Número 69(2) • Julio-diciembre 2022

ISSN: 1011-484X • e-ISSN 2215-2563

Doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.15359/rgac.69-2.2

Recibido: 31/7/2021 • Aceptado: 8/10/2021

URL: www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/geografica/

Licencia (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Áreas verdes urbanas, una caracterización paisajística y biológica aplicada a una microcuenca de la Gran Área Metropolitana de Costa Rica

Green Urban Areas, a Landscape and Biological Characterization Applied to a Micro-basin of the Great Metropolitan Area of Costa Rica

Marilyn Romero-Vargas1

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Tania Bermúdez-Rojas2

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Alejandro Durán-Apuy3

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Marvin Alfaro-Sánchez4

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Sebastián Bonilla-Soto5

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Abstract

This article presents a landscape and biological characterization of urban green areas (UGA) of the Bermudez River micro-basin located in the province of Heredia, Costa Rica. This characterization is based on a classification according to criteria for the use of these green spaces, where landscape attributes such as quantity, average size, total area and condition of land cover are described; and biological attributes such as richness of species, genera and families, percentages of exotic and native species are identified by UGA category. Geospatial data was used in the case of the landscape component, obtained from municipalities, as well as photointerpretation and generation of own cartography. For assessing the biological component, field samplings, consultation with experts, and secondary sources through an exhaustive review of scientific literature and of online databases was employed. The results show that 8.95% (664.68 ha) of the total UGAs present in the micro-basin is dedicated to biodiversity conservation, protection of water resources and recreation, while private UGAs destined to crops and pastures almost quadruple the former (31.33%; 2,325.81 ha). 1,029 species of trees, shrubs, herbs, climbing plants, etc. were identified, with gardens and streets contributing the most species. Vertebrate fauna is dominated by birds, followed by reptiles, amphibians and finally mammals. In conclusion, the UGAs present in the study area show significant landscape and biological differences in terms of quantity, size, spatial distribution, floristic and fauna richness, and UGAs form a green web that provides ecosystem services to the city.

Keywords: Urban green areas, floristic wealth, urban fauna, Bermúdez river, landscape.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta una caracterización paisajística y biológica de las áreas verdes urbanas (AVU) de la microcuenca del río Bermúdez, provincia de Heredia, Costa Rica. Esta caracterización se basa en una clasificación según criterios de uso de estos espacios verdes, donde se describen atributos paisajísticos como cantidad, tamaño promedio, área total y condición de cobertura de la tierra; y atributos biológicos como riqueza de especies, géneros y familias, porcentajes de especies exóticas y nativas por categoría de AVU. Se utilizaron datos geoespaciales en el caso del componente paisajístico, provenientes de los municipios, así como fotointerpretación y generación de cartografía propia, y, para el componente biológico, muestreos de campo y consultas a expertos, fuentes secundarias mediante una revisión exhaustiva de literatura científica y de las bases de datos en línea. Los resultados muestran que existe 8.95% (664.68 ha) del área total de la microcuenca dedicada a las AVU de conservación de la biodiversidad, de protección del recurso hídrico y de recreación, mientras que la categoría AVU privadas dedicadas a cultivos y pasturas casi cuadriplica las primeras (31.33%; 2 325.81 ha). Se identificó 1 029 especies de árboles, arbustos, hierbas, trepadora, etc., siendo los jardines y calles los que aportan más especies. La fauna de vertebrados está dominada por las aves, seguida por reptiles, anfibios y por último los mamíferos. En conclusión, las AVU del área de estudio muestran diferencias paisajísticas y biológicas importantes en cuanto a cantidad, tamaño, distribución espacial, riqueza florística y faunística, y que en su conjunto forman una trama verde que aporta servicios ecosistémicos a la ciudad.

Palabras clave: Áreas verdes urbanas, riqueza florística, fauna urbana, río Bermúdez, paisaje.

The conformation of the current landscape of the Greater Metropolitan Area (GMA) is the product of anthropic pressure associated with the historical exploitation of natural resources by agricultural activities and urban and industrial development. From its material dimension, the landscape of the GMA is made up of urban nuclei interconnected through the road network, the water network, and the green fabric. The green fabric is made up of a network of public and private green areas (GA), continuous and discontinuous, located in urban and peri-urban areas, which constitute strategic elements for improving the quality of life of its inhabitants, since these areas provide multiple ecosystem services.

In addition to covering a varied range of complexity and morphology, urban green areas (UGA) are important elements, because they contribute to the maintenance and improvement of urban biodiversity, benefit human health and well-being, and bring inhabitants closer to nature (DeKleyn, Mumaw & Corney, 2019; Goddard, Dougill & Benton, 2010; Loram, Warren, Thompson & Gaston, 2011), in addition to important social functions, by providing spaces for leisure, recreation and social interaction, including economic production. These landscape elements contain values that provide territorial identity, in this sense a first step is to know their characteristics and attributes, among them those concerned with their landscape and biology.

There are multiple definitions and classifications of urban green areas (UGA), most are limited to urban public spaces (parks, sports facilities, etc.); however, from the biological perspective it is important for the green fabric network to encompass various categories, including private spaces, such as gardens or those areas dedicated to coffee plantations, pastures, wooded pastures, among others. The foregoing to carry out an appropriate management of the ecological connectivity of UGAs, especially in the case of interurban biological corridors.

This article proposes a classification of UGAs and presents a landscape and biological characterization according to category. UGA classification was based on use criteria such as conservation (biodiversity, water resource protection areas, etc.), recreational use (recreational centers, urban green areas, sports facilities, etc.) and agricultural-forestry use. Landscape attributes such as quantity, average size, total area, condition of land cover and non-conforming uses in some cases are analyzed. Regarding biological aspects, a description of the floristic richness is presented at the level of species, genera, and families, as well as the percentages of exotic and native species by UGA category. At the fauna level, the characterization was general, and emphasis was given to birds, since it is an indicator group that is easy to monitor, conspicuous and with a worldwide distribution, in addition to this being related to their degree of tolerance to urbanized environments.

Study area

For the study of UGAs within GMA, the Bermúdez River micro-basin was selected. This micro-basin comprises an approximate area of 74.24 km² (7.424 ha) that includes totally or partially the following districts of various cantons: Concepción, San Rafael, San Josecito and Santiago (all belonging to the Canton of San Rafael); Heredia, Mercedes, San Francisco and Ulloa (all belonging to the Canton of Heredia); San Pablo and Rincón de Sabanilla (all belonging to the Canton of San Pablo); the districts Santo Domingo and San Vicente (both belonging to the Canton of Santo Domingo); the districts Santa Lucía and Barva (both belonging to the of Canton Barva); the district of San Francisco de San Isidro (Canton of San Isidro); and the districts of San Antonio, La Asunción and La Ribera (all belonging to the Canton Belén); and the district of San Rafael of the Canton of Alajuela. The population within the micro-basin for 2011, according to the last population census of the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses, was 163.678 inhabitants, corresponding to a population density of 2.204 inhabitants/km2 (Cambronero-Chacón, Marín-Marín, & Reyes-Rojas, 2019).

