: 5= Section of the North coast line between Corralillo and Cárdenas. The black arrow indicates the direction to Matanzas Bay (MB); 7= Segment of the coast Larga Beach, Cochinos Bay; 8= Predominant type of landscape in Zapata Swamp. The arrow indicates the direction to Jagüey Grande (JG)). (See Tables 1, 3 and 5); C) Black circle= epicenter of 21.01.2015; D) Geographic areas (BP= Bahamas Platform, GM= Gulf of México, SDB= Santo Domingo Basin, YB= Yucatan Basin); E) Localities (1= La Habana Bay (earthquake 1693), 2= Matanzas Bay (founded 1693), 3= Hicacos Penynsula, 4= Cárdenas, 5= Corralillo (founded 1879), 6= Cienfuegos Bay (founded 1745), 7= Cochinos Bay, 8= Zapata Swamp, 9= Jagüey Grande (founded 1850), 10= Güines (earthquake 1777), 11= San José de las Lajas, 12= Remedios, 13= Trinidad, 14= Sancti Spíritus, 15= Santa Clara (founded 1689), 16= Sagua la Grande, 17= Agramonte (founded 1859).

1B) A) Black discontinue square= the study region; B) Intensity value= 5 (MSK Maisí); C) Localities= CC (Cabo Cruz), CSA (Cabo de San Antonio), PM (Punta de Maisí); D) Two first earthquakes (1528-Baracoa, 1551-Cabo Cruz).

ZS is the largest swamp (~4.4x103 km2) in the Caribbean. It has only 10 small villages with low population (~9,000 inhabitants). The area had very extremly economic difficulties to the people since the colonial time, and it was isolated by several years. Until 1961 there were not electricity and stable roads. CHB is an historic place with a limited touristic profile (Girón Beach and Larga Beach).

Table 1. Main Earthquakes of the Western and Center Seismotectonic Units

|

Date |

Intensity (MSK) |

Magnitude / h (km) |

Locality, Province |

|

23.01.1880 |

8 |

(6.2) / 20 |

San Cristóbal, Pinar del Río |

|

28.02.1914 |

7 |

(6.2) / 20 |

Gibara, Holguín |

|

15.08.1939 |

7 |

5.6 / 15 |

Remedios-Caibarién, Las Villas |

|

11.06.1981 |

5 |

3.7 / - |

Alonso de Rojas-La Coloma, P. del Río |

|

16.12.1982 |

6 |

5.0 / 20 |

Torriente-Jagüey Grande, Matanzas |

|

09.03.1995 |

5 |

2.5 / 10 |

San José de las Lajas, La Habana |

|

09.01.2014 |

6 |

5.1 / 10 |

Corralillo, Las Villas |

|

21.01.2015 |

5 |

4.1 / 16 |

Ciénaga de Zapata-Bahía de Cochinos, Matanzas |

Note: The numbers in parenthesis indicate macroseismic determinations (see Figures 1 and 2) (2016).

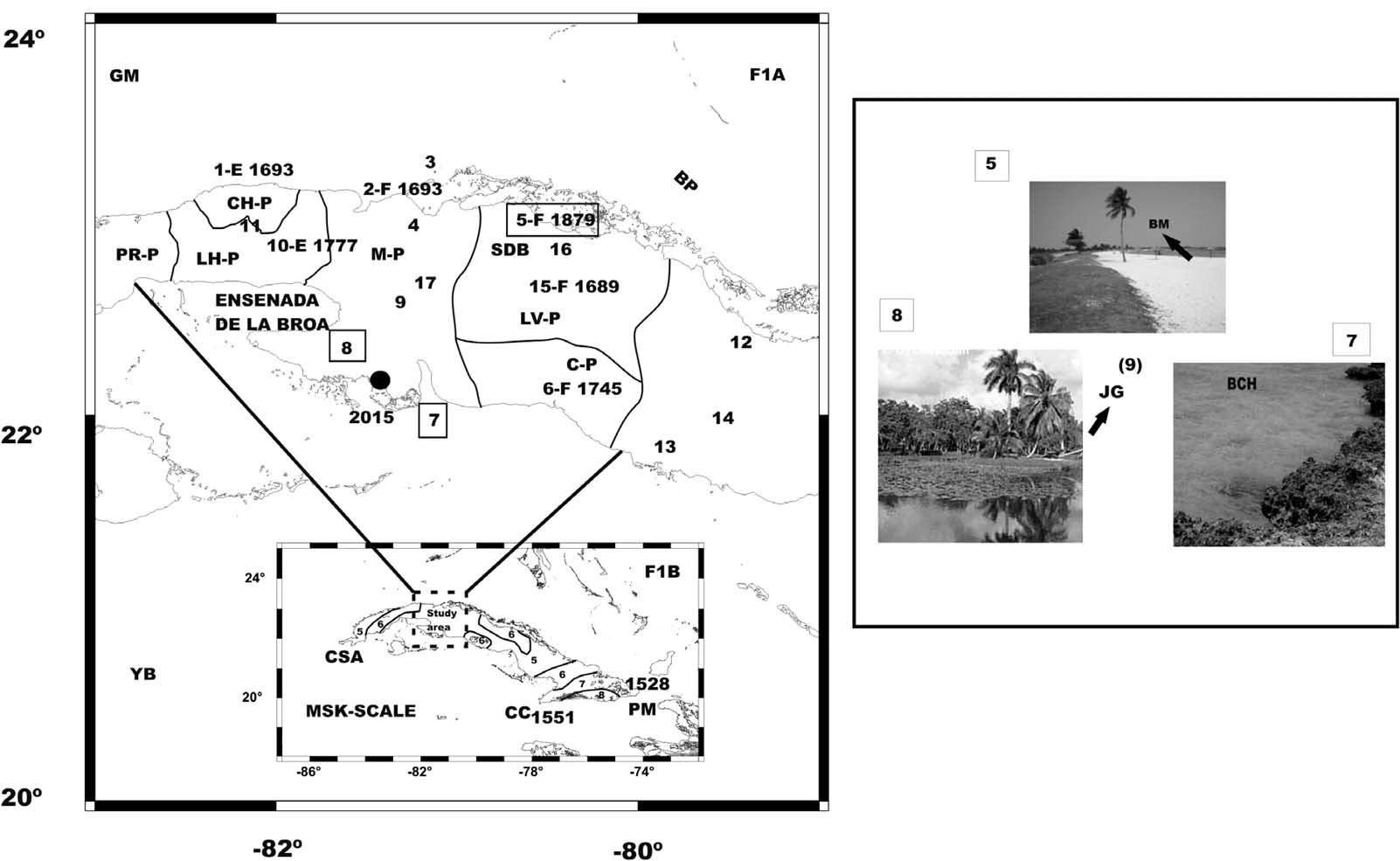

The earthquake above mentioned was registered in an intraplate zone, concretely in the Western Seismotectonic Unit (Wsu) (Figure 2). The first earthquakes reported there occurred in 1693 (Ciudad de La Habana) and 1777 (Güines) (Figure 1), but it had several perceptible earthquakes (Table 1). The most relevant happened (16.12.1982) in the vecinity of Torriente and JG, localities (Table 2) (Chuy et al., 1983). It represented the beginning for an alternative research to explain the seismicity in the Wsu (Álvarez et al., 1985; 1990).

The recent earthquake of ZS-CHB confirm principally: 1) the great differences in the reports by the international seismic networks and the Cuban seismic stations (Table 3). The first group get epicentral parameter values very near between them, and the second one (Cuban network) situated the epicenter more far to the E; 2) the seismic activity [SA] in the surrounding of CHB-JG (Cotilla, 1999A; Cotilla, 2014B); 3) the low energetic level of this area (Cotilla and Álvarez, 2001) (Figure 2); 4) the validity of the geodynamic cells model to explain the earthquakes occurrence (Cotilla et al., 1996A) (Figure 3A).

Our aim is to show the main information and fundamental elements, which can explain the earthquakes occurrence in the Wsu and in particular on the ZS-CHB area.

Figure 2. Seismotectonic Map of Cuba (Original Scale 1:1,000,000)

A) Black circle= epicenter (year= 1880) (see Table 11); B) Heavy line= Active fault (CNF). (See Table 9); C) Heavy short black arrow= Stress (E1, E2); D) Seismotectonic Units (Wsu= Western, Csu= Center, Esu= Eastern, Ssu= Southeastern); E) Type of seismicity (IPS= Intraplate, ITPS= Interplate); F) Grey circles= Knots (KNMG1, K1) (see Table 14); G) Localities (NB= Nipe Bay, G= Guane, GI= Gibara, P= Pilón, R= Remedios, SC= Santiago de Cuba).