Classification of urban green areas

The present article proposes six classification criteria for green areas for basins with a predominance of urban use, in addition, urban green area (UGA) is defined as any surface whose land cover contains some type of vegetation, being it forest, scrubland, forest primary succession, gardens, trees, pastures, crops, forest plantations; whether public or private, for multiple uses including conservation, recreation or agricultural and forestry production. These criteria are detailed in Table 1:

Table 1. Categorization, definition, and methodologies of the urban green areas present in the micro-basin of the Bermúdez River, Heredia, Costa Rica

|

NAME OF CATEGORY |

NAME OF SUBCATEGORY |

DEFINITION |

METHODOLOGY |

|

Green areas destined for biodiversity conservation purposes |

Protected Wildlife Area (PWLA) |

“Geographic area defined, officially declared and designated with a management category by virtue of its natural, cultural and/or socioeconomic importance, to meet certain conservation and management objectives.” Biodiversity Law (in Spanish Ley de Biodiversidad) (Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica, 1998). |

The identification and mapping PWLAs in the study area was based on the information available at SINAC. |

|

Green areas destined for the protection of water resources |

River and creek protection areas (RCPA) |

Protection area spanning 10 horizontal/linear meters on both banks of the body of water in areas with slopes of less than 40% in urban areas and 15 horizontal meters in rural areas. Because Law 7575 does not include the peri-urban category, the distance applied in the present study for protection purposes was 15 linear meters. In areas with slopes greater than 40% the required distance for protection is 50 horizontal meters. Water Law (Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica, 1942) and Forestry Law (Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica, 1996). |

Mapping of the vegetation cover was carried out from the photointerpretation of images from 2017 available in the Base Map of ARC GIS 10.5, which contains Digital Globe images of 0.31-0.50 mm resolution. |

|

Water well Protection Areas (WWPA) |

Water extraction sites for domestic use that contain a protection area of 40 meters radius (around the well) that must be protected with vegetation cover (Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica, 1942) and the Forestry Law (Legislative Assembly of the Republic of Costa Rica, 1996). |

Data of water wells and springs was obtained from SENARA, and the protection area was delimited digitally and according to the radius, using the same methodology as for RCPA. |

|

|

Springs protection areas (SPA) |

Water extraction sites for domestic use that contain a protection area of 100 meters in radius (around the source) that must be protected with vegetation (Legislative Assembly of the Republic of Costa Rica, 1942) and Forestry Law (Legislative Assembly of the Republic of Costa Rica, 1996). |

||

|

Green areas for multiple public use (UGA-Pu) |

Urban parks (PU) Sports facilities (SF) Recreational parks (RP) Multi-use residential green areas (RGA) |

Spaces managed by a public entity such as municipalities, development associations or cantonal sports committees, with some type of vegetation, located outdoors and accessible to the public, free of charge or at some cost (Ministry of Health of Costa Rica, 2020). |

It was carried out by integrating two geospatial databases: vegetation cover data obtained from the photointerpretation and data provided by the Departments of Environmental Management of municipalities, in some cases data was corroborated using online aerial/satellite images. |

|

Street green areas |

Tree-lined streets (TLS) |

Alignments of trees or shrubs in public streets, whose purpose is to beautify the city, provide shade, protect from the wind or the sun, among others (Sánchez, 2003), which are administered by the municipalities or the national governing body (MOPT) in the case of national roads. |

Landscape analysis was not carried out because high resolution aerial images or photos are not available. |

|

Private Gardens (Gar) |

Home gardens (gardens or patios of houses) Gardens belonging to condominiums Gardens owned or managed by private organizations or entities |

Private spaces partially or totally covered by vegetation of different types (González-Ball, Bermúdez-Rojas & Romero-Vargas, 2017). |

Landscape analysis was not carried out due to the lack of high-resolution aerial images or photographs. |

|

Agricultural, livestock and forestry areas (AAg) |

No subcategories were defined |

Private spaces destined to pastures (alone or combined), permanent/annual crops and forest plantations. According to the classification of coverage and land use of INTA-MAG/INTA/FITTACORI/SUNII, 2015 and CENIGA 2018. |

Mapping of the vegetation cover was carried out from the photointerpretation of images from 2017 available in the Base Map of ARC GIS 10.5, which contains Digital Globe images of 0.31-0.50 mm resolution. |

Source: Own elaboration.

Characterization of flora and fauna

To determine the richness of flora and fauna species present in the UGAs of the Bermúdez River micro-basin, primary sources of information were used such as field samplings and consultation with experts, as well as secondary sources through an exhaustive review of scientific literature (articles, theses, and reports) and online databases. In the case of flora, databases from municipalities were additionally employed, while for birds’ information it was used the Ebird application (https://ebird.org/region/CR) was consulted. This combination of methodologies allowed to triangulate the information and corroborate the presence of the most frequent species in the micro-basin, however, as expected, there is a risk of underestimating the presence of some species that are either difficult to observe or that present reduced populations.

The collected information was systematized in an Excel spreadsheet, based on the richness of families, genera and species identified for the floristic component and for some selected fauna groups (mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians). In the case of flora, the percentages of exotic and native species were also determined by type of UGA, as well as the main forms of life.

To establish the degree of tolerance of fauna species to urbanized environments and the ecological function of the UGAs present in the micro-basin, the group of birds was selected; this considering that birds are frequently used for environmental monitoring, as they are ecologically and taxonomically very diversified, of worldwide distribution, conspicuous and with a marked sensitivity to environmental changes (Perepelizin & Faggi, 2009).

To analyze the degree of tolerance of bird species to urbanized environments, three criteria were established: a) degree of dependence on available human resources, b) population density of the species and c) frequency of occurrence. Based on the previous criteria and using the classification proposed by Blair (1996, modified by McKinney, 2002) the species were classified into three categories: 1) urban exploiters (ExU), 2) urban adapters (AdU) and 3) urban avoiders (AvU). For a species to be classified in any of these three categories, it had to meet at least two of the three established criteria. The characteristic of each category is detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Definition of the criteria for classifying bird species according to their degree of tolerance to urban environments

|

Criteria |

Exploiters of Urban Environments (ExU) |

Adapters to Urban Environments (AdU) |

Avoiders of Urban Environments (AvU) |

|

Dependency on human resources |

HIGH They use different human resources for shelter, food, and reproduction |

MEDIUM They use the green components of urban areas (sports facilities, parks, gardens, tree-lined streets, boulevards) |

LOW Occasionally make visits to urban areas, mainly in search of food |

|

Population density in urban environments |

HIGH Its population density is high in the urban environment compared to natural environments |

MEDIUM The population density is higher in natural environments, however, there are established populations in urban environments |

LOW Populations inhabit natural environments, but some individuals occasionally visit urban environments |

|

Observation frequency in urban environments |

VERY FREQUENT It can be observed several times a week in urban environments |

FREQUENT It can be observed at least once a week in urban environments |

INFREQUENT It is observed occasionally (once or twice a month) in urban environments |

Source: Own elaboration.

Landscape characterization of urban green areas

As a result of the historical processes of the society-nature relationship, geographic spaces acquire their own forms, patterns, and identities, with which it is possible to identify, for example, spaces with rural, urban, and peri-urban characteristics. Peri-urban spaces have a transitional character between the so-called urban and rural, it is that space wherein urban and agricultural activities, and even conservation areas, coexist; its economic, social, environmental, and ecological value has been pointed out by several authors (Barsky, 2005; García-González, Carreño-Meléndez & Mejía-Modesto, 2017; Hernández-Puig, 2016; Martínez-Cruz & Sainz-Santamaría, 2017; Vasco, Bernal & Soto, 2005).

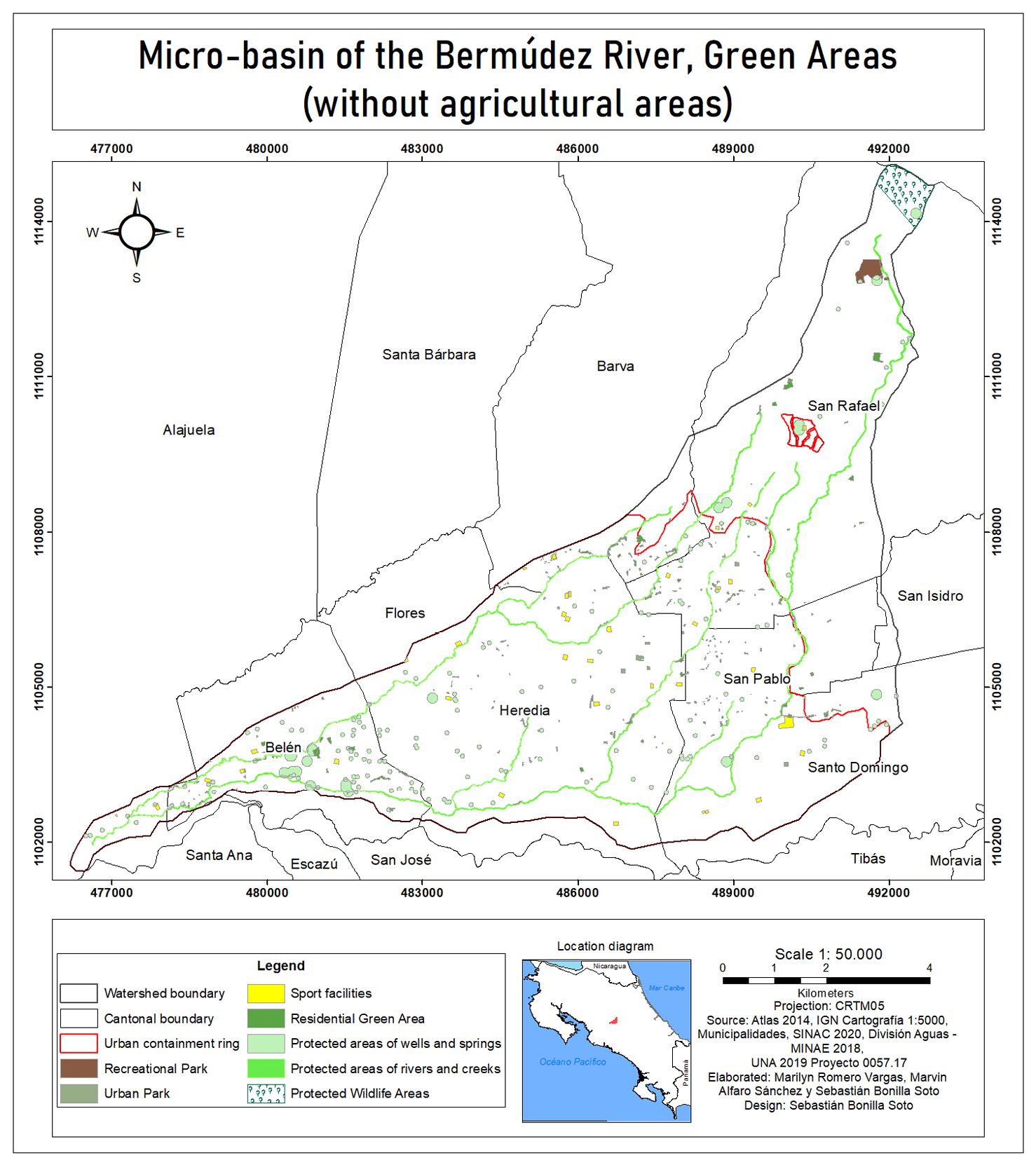

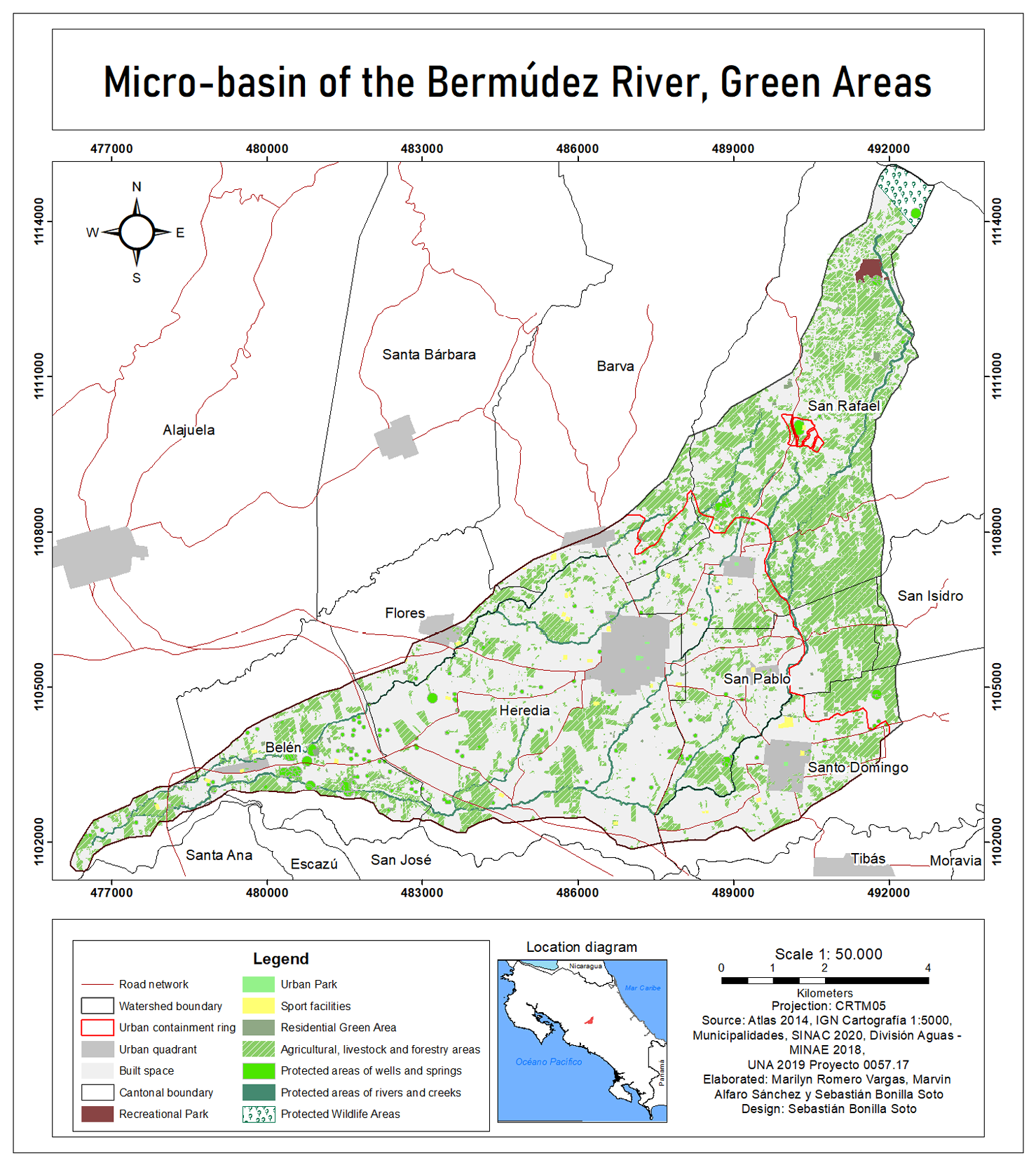

In the case of the study area, the delimitation between urban and peri-urban was based on the limit of the Urban Containment Ring (UCR) (Map 1) defined by the GMA Plan 2013-2030 (Consejo Nacional de Planificación Urbana, 2013). In this plan, in addition to establishing the urban growth limit of the cities and its associated urbanistic regulations, it is possible to identify macrozones of land use regulation. In the study area, two macrozones were identified outside the UCR: a) a Protection and Preservation macrozone (PPM) and b) an Agricultural and Livestock Production macrozone (ALPM), which also includes the subzone of urban recovery and the subzone of peripheral centralities (urban quadrants). For the purposes of the present study, the peri-urban area of the micro-basin was defined as that area outside the UCR possessing PPM and ALPM characteristics, the foregoing because the PPM area is very small compared ALPM whose characteristics are more typical of a peri-urban space. However, for future studies on a more detailed scale it would be important to specify the peri-urban area, separating it from the conservation area. c) The third macrozone identified is located within the UCR and is denominated Urban macrozone (UM) and includes a restricted urban growth subzone; in the present study, UM was classified as an urban area.

The urban green area categories: PWLA, RCPA, WWPA, SPA and UGA-Pu covered 8.95% (664.68 ha) of the total area of the micro-basin (Table 3 and Map 1), while the AAg category adds up 31.33% (2 325.81 ha) (Table 3 and Map 2), thus the Bermúdez River micro-basin is comprised of approximately 40.28% green areas, distributed throughout its territory.