Table 2. Data of the 16.12.1982 Torriente-Jagüey Grande Earthquake

|

Parameters |

Values |

|

Affected area (102 km2) |

34 |

|

Coordinates |

22º 37’ N 81º 14’ W |

|

Depth (km) |

20 |

|

Imax (MSK) |

6 |

|

Largest distance of perceptibility (km) |

~140 |

|

Ms |

5.0 |

|

Time of occurrence (UT) |

20:20 |

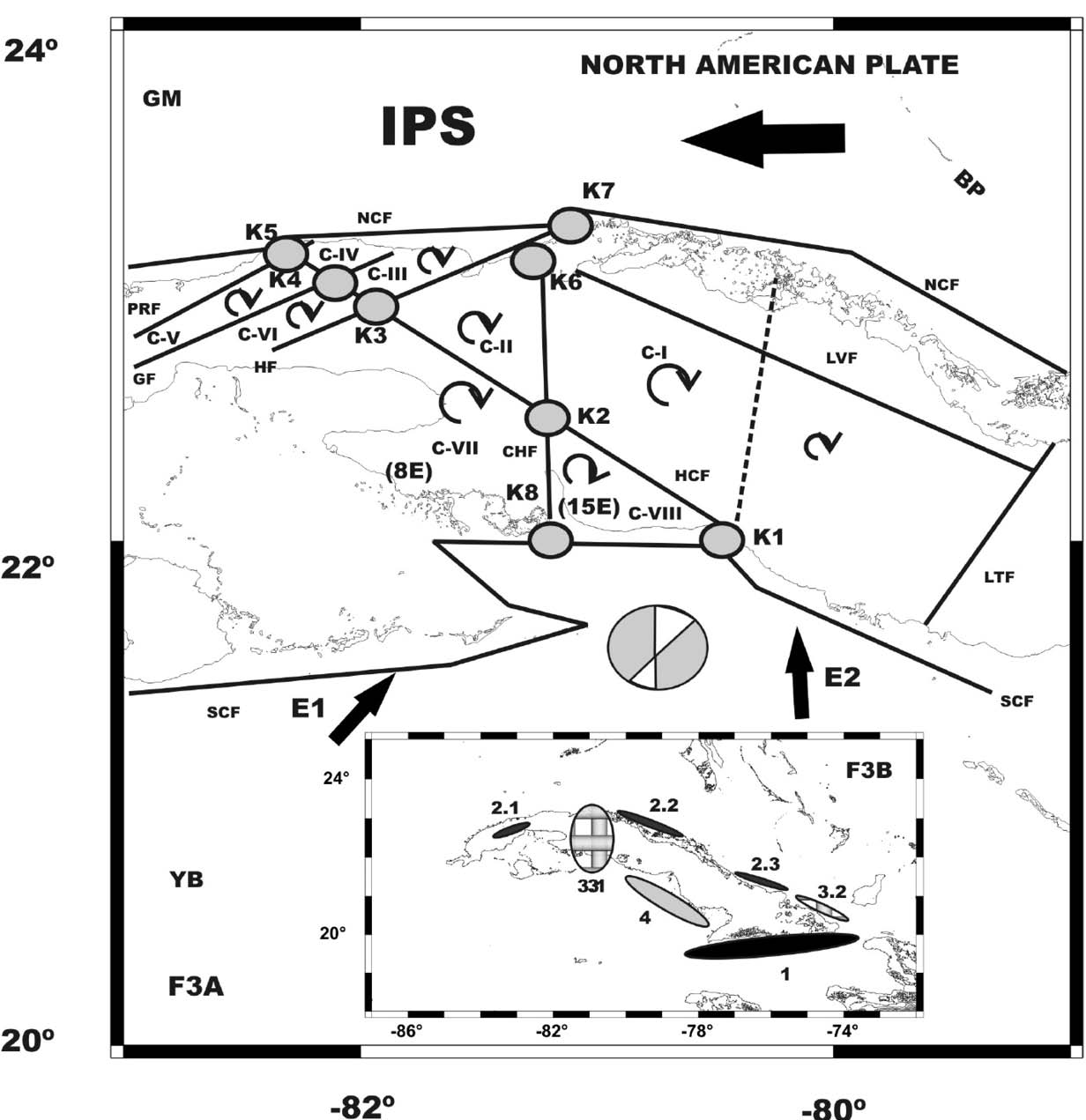

Figure 3A. Geodynamic Cells’ Model of the West and Center Regions

Figure 3B. Scheme of the Main Seismoactive Segments

3A) Appear: A) Black line= Active faults (HF) (see Table 9); B) Curve black arrow= Sense of blocks rotation; C) Heavy short black arrow= Stress (E1); D) Heavy large black arrow= Sense of plate movement; E) Geographic areas (BP= Bahamas Platform, GM= Gulf of México, YB= Yucatan Basin); F) Geodymanic cells (CI= East Matanzas, CII= Center Matanzas, CIII= Habana-Matanzas, CIV= La Habana, CV= West Habana, CVI= South Habana, CVII= Zapata-Cochinos (8 earthquakes), CVIII= Cienfuegos (15 earthquakes)); G) Grey circle= Knot (K5) (see Table 14); H) IPS= Intraplate seismicity; I) Theoretical focal mechanism solution (beach ball).

3B) Appear: Ellipses (1= Southeastern, 2= (2.1= Guane; 2.2= Remedios; 2.3= Gibara), 3= (3.1= Cochinos-Corralillo; 3.2= Nipe-Maisí), 4= Surcubana).

The Geodynamic Model

The basic fundaments by the seismotectonic model using geodynamic cells are in: 1) the maps and schemes of: 1.1) Lineaments and knots (Cotilla et al., 1991B); 1.2) Neotectonics (Cotilla et al., 1991C; 1996B); 1.3) Neotectogenic (Cotilla et al., 1996B); 1.4) Morphostructural (González et al., 2003); 1.5) Seismotectonic (Cotilla, 1993; 2014A; B; Cotilla and Álvarez, 1991; 1999; Cotilla and Franzke, 1999; Cotilla et al., 1991A; 1996B); 1.6) Seismic potentials (Cotilla et al., 1997B); 2) the compilation and evaluations of: 2.1) the earthquake catalogs (historic and instrumental); 2.2) the isoseismals data; 3) the analysis and improvements of the seismogenic zones in the schemes and models (Álvarez et al., 1985; 1990; Cotilla, 1999A; B; 2007; 2014A; Cotilla and Álvarez, 1991; 1998; Cotilla and Córdoba, 2011A; 2015; Cotilla and Udías, 1999A; B; Cotilla et al., 1988; 1996A; 1997A).

Table 3. Seismic Data of the Zapata Swamp-Cochinos Bay Earthquake

|

Agency |

Date / Time |

Coordinates |

h(km) |

Magnitude |

|

Cuban |

20.01.2015 / 11:07 |

22.34 N 81.22 W |

20 |

M(Richter)= 4.0 |

|

EMSC |

21.01.2015 / 04:07:13.9 |

22.25 N 81.39 W |

10 |

mb= 4.2 |

|

GEOFON |

21.01.2015 / 04:07:14 |

22.37 N 81.41 W |

10 |

mb= 4.6 |

|

USGS |

21.01.2015 / 04:07:10 |

22.216 N 81.422 W |

16 |

mb=4.0/Mw= 4.1 |

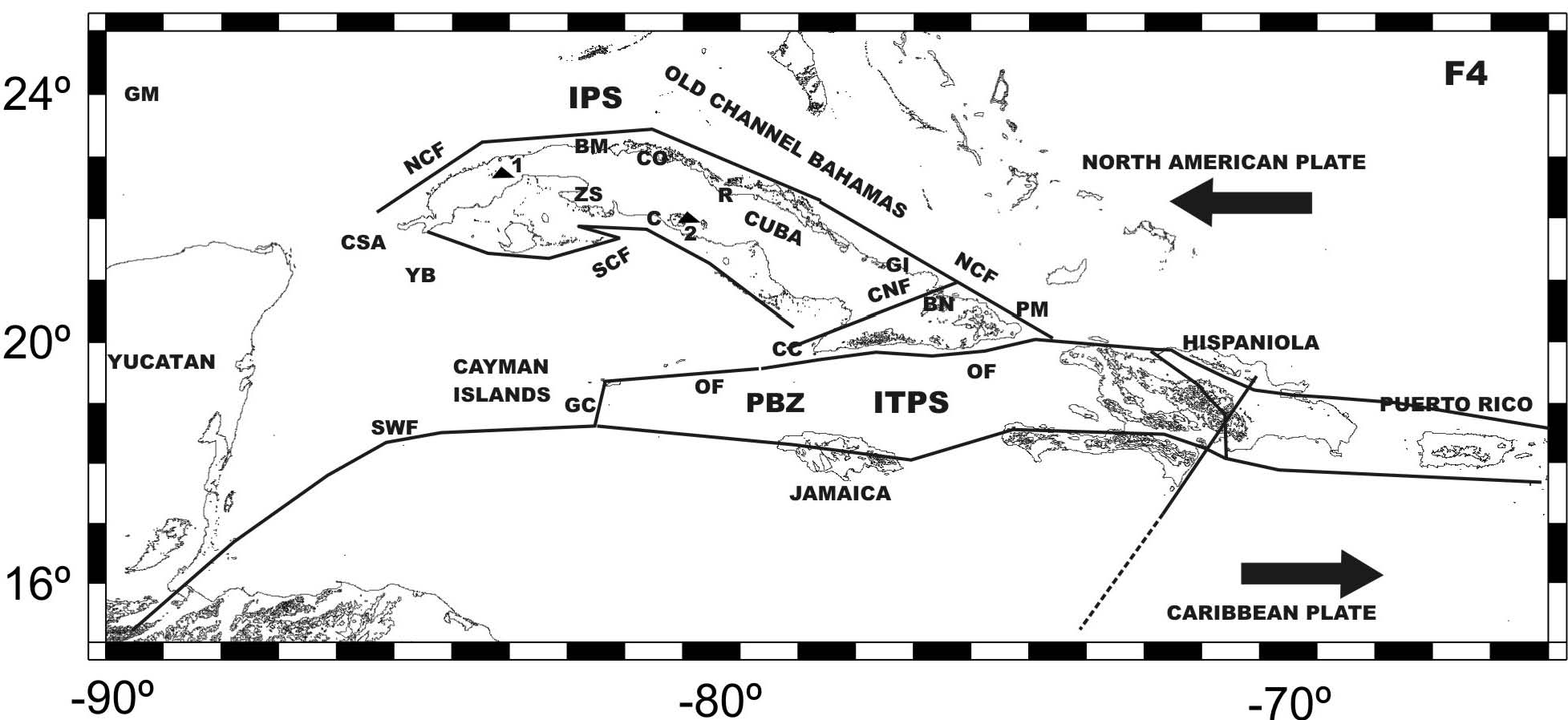

Figure 4. Tectonic Scheme of the Northern Caribbean

Appear: A) Black line= Active fault (CNF= Cauto-Nipe, NCF= Nortecubana, OF= Oriente, SCF= Surcubana, SWF= Swan-Walton); B) Black triangle= Seismic station (1= Soroa, Pinar del Río; 2= Manicaragua, Cienfuegos); C) Geographic areas (GC= , GM= Gulf of Mexico, YB= Yucatan Basin, PBZ= Plate Boundary Zone); D) Heavy black arrows= Sense of plate movements; E) Localities (MB= Matanzas Bay, NB= Nipe Bay, C= Cienfuegos, CC= Cabo Cruz, CSA= Cabo de San Antonio, ZS= Zapata Swamp, GI= Gibara, R= Remedios); F) Type of seismicity (IPS= Intraplate, ITPS= Interplate).