According to Cambronero-Chacón et al. (2019) the built area within the micro-basin accounts to almost 50% and other half corresponds to multiple-use green spaces, therefore, the management of green areas is important to preserve the natural capital and ecosystem services that GAs, both public and private (such as coffee and wooded pastures) encompass and provide. These areas are exposed to multiple anthropic strains, especially coffee plantations and pastures that compete with urban land use and RCPAs (rivers and creeks protection areas) that find themselves constantly exposed to urbanistic pressure.

Table 3. Landscape aspects of public UGAs in the micro-basin of the Bermúdez River, Heredia, Costa Rica

|

CA |

Zoning |

# |

A (ha) |

P (%) |

T (m²) |

ST |

CT (ha) |

|

|

ha |

% |

|||||||

|

PWLA |

1 2 |

0 1 |

69.81 |

0.94 |

69,810 |

0.24 |

0.34 |

Forests 69.57 Pastures 0.24 |

|

RCPA |

1 y 2 |

7 |

170.63 |

2.29 |

Max 59.41 (RB) Min 4.52 (QGer) Average 24.38 SD 17.12 Width according to Forestry Law 7575 Length depends on the length of each water body |

70.47 |

41.29 |

Forest 85.97 Scrubland 2.15 Forest primary succession 12.08 Other uses (coffee, pastures, urban) 70.47 |

|

WWPA |

1 |

140 |

71.5 |

0.96 |

40-meter radius. |

64.91 |

90.52 |

Forest, Scrubland, and Forest primary succession: 6.59 Coffee, pastures, and, urban 64.91 |

|

2 |

14 |

|||||||

|

SPA |

1 |

15 |

72.25 |

0.97 |

100-meter radius. |

41.87 |

71.51 |

Forests, Scrubland and, Primary Forest succession 30.38 Coffee, pastures, and urban 41.87 |

|

2 |

8 |

|||||||

|

UP |

1 |

8 |

4.03 |

0.05 |

Max 7,832.63 Min 408.95 Average 3,671.42 SD 2,367.49 |

(-) |

Infrastructure, arboreal vegetation, and shrubland |

|

|

2 |

0 |

|||||||

|

RP |

1 |

0 |

2.08 |

0.03 |

There is only one site of this kind in the entire micro-basin |

(-) |

Infrastructure, Arboreal, shrubby, and herbaceous vegetation |

|

|

2 |

1 |

|||||||

|

SF |

1 |

30 |

26.68 |

0.35 |

Max 43,865 (Santo Domingo Sports Facilities “Polideportivo”) Min 791.47 Average 7,020.12 |

(-) |

Herbaceous vegetation in, and trees in the periphery of the facilities. |

|

|

2 |

2 |

|||||||

|

RGA |

1 and 2 |

389 |

41.78 |

0.56 |

Max 20,761 Min 15.14 Average 1,073.95 SD 2,251.86 |

(-) |

Infrastructure, Arboreal, shrubby, and herbaceous vegetation |

|

|

AAg |

1 and 2 |

281 |

2,290.83 |

30.85 |

Max 11,795,890.03 Min 0.002 Average 1,761,489.30 SD 1,009,815.13 to 40,862.70 depending on the type of crop. |

(-) |

Coffee 1,027.82 Pasture 1 206.97 Forest plantations 10.29 Other crops 45.75 |

|

Symbology: CA: Category. NP National Park (Braulio Carrillo). RCPA: Rivers and Creeks Protection Area: 7 main tributaries: BR Bermúdez, TR Turales, QS Seca, BR Burío, PR Pirro, QG Guaria, QGer Gertrudis. WWPA Water Well Protection Areas, SPA Springs Protection Areas. UP Urban Parks, RP Recreational Parks, SF Sports facilities. RGA Residential Green Areas for Multiple Uses, AAg Agricultural, Livestock and Forestry Areas. Zoning: 1. Peri-urban land use, 2. Urban land use. Delimited based on the GMA Urban Containment Ring. # Number of polygons or sites. A (ha) Total area of the category. P (%) percentage of total area. T (m2) average size of the polygons or sites. ST (ha, %) Area in overuse or land use not in accordance with the Law. CT (ha) coverage and land use. Bermúdez river micro-basin area = 7,424 ha. (-) Does not apply or there is no data. SD STANDARD DEVIATION

Note. Overuse (ST) means a conflict in land use due to the existence of a use not in accordance with the provisions of Forest Law 7575 for protection areas.

Source: Prepared from geospatial data provided by Municipalities, SINAC, SENARA and the 2017 Land Cover Map generated by Project 0057-17 SIA-UNA.

There is a single site categorized as Protected Wildlife Area (PWLA) whose area is 69.81 ha, that is, less than 1% of the micro-basin area. The land cover of this site is mostly forest as it is located within the Braulio Carrillo National Park, in the upper part of the micro-basin, in the peri-urban area, in the districts of Concepción and Los Ángeles of the province of Heredia. (Table 3, Map 1).

The RCPA category constitutes the largest green area with 170.63 ha equivalent to 2.29% of the micro-basin area, of which the Bermúdez River is the largest RCPA with 59.41 ha, followed by Quebrada Seca (29.68 ha) and Turales River (29.25 ha), Burío River with 24 ha, Pirro River with 17.81 ha, Quebrada Guaria with 5.96 ha and Quebrada Gertrudis with 4.52 ha. Of the total hectares of RCPA, 41.29% (70.47 ha) are characterized as in overuse, which means that they do not have land use coverage in accordance with the Forest Law Nº7575, that is, this area is not forested (Table 3, Map 1).

In relation to WWPAs, this category has an area of 71.5 ha, 154 registered water wells, of which 90 percent are in the urban area, which possibly explains the high percentage of overuse (90.52%) or non-compliant use in terms of land cover, which by law must be forest. The 26 registered springs (SPAs) cover an area of 72.25 ha, mostly located in the urban area, and although they present a better situation in terms of protection, 71.51 percent of the protection area does not have a coverage of forest, scrubland, or forest primary succession as established by law (Table 3, Map 1).

Map 1. Micro-basin of the Bermúdez River, Urban Green Areas, categories, and subcategories present in the landscape (without agricultural areas): PWLA, RCPA, WWPA, SPA, UGA-Pu.

Source: Own elaboration.

Map 2. Micro-basin of the Bermúdez River, Urban Green Areas, categories, and subcategories present in the landscape: PWLA, RCPA, WWPA, SPA, UGA-Pu including the areas destined to agriculture, livestock, and forestry (AAg).

Source: Own elaboration.

Regarding the category of public urban green areas UGA-Pu, the micro-basin has the 5 established subcategories, however, its total area is only 1% (74.57 ha) of the micro-basin (Table 3, Map 1). All of them present some type of arboreal and bushy vegetation. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cities should have at least 9 m2 of green space per inhabitant and 50 m2 ideally (Yukhnovskyi & Zibtseva, 2019). However, Latin American cities have an average of 3.5 m2 of green area per inhabitant (Sorensen, Barzetti, Keipi & Williams, 1998). In the case of the study area, there is approximately 4.55 m2 of green area per inhabitant, thus it does not reach the minimum established by WHO.

Within UGAs-Pu, residential green areas (RGA) exhibit the largest area with 41.78 ha, followed by Sports fields (in Spanish plazas de fútbol) (SF) with 26.68 ha, urban parks (UP) with 4.03 ha and recreational parks (RP) with 2.08 ha. RGAs are the largest category with 389 sites, all with multiple uses: from children's games, calisthenics, recreation, and so on. The average size is 1,073.95 m², with very varied sizes ranging from 15.14 m² to 20,761 m². In the case of the UPs, the 8 existing sites are in the urban area, with an average size of 3,671.42 m². Sports fields have very similar sizes in most places because they are established primarily for practicing soccer, however, the existence of the Santo Domingo Sports Center (in Spanish Polideportivo de Santo Domingo) (43,865 m²), which has several adjoining sport fields, increases the average size of sports fields high (7,020.12 m²) compared to the minimum (791.47 m²) (Table 3, Map 1).

In the case of recreational parks (RP), there is a single site with an area of 2.08 ha, called Monte de la Cruz Recreational Park, located in a peri-urban area, in the district of Los Angeles de San Rafael de Heredia, which is currently managed by the Municipality of San Rafael de Heredia (Table 3, Map 1).

Regarding the category of agricultural green areas AAg (agricultural, livestock and forestry areas), 30.85% of the micro-basin (2,290.83 ha) presents some type of use associated with pastures, crops, and forest plantations. In the crops, coffee plantations stand out at 13.84% of total coverage (1,027.82 ha), while other crops represent less than 1% (45.75 ha; 0.61%). Pastures (alone or wooded) represent 16.25% of the micro-basin (1,206.97 ha). Forest plantations are minimal, representing little more than 1% (10.29 ha: 1.38%) (Table 3, Map 2). It is important to note that, according to the data reported by Cambronero-Chacón et al. (2019), fragments of forest, scrubland, and forest primary succession occur only within PWLAs and in RCPA, WWPA and SPA.