There were some papers that inspired to search scientific explanations about the Cuban seismicity as (Makarov and Schukin, 1976; ) Sibson, 1985; Spiridonov and Grigorova, 1980). The results of (Assinovskaya and Soloviev, 1994; Backmanov and Rasskazov, 2000; Guelfand et al., 1976; Gvshiani et al., 1987; Mackey et al., 1977; Sherman and San`kov, 2010; Stein and Yeats, 1989; Zhidkov, 1985; Zhidkov et al., 1975) contributed to develop the methodology of the active structures. In order to obtain the comprehension of the earthquakes localization on intraplate zones were used (Campbell, 1978; Jonston, 1989; Johnston and Kanter, 1990; Leonov, 1995; LeRoy and Mauffret, 1996; Liu and Zoback, 1977; Sbar and Sykes, 1973; Stein, 1999; Sykes, 1978; Zoback, 1992). Our main published results about this field are in the table 4.

The three strongest earthquakes in the Wsu and Csu are in table 6 and figure 2. Other 30 earthquakes (Table 7) enabling to sustain the hypothesis of geodynamic cells model because have occurred close to ZS-CHB-JG region. The significant uncertainty of epicentral locations by international networks in other earthquakes appear in table 8.

In table 9 appears some earthquakes associated with the main faults and knots of the Wsu. Also, events in the Gulf of Mexico and the Bahamas regions (Table 10) are related to some of these structures (Cotilla, 1993; 2012; 2016; Cotilla and Franzke, 1999).

Table 4. Location of the Geodynamic Model and Seismotectonic Map

|

Year |

Author (s) |

Figures |

Published |

|

1991 |

Cotilla and Álvarez |

1- SM |

Revista Geofísica, 35 |

|

1993 |

Cotilla |

15- GM and 17-SM |

Phd Thesis |

|

1996 |

Cotilla et al. |

2- SM |

Revista Geofísica, 45 |

|

1998 |

Cotilla |

6- SM |

Revista Física de la Tierra, 10 |

|

1998 |

Cotilla |

1- GM and SM |

Estudios Geológicos, 54(3-4) |

|

1998 |

Cotilla |

4- GM |

Journal of Seismology, 2(4) |

|

1998 |

Cotilla |

2- Initial GM and 8- Improved GM |

Estudios Geológicos, 55(1-2) |

|

1998 |

Cotilla and Álvarez |

3- SM |

Geología Colombiana, 23 |

|

1998 |

Cotilla and Álvarez |

2- SM and 9- SM |

Revista Geofísica, 49 |

|

1999 |

Cotilla and Franzke |

1- SM and 4- GM |

Boletín Geológico y Minero, 110(5) |

|

2001 |

Cotilla and Álvarez |

4- SM and 5- GM |

Revista Geológica de Chile, 28(1) |

|

2007 |

Cotilla et al. |

11- GM |

Russian Geology and Geophysics, 48(6) |

|

2011 |

Cotilla and Córdoba |

5- GM |

Izvestiya, Physics of the Solid Earth, 47(6) |

|

2014 |

Cotilla |

4-SM |

Revista Geofísica, 54 |

Note: GM= Geodynamic model (see Figure 3A); SM= Seismotectonic map (see Figure 2).

The Northern Caribbean (Figure 4) is a good example of the seismotectonic diversity that mainly corresponds to a regional dynamics in a frame of plates’ interaction of different categories. The great majority of the Caribbean earthquakes are associated with the Plate Boundary Zone [PBZ] (Mann and Burke, 1984). The most intense seismicity is located around restraining bends as southeastern Cuba (Table 11) and northern Hispaniola. The largest SA is determined from Hispaniola to Puerto Rico (Cotilla, 2012; Cotilla and Córdoba, 2009; 2011B; Cotilla et al., 1997B; 2007A).

Table 5. Selection of Western and Center Cuban Villages

|

Initial Denomination (Actually) |

Region |

Foundation / First Report |

Distance (km) to Cochinos Bay |

|

La Santísima Trinidad (Trinidad) |

Center |

1514 / 1824 |

125 |

|

Sancti Spíritus (Sancti Spíritus) |

1514 / 1970 |

165 |

|

|

Gloriosa Santa Clara (Santa Clara) |

1689 / 1852 |

130 |

|

|

Matanzas (Matanzas) |

1693 / 1791 |

140 |

|

|

Cienfuegos (Cienfuegos) |

1745 / 1849 |

75 |

|

|

Gibara (Villa Blanca de Gibara) |

1751 / 1914 |

530 |

|

|

Sagua la Grande (Sagua la Grande) |

1812 / 1857 |

135 |

|

|

Agramonte (Agramonte) |

1859 / 1903 |

70 |

|

|

Perico (Perico) |

1879 / 1927 |

85 |

|

|

Corralillo (Corralillo) |

1879 / 1932 |

110 |

|

|

Martí (Martí) |

1879 / - |

95 |

|

|

Varadero (Varadero) |

1883 / 2000 |

130 |

|

|

La Habana (Batabanó) |

Western |

1514 / 1693 |

135 |

|

San Juan de los Remedios (Remedios) |

1515 / 1858 |

170 |

|

|

San Cristóbal de La Habana (Ciudad de La Habana) |

1519 / 1693 |

175 |

|

|

Guane (Guane) |

1600 / 1788 |

300 |

|

|

San Diego de los Baños (San Diego de los Baños) |

1632 / - |

240 |

|

|

Torriente (Torriente) |

1687 / 1932 |

60 |

|

|

Güines (Güines) |

1735 / 1777 |

120 |

|

|

San Cristóbal (San Cristóbal de los Pinos) |

1743 / 1880 |

235 |

|

|

San José de las Lajas (San José de las Lajas) |

1780 / 1995 |

140 |

|

|

Jagüey Grande (Jagüey Grande) |

1850 / 1982 |

55 |

Note: Cuba was discovered in 1492.

The level of ancient seismicity in the Caribbean is up to now highest than of the instrumental period. Cotilla (1998A; B; C; D; 1999A; 2007; 2012; 2014B; C) and Cotilla and Udías (1999B) interpreted it as over estimations and mistakes, where Cuba is not at all an exception. The Caribbean islands have interplate (or plate edge) seismicity but Cuba has also the intraplate type [IPS] (Álvarez et al., 1985; 1990; Cotilla, 1993; 1998A; B; 2014B; Cotilla et al., 1996A; 1997A; B; 1998).

The figure of Cuba island is concave (from SW-NE to NW-SE) as a consequence of the ancient convergence process (Cotilla and Franzke, 1999; Cotilla et al., 1991C; 1996B). Then, the structures located in each of these 2 branches have these strikes. About these ideas will discuss later. Piotowska (1993) found two different tectonic segments in Cuba (Sierra de los Organos and Escambary) but both are genetically related. They are located in the western and center regions, respectively and represent about 10% of the Cuban area (110,911 km2).

Table 6. Largest Earthquakes in Western and Center Seismotectonic Units

|

Nº |

Date |

Isoseismal / Epicenter |

Area (103 km2) |

Coordinates |

Aftershocks |

|

1 |

23.01.1880 |

Yes / Ground |

40 |

22.70 N 83.00 W |

65 |

|

2 |

28.02.1914 |

Yes / Sea |

25 |

21.30 N 76.20 W |

9 |

|

3 |

15.08.1939 |

Yes / Sea |

19 |

22.50 N 79.25 W |

24 |

|

Nº |

M / h (km) |

Fault |

Length (km) |

Rupture (km) |

Locality |

|

1 |

6.2 / 20 |

Guane |

~280 |

58 |

San Cristóbal |

|

2 |

6.2 / 20 |

Nortecubana |

~1,100 |

15 |

Gibara |

|

3 |

5.6 / 15 |

Nortecubana |

~1,100 |

53 |

Remedios |

Seismotectonic Characteristics of Cuba

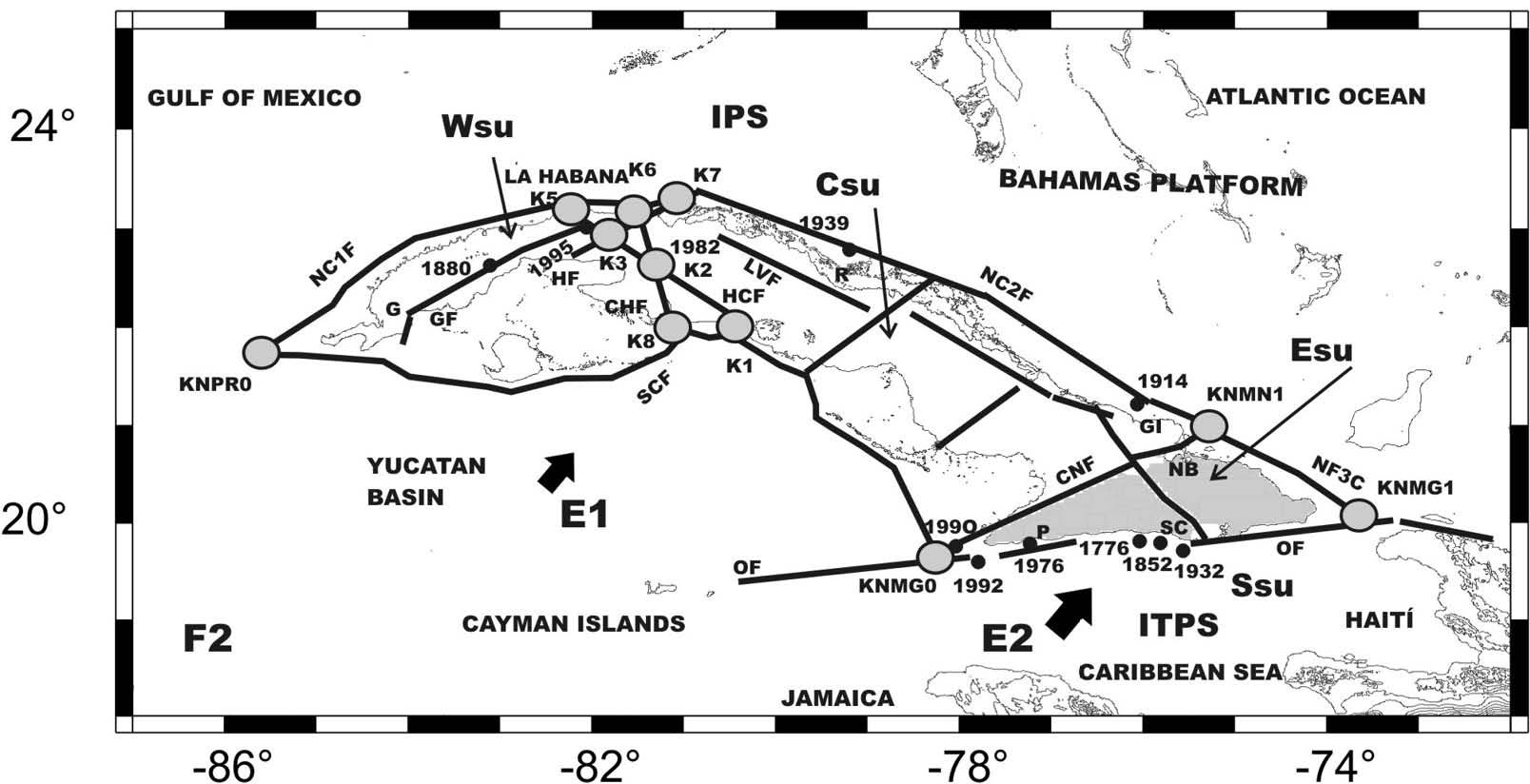

The dynamic interaction between the Caribbean and North American plates is very well reflected in the SA of the Cuban territory (Cotilla, 1993; 1998A; 2014C). This was one of the arguments used for the differentiation of the Cuban Seismotectonic Province into 4 Units (Southeastern [Ssu], Eastern [Esu], Center [Csu] and [Wsu] and to identify 4 main active knots (KNPR0, KNMG0, KNMG1 and KNMN1) (Figure 2) (Cotilla, 2014C; Cotilla et al., 1998). The knots KNMG0 and KNMG1 are in the contact zone [Ssu] of the plates mentioned before through the Oriente fault [OF], where the strongest and most frequent earthquakes take place (Table 12). It is in the PBZ. The other 3 units (Csu, Wsu and Esu) much farther away from the plate contact area, and at an acute hangle caused by the differential influence, demonstrate IPS values (weak and moderate), with periods of occurrence greater than 100 years.

Table 7. Earthquakes Near Jagüey Grande

|

Nº |

Locality |

Earthquakes |

Fault /Knot |

|

1 |

Agramonte |

1903 |

CHF / - |

|

2 |

Caibarién |

15.08.2012 |

NCF / - |

|

3 |

Cienfuegos |

30.08.1846;1914;22.10.2005 |

HCF / K1 |

|

4 |

Corralillo |

1932;09.01.2014 |

NCF / - |

|

5 |

Cumanayagua |

08.08.1996 |

- / K1 |

|

6 |

Girón |

27.03.1964 |

CHF-SCF / K8 |

|

7 |

Güines |

07.07.1777 |

HF-HCF / K3 |

|

8 |

Jaruco |

12.10.1905 |

NCF / - |

|

9 |

Manacas |

15.01.1906 |

- / - |

|

10 |

Manicaragua |

30.07.1943;24.10.1976 |

- / - |

|

11 |

Matanzas |

1812;1854;10.09.1854;1978 |

HF-NCF / K6 |

|

12 |

Perico |

01.1927;05.06.1928 |

CHF / - |

|

13 |

Quemado de Güines |

03.02.1952 |

Las Villas / - |

|

14 |

Rancho Veloz |

05.06.1906 |

Las Villas / - |

|

15 |

Sagua la Grande |

07.07.1857;27.05.1861;27.06.1861; 1886;11.04.1889;14.05.1937; 24.04.1941;04.06.1942;25.05.1960 |

Las Villas / - |

|

16 |

San José de las Lajas |

09.03.1995 |

GF-HCF / K4 |

|

17 |

Torriente |

1982 |

HCF-CHF / K2 |

|

18 |

Varadero |

2000 |

HF-NCF / K7 |

Note: Faults (CHF= Cochinos, GF= Guane, HCF= Habana-Cienfuegos, HF= Hicacos, NCF = Nortecubana, SCF= Surcubana); Knots (K1= Cienfuegos Bay, K2= Torriente-Jagüey Grande, K3= Güines, K4= San de las Lajas, K6 = Matanzas Bay, K7= Hicacos, K8= Cochinos Bay) (see Figure 2).

Table 8. Seismic Data of Corralillo (in 2014)

|

Agency |

Date |

Time |

M |

h (km) |

Coordinates |

|

GEOFON |

09.01 |

20:57:44 |

5.1 |

10 |

23.23 N 80.76 W |

|

USGS |

20:57:43 |

5.1 |

10 |

23.189 N 80.677 W |

|

|

EMSC |

05.02 |

03:19:31 |

4.4 |

14 |

23.25 N 80.69 W |

|

GEOFON |

03:19:38 |

4.4 |

12 |

23.21 N 80.70 W |

|

|

USGS |

03:19:32 |

4.3 |

12 |

23.168 N 80.821 W |

|

|

EMSC |

09.03 |

11:26:18 |

4.8 |

10 |

23.17 N 80.77 W |

|

GEOFON |

11:26:18 |

4.7 |

10 |

23.27 N 80.69 W |

|

|

USGS |

11:26:18 |

4.7 |

09 |

23.183 N 80.751 W |

The neotectonic boundary between Csu and Esu is a 2nd order fault (Cauto-Nipe [CNF]). It has 2 seismoactive knots (KNMGO and KNMN1) at its ends. They connect: 1) OF with CNF in the SW, near to the locality of Cabo Cruz; 2) Nortecubana fault [NCF] with CNF in the NE to the north of Nipe Bay, respectively (Figure 2). The largest level of SA is associated with OF (of 1st order).

Table 9. Faults and Earthquakes of Western Cuba

|

Fault /Acronyms |

Mmax |

Category/ Segments |

Ʃ Knots |

Some Events / (Ʃ Earthquakes) |

|

Cochinos /CHF |

5.0 |

3 / 2 |

2 |

1903;01.1927;05.06.1928;27.03.1964; |

|

Guane /GF |

5.9 |

2 / 3 |

2 |

23.01.1880;31.08.1886;23.09.1921; |

|

Habana-Cienfuegos /HCF |

5.0 |

3 / 4 |

5 |

1693;1810;1835;21.02.1843;08.03.1943;1844;30.08.1846;30.08.1849;1852;1854;04.10.1859;12.1862;25.03.1868;1880; |

|

Hicacos /HF |

3.0 |

3 / 3 |

3 |

1812;05.03.1843;1852;1854;10.09.1854;1880;27.05.1914;1970;27.04.1974;1978; 2000 / (14) |

|

Nortecubana /NCF |

6.2 |

2 / 6 |

6 |

12.08.1873;03.02.1880;28.02.1914;15.08.1939;25.05.1960;24.07.1970;13.05.1978;18.12.1986;05.01.1989;05.01.1990;20.03.1992;24.09.1992; 28.12.1998;2000;09.01.2014 / (>380) |

|

Surcubana /SCF |

5.5 |

3 / 3 |

4 |

1871;1873;1925;1932;1936;23.07.1943;28.07.1943;27.10.1945;26.07.1971; 15.05.1974;27.06.1974;28.08.1974;12.01.1985/ (~50) |

Cuba has 13 active faults (Baconao, Camagüey, Cubitas, La Trocha, Las Villas, Surcubana [SCF], CNF, CHF, GF, HF, HCF, NCF and OF) (Figure 2 and Table 9) (Cotilla, 1993; 2014C). Except OF the others are directly linked with the IPS. The NCF is an active structure that limits by the N to the Cuban megablock. It has a coefficient of sinuosity (ks) value of: 1) 0.74 in the Cabo de San Antonio - Hicacos Penynsula (Varadero) segment (NE strike); 2) 0.94 between Hicacos and Punta de Maisí segment (NW strike) (Cotilla and Udías, 1999A) (Figure 2). These values and strikes indicate the concave figure of this fault that we determined in other structures as the Yucatán Basin (Figure 4). Moreover, the inflections spatially coincide with the geographic meridian of the Mid-Cayman rise spreading center and the deformed SCF near the ZS-CHB (Cotilla and Udías, 1999A).