Composition and richness of flora

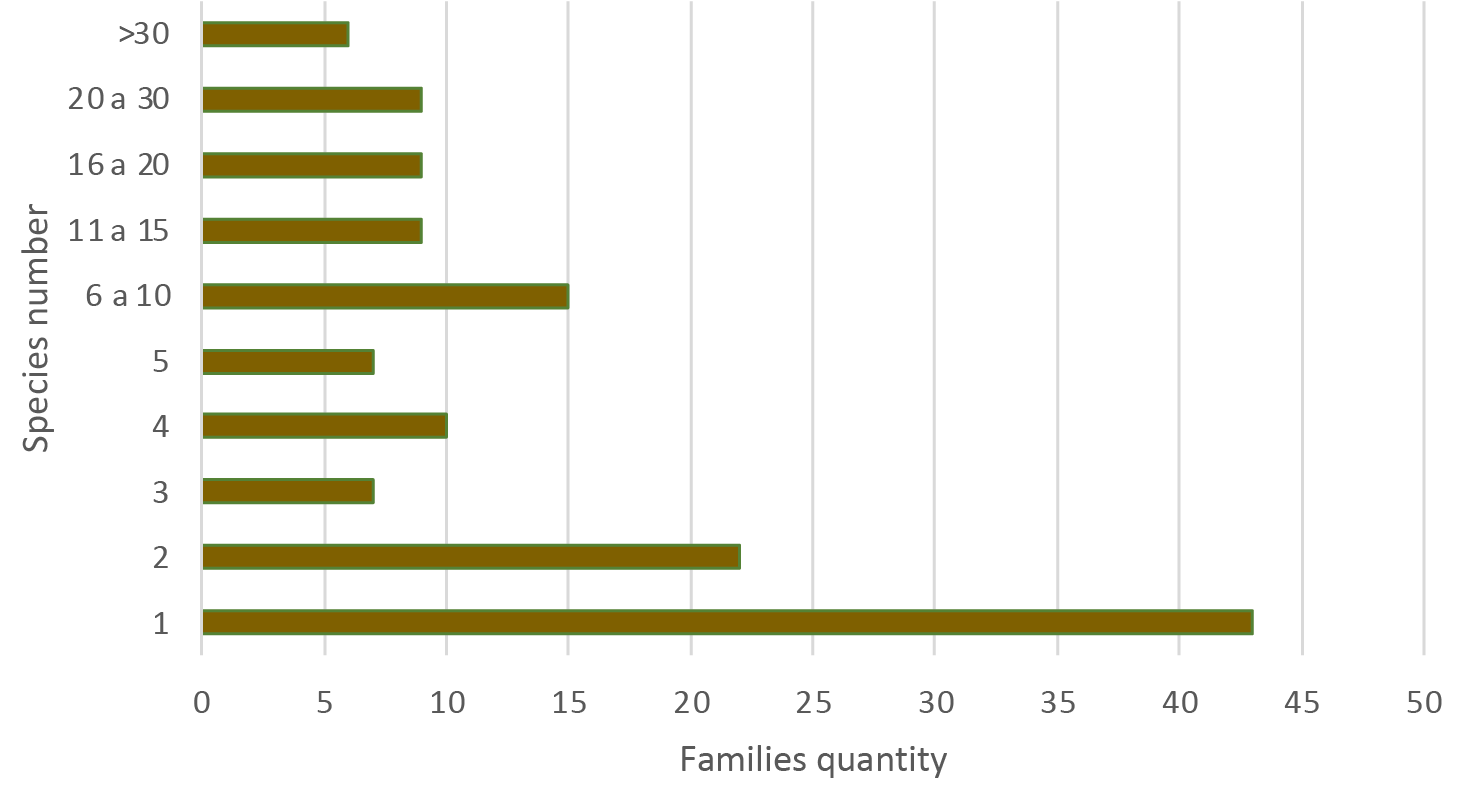

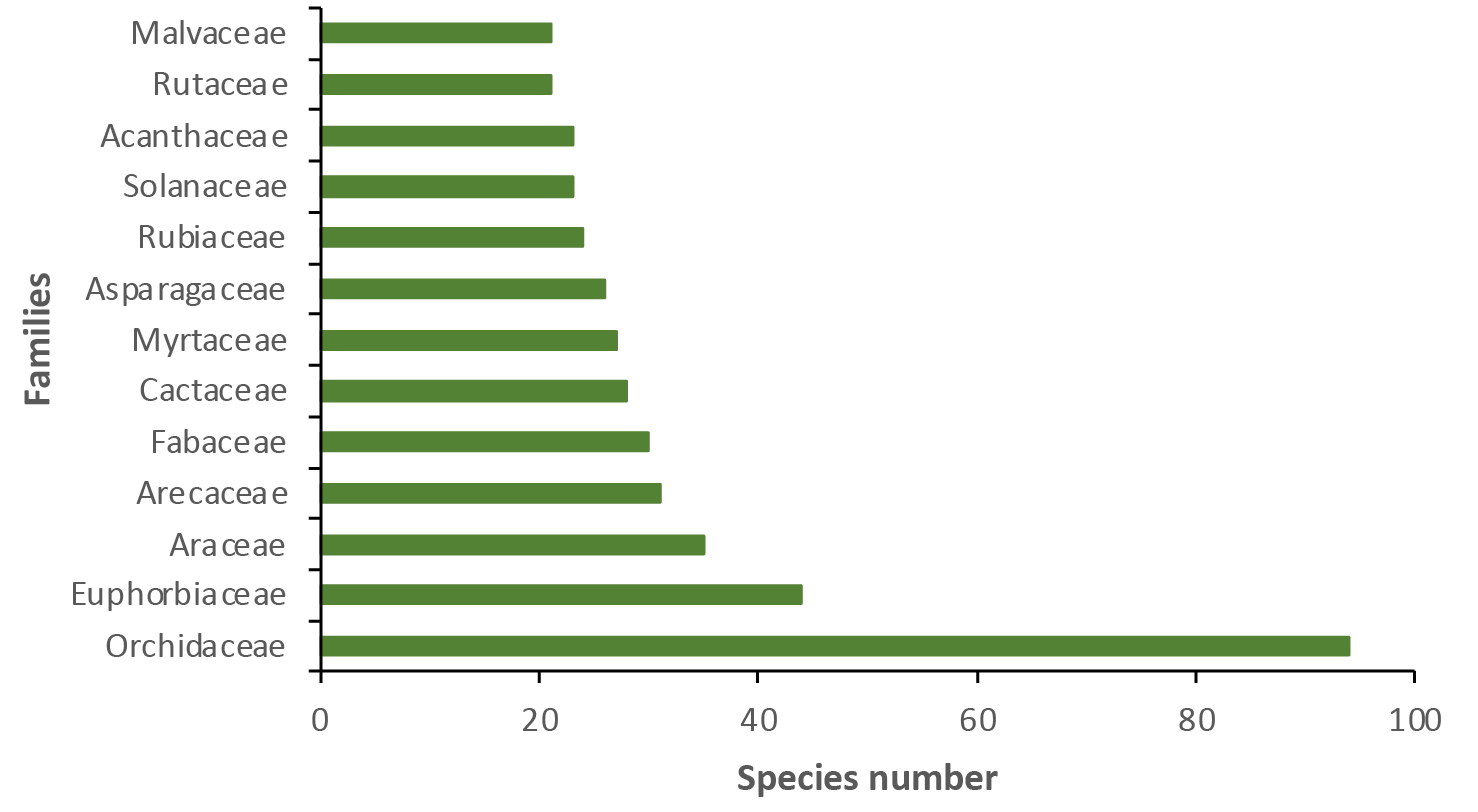

The flora richness of all the UGAs of the Bermúdez River micro-basin corresponded to 1,029 species and 569 genera, distributed in 136 families of which 667 species belong to dicotyledons, 330 to monocots, 15 to gymnosperms and 17 to Pterydophyta. Most of the families registered few species, between one and ten, which represents 76.5% of the total (Figure 1). Of the most abundant families with more than 20 species, 14 were counted (Figure 2), with the exceptional case of Orchidaceae with 94 species.