Table 13 shows the occurrence of earthquakes in 5 time intervals for Wsu. It is significant the quantity of events for the period 1900-1999 and it can be explained as a consequence of the instrumental determinations.

Table 10. Selection of Earthquakes in Bahamas and Gulf of México

|

Nº |

Region |

Date |

M |

|

1 |

Bahamas |

22.02.1992 |

3.2 |

|

2 |

Gulf of México |

07.07.1852 |

7.5 |

|

3 |

06.05.1905 |

- |

|

|

4 |

14.12.2004 |

- |

|

|

5 |

20.12.2004 |

6.6 |

|

|

6 |

10.02.2006 |

5.2 |

|

|

7 |

10.09.2006 |

6.0 |

|

|

8 |

29.10.2009 |

5.5 |

|

|

9 |

26.04.2011 |

5.6 |

|

|

10 |

08.10.2012 |

5.7 |

Table 11. Strongest Earthquakes of the Southeastern Seismotectonic Unit

|

Nº |

Date |

M / I (MSK) / h (km) |

Rupture Estimated (km) |

|

1 |

18.10.1551 |

6.6 / 8 / 15 |

50 |

|

2 |

11.02.1678 |

6.75 / 8 / 30 |

55 |

|

3 |

11.06.1766 |

6.8 / 9 / 25 |

85 |

|

4 |

07.07.1842 |

6.8 / 8 / 30 |

77 |

|

5 |

20.08.1852 |

6.4 / 8 / 30 |

75 |

|

6 |

03.02.1932 |

6.75 / 8 / 35-40 |

65 |

|

7 |

07.08.1947 |

6.7 / 7 / 30 |

49 |

|

8 |

19.02.1976 |

5.7 / 8 / 15 |

55 |

|

9 |

26.08.1990 |

5.9 / 8 / 10 |

60 |

|

10 |

25.05.1992 |

6.9 / 15 / 23 |

65 |

|

11 |

04.02.2007 |

6.2 / 15 / 10 |

50 |

Álvarez et al. (1985; 1990) and Cotilla (1993) studied epicenter and hypocenter determinations made by the international agencies and the Cuban local seismic stations. From the beginning and until the 1980s the determinations were inaccurate and very vague. This was mainly exemplified with two earthquakes: 1) 19.02.1976 (Ms= 5.7) in Pilón, Ssu; 2) 16.12.1982 (Ms= 5.0) in Torriente-JG, Wsu (Figure 2). It is well known that the seismic devices and the development of software’s have improvement of the accurracy determinations. But it is still insufficient for the events of low energy that occur in the Wsu (Tables 3 and 8). An alternative used in Cuba for the study of such type of seismicity has been developing geodynamic cells models. Then, for the Western and Eastern macroregions were related some active faults (Table 9) and their intersections or knots (Table 14) with the stress concentration, mainly, from the interaction of Caribbean-North American plates.

We consider that in the Cuban seismotectonic province the NCF has a 2nd order category, with 2 levels: 1) Category 2A (Cabo de San Antonio-La Habana; W of Hicacos Penynsula (Varadero)-La Trocha; and Nipe-Punta de Maisí); 2) Category 2B (La Habana-Hicacos Penynsula; and La Trocha-Nipe) (Figure 2). But, according to the strike and setup of the NCF three segments are determined: 1) West= NC1F (Cabo de San Antonio-Hicacos Penynsula); 2) Center= NC2F (Hicacos Penynsula-Nipe Bay); 3) East= NC3F (Nipe Bay-Punta de Maisí). The length of each segment is different, being the shortest, the third structure that is the closest to the PBZ (NC3F), and very near to Bahamas Platform and the Atlantic Ocean. Here is joint in the knot KNMG1 with the OF and the Septentrional fault (N of Hispaniola) (Figure 2). The other two segments have some differences. The NC1F is adjacent to the Gulf of México where the knot KNPRO appear, while the NC2F adjoins the narrowest part of the Bahamas Platform. Each segment is associated with earthquakes in the historical and instrumental periods (i.e.: 1) Western region: earthquakes’ series of 1981; 2) Center region: 28.02.1914 and 15.08.1939; 3) Eastern region: 05.01.1990, 20.03.1992, 24.09.1992 and 28.12.1998). The NCF has the SA: 1) strongest in the NC2F Remedios-Caibarién and Gibara segment; 2) lowest in the westernmost segment, NC1F.

Table 12. Characteristics of the Cuban Seismogenic Zones

|

Type of Sesimicity |

||

|

Characteristics |

Interplate |

Intraplate |

|

Area of perceptibility (103 km2) |

110 |

40 |

|

Associated fault (s) |

OF |

BF, CF, CHF, CNF, CUF, GF, HCF, HF, LTF, LVF, NCF, SCF |

|

Depth (km) |

30 |

15 |

|

Distance between strong earthquakes (km) |

100 |

825 |

|

Distance of perceptibility (km) |

~800 |

~300 |

|

Earthquakes (%) |

~75 |

<25 |

|

Epicenter (in) |

Sea |

Land and Sea |

|

Fatalities |

>100 |

~20 |

|

First report |

Cabo Cruz-1551 |

Baracoa-1528 |

|

Imax (MSK) |

9 |

8 |

|

Isoseismals |

Middle |

Complete and middle |

|

Mmax / hmax (km) |

6.8 / 60 |

6.2 / 20 |

|

M (interval / earthquakes) |

6.8-6.0 / 6; 5.9-5.0 / 18 |

6.2-6.0 / 2; 5.9-5.0 / 3 |

|

Repetition period (years) |

~80 |

>100 |

|

Rupture estimatated (km) |

85 |

58 |

Note: Faults (BF= Baconao, CF= Camagüey, CHF = Cochinos, CNF= Cauto-Nipe, CUF= Cubitas, GF= Guane, HCF= Habana-Cienfuegos, HF= Hicacos, LTF= La Trocha, LVF= Las Villas, NCF= Nortecubana, OF= Oriente, SCF= Surcubana) (see Figures 2 and 4).

Figure 3B shows four areas with the main seismoactivity in Cuba. There are represented by 4 ellipses in color graduation, from greatest to lowest (1= Southeastern, 2.1= Guane, 2.2= Remedios, 2.3= Gibara, 3.1= Cochinos-Corralillo, 3.2= Nipe-Maisí, and 4= Surcubana). It can be considered as a roof seismotectonic regionalization (Cotilla and Córdoba, 2007).

Table 13. Some Data of the Western Cuban Earthquake Catalog

|

Time Period |

Events |

Mmax / Mmín |

hmax / hmín (km) |

With Full Date |

|

1492-1699 |

3 |

5.0 / 2.6 |

30 / - |

- |

|

1700-1799 |

4 |

3.7 / 3.1 |

10 / - |

2 |

|

1800-1899 |

35 |

6.2 / 2.5 |

20 / 10 |

24 |

|

1900-1999 |

862 |

6.2 / 1.0 |

88 / 12 |

758 |

|

2000-2013 |

11 |

4.4 / 1.9 |

33 / 10 |

6 |

|

Ʃ =921 |

Ʃ =790 |

Seismotectonic Models

Cotilla and Franzke (1994) calculated, for first time, a stress tensor for Esu. Cotilla et al. (1998; 2007B) subsequently identified a regional stress tensor for Cuba with NE-SW striking. These led us to consider the existence of normal and left-lateral strike-slip faults, with small pull-apart basins, fault ridges, and push-up and flower structures. We also identified different segments in the Cuban faults that could explain the existing low earthquake magnitudes in the Csu and Wsu (Tables 12 and 13).

The Wsu has a structure of faulting and uneven blocks, with different degrees of mobility and a tendency to vertical displacement. However, they are interrelated (due to processes not yet understood) in a regional context where left-lateral strike-slip is predominant. Blocks show a mix of vertical movement, rotation and tilting. The Wsu has 8 blocks or cells (CI= East Matanzas, CII= Center Matanzas, CIII= Habana-Matanzas, CIV= La Habana, CV= West Habana, CVI= South Habana, CVII= Zapata-Cochinos and CVIII= Cienfuegos) (Cotilla, 2014B) (Figure 3A). These cells are made up of the following active faults: CHF, GF, HF, HCF, NCF and SCF. The majority of faults was linked to earthquakes (Figure 2 and Table 9). We also found 8 knots where the fault intersections are located or associated with some earthquakes (Table 14). The model of the Wsu includes 4 administrative provinces (Pinar del Río, Ciudad de La Habana, La Habana, and Matanzas) (Figure 5 of Cotilla and álvarez, 2001).

The HCF is a large lineal SE-NW structure (~230 km long) of the Wsu. In both extremes (NW and SE) are the La Habana Bay (K5) and Cienfuegos Bay (K1), respectively. The mentioned before 1982 earthquake that hit Torriente-JG localities (Figures 2 and 3, Tables 2 and 9) is associated at the intersection of HCF with CHF (knot K2). In 1995 another earthquake was registered (Ms= 2.5) and it was felt at Pedro Pí (PP), in the region of San José de Lajas, La Habana (Figure 3A, Tables 1 and 9). This event also took place on the HCF, but farther to the NW, where it is another intersection of the HCF with GF (knot K4). The isoseismal map by González et al. (1995) showed that the main perceptibility was toward the NW. Thus, the earthquakes in Torriente-JG and PP localities may support the idea that earthquakes in Wnu take place at the intersections of different active structures (Cotilla, 1995) (Figure 3A). Similar proposals in other places were previously published by various authors such as (Guelfand et al., 1976; Gvshiani et al., 1987; Zhidkov, 1985). We believe that this favors block composition, block rotation, and the stress transmission, with the resulting seismic energy release.