Figure 1. Number of families distributed by number of species in the Bermúdez River micro-basin, Heredia, Costa Rica

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 2. Families with the highest species richness in the UGAs of the Bermúdez River micro-basin, Heredia, Costa Rica.

Source: Own elaboration.

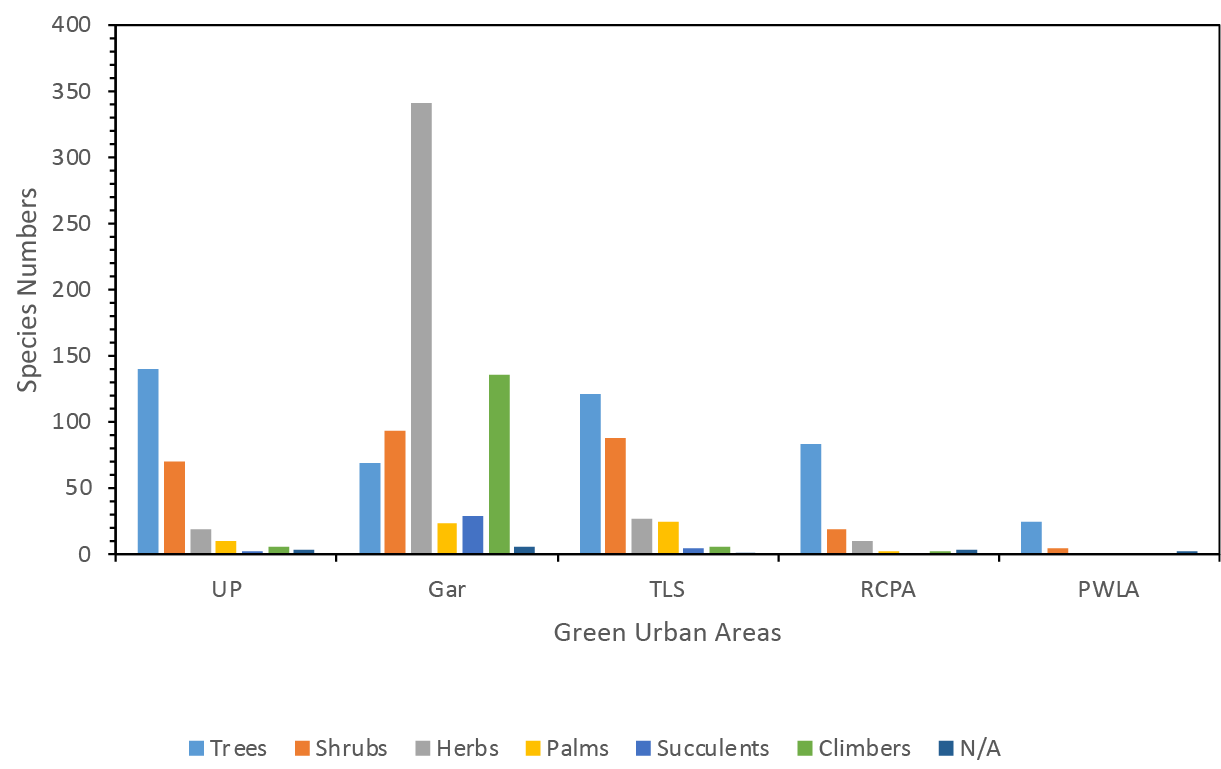

The UGA with the highest species richness corresponded to the category of Private Gardens (Gar), while Protected Wildlife Areas (PWLA) (Table 4) registered the lowest abundance. In the latter case, very little secondary information was obtained, evidencing the lack of studies in these areas.

Exotic flora species corresponded to 55% (565), native flora 43% (442) and 2% (22) were indeterminate. Private gardens and tree-lined streets presented a greater quantity of exotic species, mainly related to cultivated species. In tropical urban ecosystems, exotic plants are widely used in landscaping (Oliveira et al., 2020), thus their dominance in private gardens and streets. Further, incorporation of native species is possibly limited by the scant offer of commercial nurseries mainly due to the prevailing large international market for exotic species, coupled with the existence of highly accessible technological packages related to these species (Murillo, 2005).

Table 4. Richness, families, and percentage of exotic and native species found in the UGAs of the Bermúdez River micro-basin: Urban Parks (UP); Private Gardens (Gar); Tree-lined streets (TLS); Rivers and creeks Protection Area (RCPA); Protected Wildlife Area (PWLA)

|

Variable |

URBAN GREEN AREAS |

||||

|

UP |

Gar |

TLS |

RCPA |

PWLA |

|

|

Absolute richness |

248 |

695 |

269 |

118 |

30 |

|

Richness % |

18% |

51% |

20% |

9% |

2% |

|

Richness of families |

64 |

102 |

68 |

41 |

22 |

|

Exotic species (%) |

110 (44.4%) |

440 (63.3%) |

154 (57.2%) |

27 (22.9%) |

7 (23.3%) |

|

Native species (%) |

130 (52.4%) |

251 (36.1%) |

110 (40.9%) |

86 (72.9%) |

17 (56.6%) |

|

Indeterminate |

8 (3.2%) |

4 (0.6%) |

5 (1.9%) |

5 (4.2%) |

6 (20%) |

Source: Own elaboration based on field samplings and consulted information sources.

When analyzing the life forms (Figure 3) of the flora species present in the UGA of the micro-basin, it is observed that the trees are present in all the types of UGAs, however, gardens present a dominance of herbs and an important number of climbers that are not registered in the other areas.

Figure 3. Life forms of the flora species present in each UGA of the Bermúdez River micro-basin: Urban Parks (UP); Private Gardens (Gar); Tree-lined streets (TLS); Rivers and creeks Protection Areas (RCPA); Protected Wildlife Areas (PWLA).

Source: Own elaboration.

Composition and fauna richness

Based on the compilation of information from the consulted primary and secondary sources, it was possible to determine that there are more than 300 species of vertebrate animals reported in the micro-basin of the Bermúdez River (Table 5). Birds was the best prominent group representing around 25% of the diversity registered for the country; followed by reptiles with 19%, amphibians with 11%; the lowest fauna richness corresponded to mammals with only 8.5% of the total.

Table 5. Diversity of some vertebrate faunal groups reported for the Bermúdez River micro-basin, Heredia, Costa Rica.

|

Faunal group |

Families |

Genera |

Species |

|

Birds |

51 |

165 |

232 |

|

Mammals |

10 |

16 |

20 |

|

Amphibians |

9 |

13 |

22 |

|

Reptiles |

19 |

33 |

45 |

Source: Own elaboration based on field samplings and consulted information sources.