From instrumental data, the Mmax in Torriente-JG is 5; while in the immediate zones is bounded by values of 5.1 (Corralillo, associated with the NC2F), 5.0 (Varadero; with NC2F and HF) and 4.1 (CZ-BCH with SCF and CHF). All these values shows the validity of the seismic intensity maps of Álvarez et al. (1985; 1990) (Figure 1). Also, they indicate: 1) the low intensity values in the region; 2) the magnitude values estimated on the seismotectonic map are suitable (Cotilla et al., 1991A); 3) the seimogenetic layer is less than 20 km (Cotilla, 1993; Cotilla et al., 1996B).

Cotilla and Álvarez (2001) (see their Figure 7) suggested to the Wsu that 4 pairs of faults (1) GF and HCF; 2) HF and HCF; 3) HF and NCF; 5) HCF and CHF) are interconnected active structures. Also, the strike, geometry and activity of these faults can be explained by the presence of 2 large depressed oceanic structures, the Gulf of México and the Yucatán Basin (Figure 2), which are opposed in the contemporary tectonic stress field, mainly caused by the Caribbean, Cocos and North American plates interactions. There is a similar explanation to the SA in the Eastern Gulf of México. In it 2 earthquakes occurred (10.02.2006 and 10.09.2006). The second one has a mixed type focal mechanism with a fault plane of ~300º (NW-SE). This strike coincides with the NCF and the epicenters are ~600 km from Ciudad de La Habana. Cotilla (2014B) reached the same conclusion based on seismicity and tectonic data of the Gulf of México (Froehlich, 1982; LeRoy, 1998).

Table 14. Some Data of the Main Knots of Western Cuba

|

Knots |

|||||||||

|

Nº |

Characteristics |

K1 |

K2 |

K3 |

K4 |

K5 |

K6 |

K7 |

K8 |

|

1 |

Events/Imax |

3/5 |

7/5 |

1/5 |

3/5 |

18/5 |

4/5 |

1/6 |

5/4 |

|

2 |

Category: |

||||||||

|

A |

Disruptive |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

B |

Fault |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

C |

Morphostructural |

1 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

|

D |

Neotectonic |

1 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

E |

Seismogenetic |

1 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

Note: K1= Cienfuegos Bay, K2= Torriente-Jagüey Grande, K3= Güines, K4= San José de las Lajas, K5= Ciudad de La Habana, K6= Matanzas Bay, K7= Hicacos, K8= Cochinos Bay.

We can assume that the occurrence of strong earthquakes in 3 localities of the Wsu and Csu regions (1) San Cristóbal (135 years), 2) Gibara (101 years), and 3) Remedios (76 years)) is a consequence of a same seismotectonic process of IPS type. Nevertheless, they are not associated with the seismotectonic of the JG-ZS- Cochinos Bay region. The SA of knots has a decreasing order: K5, K2, K8, K6, K1, K4, K3 and K7.

Discussion and Conclusions

The CHB-JG-Cárdenas area is very well defined from: 1) morphostructural scheme (González et al., 2003), 2) neotectonic scheme and map (Cotilla et al., 1991C; González et al., 1989). This area differs from others located along the E and W sides, where the trends of uplifting values are higher, also the SA is also greater (Cotilla et al., 1996B).

The northern Cuban (Cárdenas-Corralillo-Sagua la Grande) limit with the CHB-JG area. It has a very well defined spatial relationship with the seismogenic zone of Las Villas fault (3rd order) (Figure 2). This structure is parallel to the NC2F and it shows SA in Cárdenas, Corralillo, Sagua La Grande and Remedios.

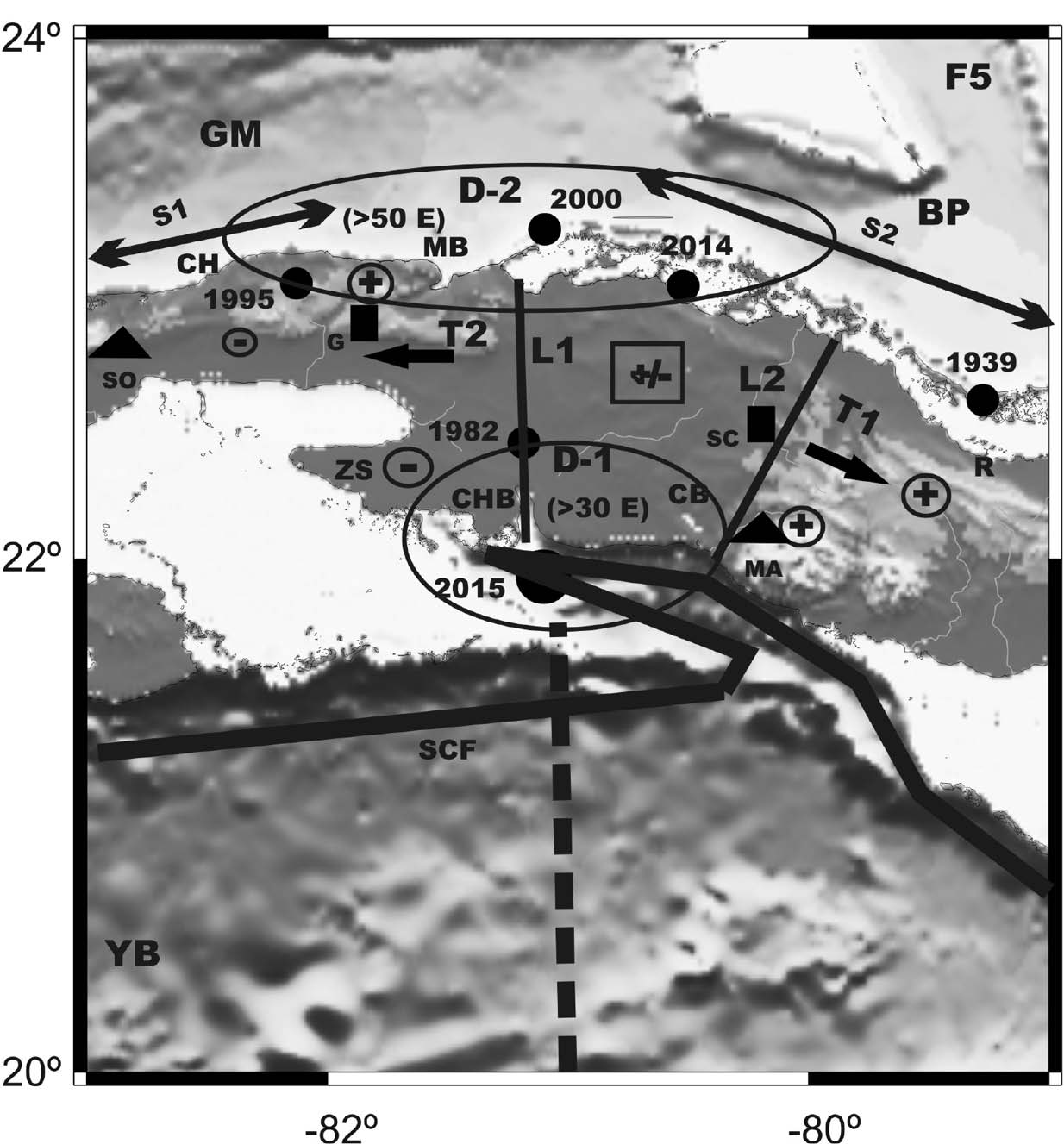

The territory located to the E of the Matanzas Bay up to Corralillo (north coast), and between the Cienfuegos Bay and ZS (south coast), is defined into two S-N profiles: 1) CHB-Cárdenas (L1); 2) Cienfuegos Bay-Sierra Morena and Corralillo (L2) (Figure 5). This area is composed by a broad ordered set of 5 low flat karstic plains (Cotilla and Córdoba, 2010; González et al., 2003). It is defined as a mesoblock with null or very weak trend of uplifting (Cotilla et al., 1991C; González et al., 1989). From a tectonic point of view, the Santo Domingo basin, is mainly defined here from Cárdenas to Morón localities. That means, the region was influenced by two type of extensional tensors to the: 1) SE (T1, E of the Cienfuegos Bay); 2) SW-W (T2, W of the Matanzas Bay) (Figure 5).

The mentioned before region has a pull-apart basin which we call JG. Here we found a clear spatial contrast of blocks with different figures and trends (null, weak and moderate) of vertical movements. The blocks with weak uplifting tendency are located at the N and S borders. From the northern side there are four uplifting blocks (CII, CIII, CIV and Las Villas), while there are two in the southern one (CVIII and Guaniguanico). The CVIII cell is distinguished by three knots (K1, K2 and K8) with 3, 7 and 5 earthquakes, respectively. The donwtrow blocks are CI, CVI and CVII.

Following the proposals by Cotilla and Franzke (1999), Cotilla and Udías (1999A) and Cotilla et al. (1996B; 1997B; 1998) the stress transmission is easier northward in the Remedios-Caibarién-Gibara (NC2F) segment than in the Cabo de San Antonio-Hicacos Penynsula (NC1F) (Figure 2). These two segments also belong to the Wsu and they are related to strong earthquakes. The energy released by strong and weak earthquakes also occurs at the northern edge of the megablock, in the NCF, but in its Center and Eastern parts. Weak earthquakes occur inside the island, where the following faults are located: Baconao, Camagüey, Cubitas, Las Villas, La Trocha, Santa Clara, Tuinicú, and HC (Cotilla, 1993). Strong and weak earthquakes only occur in the GF and weak earthquakes take place in the NC1F. We consider that the stress transmission comes from the two mentioned parts of the plate boundary (Swan [SWF] and OF) (Figure 4). The energy transmission takes place through two different structures: 1) the South Platform of Cuba; 2) the Yucatán Basin, respectively. The Yucatan Basin has records from the Late Cretaceous to the Paleogene affected by the Neogene strike-slip in the Caribbean-North American region. Also, the distances are different: 1) SWF-NC1F= ~430 km; 2) OF-NC3F= ~300 km.