Relationship of avifauna and urbanized environments

Urban exploiter species are generally considered synanthropic, meaning that they adapt with some ease and speed to environmental conditions created or modified because of human activity. These species also tend to be generalists in their diet and habitat use; likewise, they present high ecological plasticity, which is why they are more efficient exploiting the resources available in urban areas, even over native species (Blair, 1996).

In the most urbanized part of the micro-basin, some typical species the urban exploiters group were reported, for example, the great-tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus), common pigeon (Columba livia), house sparrow (Passer domesticus), and the rufous-collared sparrow (Zonotrichia capensis). These species have been associated in several countries with urban centers, which are characterized by high densities of people and houses, a higher concentration of buildings and other infrastructure works, as well as high noise levels (Rodrigues, Borges-Martins & Zilio, 2018).

In the case of the common pigeon, house sparrow, and the rufous-collared sparrow, even though they have a primary granivorous diet, they have adapted to take advantage of other resources available from human-derived wastes (refuse) to complement their diet, and they can also use certain infrastructures (cornices, metal trusses and edges or projections of buildings) to build their nests (Ferman, Peter & Montalti, 2010). The great-tailed grackle, for its part, is considered an “opportunistic” bird (Gurrola-Hidalgo, Sánchez-Hernández & Romero-Almaraz, 2009) that uses both exotic and native trees to build its nests and takes advantage of the availability of fruit and seed feeders for feeding (Shochat, Lerman & Fernandez-Juricic, 2010). This contrasts with a primary carnivorous diet when in its natural habitat (Styles & Skutch, 2007).

On the other hand, the presence of species identified as adapters to urban environments may be an indication of environments with intermediate levels of urbanization associated with a greater availability of plant cover (Villegas & Garitano-Zavala, 2008). In this case, the vegetation present in urban parks and other green areas of the micro-basin can become an important source of food resources, water and shelter for many animals including birds (Pineda-López, Malagamba-Rubio, Arce & Ojeda, 2013).

The greater availability of resources from these green areas can be related to the presence of a greater diversity of trophic guilds. In the UGAs of the micro-basin, it is common to observe frugivorous species such as Thraupis episcopus (blue-gray tanager), T. palmarum (palm tanager); granivores such as Columbina passerine (common ground dove), Zenaida asiatica (white-winged dove); nectarivores such as Amazilia tzacatl (rufous-tailed hummingbird) and A. rutila (cinnamon hummingbird); insectivores such as Melanerpes hoffmannii (Hoffmann's woodpecker) and Tyrannus melancholicus (tropical kingbird) and other more generalists such as Turdus grayi (clay-colored thrush, yigüirro in Costa Rican Spanish), Pitangus sulphuratus (great kiskadee) and Momotus lessonii (Lesson's motmot).

In this sense, in Heredian urban parks many native tree species were recorded such as Croton draco (targuá), Cinnamomum triplinerve (aguacatillo), Muntingia calabura (capulín), Ardisia revoluta (tucuico), Ficus davidsoniae (higuerón), Psidium friedrichsthalianum (cas), Malpighia glabra (acerola), Trichilia havanensis (uruca), among others, which are sources of fruits, seeds, arils and nectar for avifauna (Camacho-Varela, 2017).

On the other hand, in private gardens and some public green areas (residential complexes) a variety of fruit trees were also identified such as Annona cherimola (anona), Byrsonima crassifolia (nance), Carica papaya (papaya), Spondias purpurea (jocote), Manguifera indica (mango), Persea americana (avocado), Psidium guajava (guava), as well as ornamental plants such as Heliconia spp (platanillas), Hamelia patens (scarlet bush or Texas firebush), Acnistus arborescens (güitite), Citharexylum donnell-smithii (dama), which are also available resources for the fauna in general (González-Ball et al., 2017).

Urban green areas also play a very important role as temporary habitats for the maintenance of migratory birds (Fallas-Solano, 2018). In the urban parks of the micro-basin, the presence of at least 20 migratory species has been recorded, such as Archilochus colubris (ruby-throated hummingbird), Empidonax flaviventris (yellow-bellied flycatcher), Vireo philadelphicus (Philadelphia vireo), Protonotaria citrea (prothonotary warbler), Icterus galbula (Baltimore oriole), Piranga rubra (summer tanager), Setophaga petechia (yellow warbler) and S. ruticilla (American redstart) (Camacho-Varela, 2017).

Grouped into the category of avoiders of urban environments were those species less tolerant to human intervention, and that, therefore, are more demanding of plant covers possessing a higher degree of conservation (Styles & Skutch, 2007). The presence of this type of species near urbanized sectors may be related to the use of vegetation cover or forest remnants located on the banks of the Bermúdez River and its tributaries. In the upper part of the micro-basin, in the peri-urban area, these birds can take advantage of the combination of cultivation areas and the forested areas that adjoin the Braulio Carrillo National Park.

The above situation is evident when considering that more than 20 species of birds associated with ecosystems or aquatic environments have been identified. The group with the highest representation, as expected due to its diversity and adaptability, is that of herons. Common species reported were the little blue heron (Egretta caerulea), snowy egret (E. thula), cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis), green heron (Butorides virescens), great egret (Ardea alba) and the great blue heron (A. herodias). These birds have a broad diet that includes fish, amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals. To a lesser degree, species such as the American white ibis (Eudocimus albus), the russet-naped wood rail (Aramides albiventris) and the northern jacana (Jacana spinosa) were observed, foraging among the aquatic vegetation of rivers, ponds, and lagoons in search of small fish, insects, arachnids, and crustaceans among others (Styles & Skutch, 2007).

AAgs are important for their ecological contribution as they provide habitat and food for both local and migratory birds (Leyequien & Toledo, 2009). In the urban area of the micro-basin there are some remaining fragments of coffee cultivation activity (coffee plantations), mixed within a growing urban matrix. At the Latin American level, in coffee plantations, especially those managed under the shade-grown technique, richness of bird species similar or even greater than those observed in forest ecosystems have been reported (Leyequien & Toledo, 2009), which shows the importance of this type of coverage for the conservation of biodiversity.

From the landscape point of view, the Bermúdez River micro-basin has approximately 40.28% of green areas, of which only 8.95% (664.68 ha) correspond to the categories destined to the conservation of biodiversity (PWLA), conservation of water resource (RCPA, WWPA, SPA) and recreation spaces (UGA-Pu), the remaining 31.33% (2,325.81 ha) corresponds to agricultural areas (AAg), mainly pastures and coffee plantations.

The peri-urban area has the only protected wildlife area, which is part of the Braulio Carrillo National Park, as well as the only recreational area in the micro-basin: Monte de la Cruz Recreational Park