The influence of the lithospheric plates interaction produces two seismotectonic deformation zones in La Habana-Las Villas segment. They have different figures and areas in the south (D-1) and the north (D-2) (Figure 5). The quantity of earthquakes also differs: D-1 (> 30) and D-2 (> 50). The Mmax (5.1) is in D-2.

According to the spatial distribution of perceptiblity, outlined in the Introduction, we can assume an energy radiation pattern in a semicircular shape with center in BCH. Also, from the data of the tables 7, 9, 13 and 14 we can say that 32, 100, 921 and 41, respectively, earthquakes have occurred in several towns of Wsu. Then, the region is active because a lot of earthquakes have occurred on it. Taking into the account the 21.01.2015 earthquake data: 1) the epicenters determinations differences (Table 3); 2) the non-existence of known faults in the ZS. The knot K8, Cochinos Bay, is the most probably place to the epicenter. It is directly related with 2 geodynamic cells (CVII (8 earthquakes) and CVIII (15 earthquakes)). Both structures are included in the southern seismotectonic deformed area (D-1) where CHF and SCF are determined.

Figura 5. Pull-Apart Basin Model (Jagüey Grande)

Appear: A) Black arrows= Stress (T1, T2); B) Black circle= epicenter (year= 1982); C) Black discontinue line= Meridiam of the Mid-Cayman rise spreading centre; D) Black line with arrows= Main strike of the coast line (S1= West, S2=Center-East); E) Black line= Fault (SCF= Surcubana); F) Seismotectonic deformed areas (D-1 and D-2); G) Geographic area (BP= Bahamas Platform, GM= Gulf of México, YB= Yucatan Basin); H) Heavy black lines= limits of the region (L1, L2); I) Localities (CB= Cienfuegos Bay, MB= Matanzas Bay, CH= Ciudad de La Habana, ZS= Zapata Swamp, R= Remedios); J) Sense of: uplitf (+), downtrow (-), nule (+/-); K) Black triangle= seismic station (SO= Soroa, and MA= Manicaragua); L) Black square= Proposal of seismic station (G= Güines, and SC= Santa Clara).

Stronger earthquakes of the Wsu and Csu (1914 (6.2) Gibara, 1939 (5.6) Remedios and 2014 (5.1) Corralillo) have occurred in the S2 branch (Figure 5). They are probably related to seismoactive NC2F, which interacts directly with the Bahamas Platform. While the higher level of SA occurs in the southern part of these same units in BCH-Cienfuegos-Trinidad; although their values are lower than in the Northern segment. This situation is reversed for the Esu and Ssu where the greatest SA is in the south (Cabo Cruz-Pilón-Santiago de Cuba-Punta de Maisí) associated to OF. Cotilla (1993) explained it by the direct interaction of these 2 units with the Caribbean plate. In the northern part is the NC3F, that relates to the Atlantic Ocean. While in the westernmost part of the Wsu the greater SA is associated with GF, but never with NC1F. The latter one directly interacts with the Gulf of México.

Sykes (1978) observed that IPS areas are located throughout pre-existing tectonic weakness zones. The GF and HCF are examples of it (Cotilla et al., 2007B). Zoback (1992) showed that horizontal compressional stresses can be transmitted over great distances through the continental and oceanic lithospheres. Also, Van der Pluijm et al. (1997) suggested that continental interiors registering plate tectonic activity and intraplate fault reactivation (and earthquake triggering). It is mainly dependent on the orientation of fault zones relative to the plate margin. The deformation of continental interiors can be represented by relatively simple rheological models. Using these mentioned authors and the results of (Johnston and Kanter, 1990; Liu and Zoback, 1977; Sbar and Sykes, 1973; Stein, 1999) we can say that: 1) the tectonic forces of the plate margins can be transmitted inside the plates for up to distances of 2,000 km; 2) the status of the forces in the interior continental zone seems to be relatively independent of the immediate surroundings, as well as of the previous tectonic style; 3) there is a predominance of transmission of energy from the borders toward the interior of the plate; 4) intraplate seismic events occur in areas where the crust has been weakened by previous activity. Therefore, if we apply these arguments to Wsu we can conclude that earthquakes have and do take place in this Cuban unit.

We believe that to improve the detection of events in the Wsu and Csu it is necessary to install at least two stable seismic stations in: 1) Güines and 2) Santa Clara (Figure 5). With that network (Soroa, Güines, Santa Clara and Manicaragua stations) would be cover almost 90% (M> 4.0) of these units. In addition, there would be a better understanding of the natural and induced SA (by the oil Geophysical Exploration of the Northern Sea area). These stations would be located in same amount of cells (CV, CIII, CI and CVIII) or different blocks.

We conclude that in the Wsu: 1) the mentioned faults (CHF, GF, HF, HCF, NCF and SCF) are actives (Table 9); 2) the tectonic mechanism of intraplate readjustments through faults and block rotations are responsible for at least 5 earthquakes (1) 1880 in San Cristóbal (Pinar del Río) [23]; 2) 1982 in Torriente-JG (Matanzas); 3) 1995 PP (San José de las Lajas, La Habana); 4) 2000 in Varadero (Hicacos Penynsula); 5) 21.01.2015 (mb= 4.1 / h= 16 km / 22.216 N 81.422 W) in the surrounding of de ZS-CHB (Matanzas) where is the knot K8 (made up CHF and SCF)); 3) the earthquakes can be explained by the transpression process of the Caribbean and North American plates at the SWF and OF zones, and the consequent stress transfer toward the Cuban Seismotectonic Province.

Acknowledgements

Amador García Sarduy prepared all figures. Funding by TSUJAL (CGL2011-29474-C02-01) and GR35/10-A/910549 projects are gratefully acknowledged. José Leonardo Álvarez Gómez, Enio César González Clemente, Peter Bankwitz ϯ, Joachim Pilarski and Hans-Joachim Franzke supported the original idea of the faults’ knots to the Cuban region.

References

Álvarez L., Cotilla M. and Chuy T. Informe final del tema 430.03: Sismicidad de Cuba. In: Archivo del Departamento de Sismología, Instituto de Geofísica y Astronomía, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba, 1990.

Álvarez L., Rubio M., Chuy T. and Cotilla M. Informe final del tema de investigación 31001: Estudio de la sismicidad de la región del Caribe y estimación preliminar de la peligrosidad sísmica en Cuba. In: Archivo del Departamento de Sismología, Instituto de Geofísica y Astronomía, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba, 1985.

Assinovskaya B.A. and Soloviev S.L. (1994). Definition and description of the zones of potential earthquake sources in the Barents Sea. Izv.Phys. Solid Earth, 29(8), 664-675.

Backmanov D.M. and Rasskazov A.A. (2000). Recent faults in the junction área between the southern and central Urals. Geotectonics, 4, 25-31.

Campbell D.L. (1978). Investigation of the stress concentration mechanism for intraplate earthquakes. Geophys.Res.Lett., 5, 477-479.

Chuy T., Vorobiova E., González B., Álvarez L., Pérez E., Serrano M., Cotilla M. and Portuondo O. (1983). El sismo del 16 de diciembre de 1982. Torriente-Jagüey Grande. Revista Investigaciones Sismológicas en Cuba, 3, 43 p.

Cotilla M.O. (2016). The Guane fault, western Cuba. Revista Geográfica de América Central, 57, ---.

Cotilla M.O. y Córdoba D. (2015). Guantánamo neo-estructura atípica del Caribe norte. Revista Investigaciones Geográficas de Chile, 50, 51-88.

Cotilla M.O. (2014A). Alternative interpretation for the active zones of Cuba. Geotectonics, 48(6), 459-482.

Cotilla M.O. (2014B). Sismicidad de interior de placa en Cuba. Revista Geofísica, 54, 93-125.

Cotilla M.O. (2014C). Cuban Seismology. Revista de Historia de América, 143, 43-98.

Cotilla M.O. (2012). Historia sobre la Sismología del Caribe Septentrional. Revista de Historia de América, 147, 111-154.

Cotilla M.O. Un recorrido por la Sismología de Cuba. Editorial Complutense, Madrid, 2007, ISBN 97-8-47- 491827-4.

Cotilla M.O. (1999ª). La ciencia sismológica en Cuba (I). Consideraciones principales. Revista de Historia de América, 124, 29-54.

Cotilla M.O. (1999B). El controvertido alineamiento Habana-Cienfuegos, Cuba. Estudios Geológicos, 55(1-2), 67-88.

Cotilla M.O. (1998A). Una revisión de los estudios sismotectónicos en Cuba. Revista Estudios Geológicos, 54(3-4), 129-145.

Cotilla M.O. (1998). Sismicidad y sismotectónica de Cuba. Revista Física de la Tierra, 10, 53-86.

Cotilla M.O. (1998C). Terremotos de Cuba. GEOS, 18(3), 180-188.

Cotilla M.O. (1998D). An overview on the seismicity of Cuba. Journal of Seismology, 2, 323-335.

Cotilla M.O. (1995). El sismo del 09.03.1995 en Ganuza, San José de las Lajas. Informe del Instituto de Geofísica y Astronomía, Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente, de Cuba, 10 p.

Cotilla M.O. (1993). Una caracterización sismotectónica de Cuba. PhD Thesis, Instituto de Geofísica y Astronomía, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba, 200 p.

Cotilla M.O. and Álvarez J.L. (2001). Regularidades sismogenéticas de la unidad neotectónica Occidental de Cuba. Revista Geológica de Chile, 28(1), 3-24.

Cotilla M.O. and Álvarez J.L. (1999). Mapa de zonas sismogeneradoras de Cuba. Geología Colombiana, 23, 97-106.

Cotilla M.O. and Álvarez J.L. (1998). Esquema de regionalización del potencial de amenaza geológica en Cuba. Revista Geofísica, 49, 47-86.

Cotilla M.O. and Álvarez J.L. (1991). Principios del mapa sismotectónico de Cuba. Revista Geofísica, 35, 113-124.

Cotilla M.O. and Córdoba D. (2011A). Study of the earthquake of the January 23, 1880, in San Cristóbal, Cuba and the Guane fault. Izv.Phys. Solid Earth, 47(6), 496-518.

Cotilla M.O. and Córdoba D. (2011B). Análisis morfotectónico de la isla de Puerto Rico, Caribe. Revista Geofísica, 52, 79-126.

Cotilla M.O. and Córdoba D. (2010). Study of the Cuban fractures. Geotectonics, 44(2), 176-202.

Cotilla M.O. and Córdoba D. (2009). Morphostructural analysis of Jamaica. Geotectonics, 43(5), 420-431.

Cotilla M.O. and Córdoba D. (2007). A morphotectonic study of the Central System, Iberian Península. Russian Geology and Geophysics, 48(4), 378-387.

Cotilla M.O. and Franzke H.J. (1999). Validación del mapa sismotectónico de Cuba. Boletín Geológico y Minero, 110(5), 573-580.

Cotilla M.O. and Franzke H.J. (1994). Some comments on the seismotectonic activity of Cuba. Z.Geol.Wiss., 22(3-4), 347-352.

Cotilla M.O. and Udías A. (1999A). Geodinámica del límite Caribe-Norteamérica. Rev.Soc.Geol. de España, 12(2), 175-186.

Cotilla M.O. and Udías A. (1999B). La ciencia sismológica en Cuba (II). Algunos terremotos históricos. Revista de Historia de América, 125, 45-90.

Cotilla M.O., Álvarez L. and Rubio M. (1997A). Sismicidad de tipo intermedio en Cuba. Revista Geología Colombiana, 22, 35-40.

Cotilla M.O., Córdoba D. and Calzadilla Mª. (2007A) Morphotectonic study of Hispaniola. Geotectonics, 41(5), 368-391.

Cotilla M.O., Franzke H.J. and Córdoba D. (2007B). Seismicity and seismoactive faults of Cuba. Russian Geology and Geophysics, 48, 505-522.

Cotilla M.O., Álvarez L., Chuy T. and Portuondo O. (1988). Algunos criterios de la peligrosidad sísmica en Cuba (2). Algunos criterios sobre la peligrosidad sísmica en zonas de baja actividad del territorio de Cuba. Comunicaciones Científicas sobre Geofísica y Astronomía, 2, 19 p.

Cotilla M.O., Bankwitz P., Álvarez L., Franzke H.J., Rubio M.F. and Pilarski J. (1998). Cinemática neotectónica de Cuba. Rev.Soc.Geol. de España, 11(1-2), 33-42.

Cotilla M.O., Bankwitz P., Franzke H.J., Álvarez L., González E., Díaz J.L., Grünthal G., Pilarski J. and Arteaga F. (1991A). Mapa sismotectónico de Cuba, escala 1:1,000,000. Comunicaciones Científicas sobre Geofísica y Astronomía, 23, 35 p.

Cotilla M.O., Bankwitz P., Franzke H.J., Álvarez J.L., González E.C., Díaz J.L. and Arteaga F. (1996A). Una valoración sismotectónica de Cuba. Revista Geofísica, 45, 145-180.

Cotilla M.O., Franzke H.J., Pilarski J., Portuondo O., Pilarski M. and Arteaga F. (1991B). Mapa de alineamientos y nudos tectónicos principales de Cuba, escala 1:1,000,000. Revista Geofísica, 35, 53-112.

Cotilla M.O., González E.C., Franzke H.J., Díaz J.L., Arteaga F. and Álvarez L. (1991C). Mapa neotectónico de Cuba, escala 1:1,000,000. Comunicaciones Científicas sobre Geofísica y Astronomía, 22, 37 p.

Cotilla M.O., Millán G., Álvarez L., González D., Pacheco M. and Arteaga F. (1996B). Esquema neotectogénico de Cuba. Informe científico-técnico del Departamento de Geofísica del Interior, 100 p. In: Archivo del Instituto de Geofísica y Astronomía, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba.

Cotilla M.O., Rubio M., Álvarez L. and Grünthal G. (1997B). Potenciales sísmicos del sector Centro-Occidental del arco de las Antillas Mayores. Revista Geofísica, 46, 129-150.

Froehlich C. (1982). Seismicity of the Central Gulf of Mexico. Geology, 10, 103-106.

González E.C., Cañete C.C., Díaz J.L., Pérez L. and Cotilla M.O. (1989). Esquema morfoestructural de Cuba, escala 1:250,000. Revista Geología y Minería, 1, 16-34.

González E.C., Cotilla M.O., Cañete C.C., Díaz J.L., Carral R. and Arteaga F. (2003). Estudio morfoestructural de Cuba. Geogr.Fis.Dinam.Quat., 26(1), 49-70.

González B.E., Álvarez J., Serrano M., García J., Rodríguez V., Pérez L. and Fernández E. Informe científico-técnico del 9 de marzo de 1995: Ganuza, Municipio San José de las Lajas. In: Archivo del Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Sismológicas, Filial Occidental. Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente de Cuba, 13 p., 1995.

Guelfand I.M., Guberman S.A., Keylis-Borok V.I., Knopoff L., Press F.S., Rantsman E.Y., Rotvain I.M. and Skii A.M. (1976). Condiciones de surgimiento de terremotos fuertes (California y otras regiones). Vichislitielnaya Seismologiya, 9, 3-91.

Gvshiani A.D., Gorshkov A., Kosobokov V., Cisternas A., Philip H. and Weber C. (1987). Identification of seismically dangerous zones in the Pyreness. Annales Geophysicae, 87, 681-690.

Johnston A. The seismicity of stable continental stable interiors. In: Earthquakes at North Atlantic Passive Margins. Neotectonics and Postglacial Resound, 299-327 pp. (Eds. S. Gregersen and W. Bashan), 1989.

Johnston A.E. and Kanter L.R. (1990). Earthquakes in stable continental crust. Sci.Am., 262(3), 68-75.

Leonov Yu.G. (1995). Esfuerzos en la litosfera y geodinámica de interior de placa. Geotectonika, 6, 3-22.

LeRoy S.D. (1998). Treating the Gulf of Mexico as a continental margin petroleum province. The Leading Edge, 209-212.

LeRoy S.D. and Mauffret A. (1996). Intraplate deformation in the Caribbean region. J.Geology, 21(1), 113-122.

Liu L. and Zoback M.D. (1977). Lithospheric strenghts and intraplate seismicity in the New Madrid seismic zone. Tectonics, 16, 585-595.

Mackey K.G., Fiyita K., Gunbina L.V., et al. (1977). Seismicity of the Bering Strait region: Evidence for Bering block. Geology, 25, 979-982.

Makarov G.V. and Schukin Y.K. (1976). Valoración de la actividad de las fallas ocultas. Geotektonika, 1, 96-109.

Mann P. and Burke K. (1984). Neotectonics of the Caribbean. Rev.Geophys. Space Phys., 22, 309-362.

Piotrowska K. (1993). Interrelationship of the terranes in western and central Cuba. Tectonophysics, 230, 273-282.

Sbar L. and Sykes L.R. (1973). Contemporary compressive stress and seismicity in Eastern North America: An example of intraplate tectonics. Geol.Soc.Am.Bull., 84, 1,861-1,882.

Sherman S.I. and San’kov V.A. (2010). Faulting and seismicity: Discussion of topical interdisciplinary. Izv.Phys. Solid Earth, 46(4), 364-366.

Sibson R.H. (1985). A note on fault reactivation. J.Struct.Geol., 7, 751-754.

Spiridonov N. and Grigorova E. (1980). On the interrelation between seismicity and fault structure identified by space image interpretation. Space Res. Bulgaria, 3, 42-46.

Stein R.S. (1999). The role of stress transfer in earthquake occurrence. Nature, 402, 605-609.

Stein R.S. and Yeats R.S. (1989). Hidden earthquakes. Science, 260, 48-57.

Sykes L.R. (1978). Intraplate seismicity reactivation of preexisting zones of weakness, alkaline magmatism and tectonic postdating continental fragmentation. Rev.Geophys. Space Phys., 16(4), 621-688.

Van der Plujim B.A., Craddock J.P., Graham B.R. and Harris J.H. (1997). Paleostress in cratonic North-America: Implications for deformation of continental interiors. Science, 277, 794-796.

Zhidkov M.P. (1985). Morfoestructuras de las zonas de sistemas continentales-oceánicas del cinturón pacífico en relación con el pronóstico de los lugares de fuertes terremotos (Kamchatka-occidente de Sudamérica). Resumen Ampliado, Phd Thesis). In: Instituto de Geografía de la A.C. de la URSS, Moscú, 1985.

Zhidkov M.P., Rotvain I.M. and Sadowskii A.M. (1975). Forecast of more probable sites for earthquake occurrences. Multiple interceptions of lineaments in the Armenian area. Vichislitielnaya Seismologiya, 8, 53-70.

Zoback M.L., 1992. First- and second- order patterns of stress in the lithosphere: The World stress map project. J.Geophys.Res., 97, 11,703-11,728.

1 Doctor en Ciencias Física, y Profesor del Departamento de Geofísica y Meteorología, Facultad de Ciencias Físicas. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Ciudad Universitaria, 28040 Madrid. macot@ucm.es

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional.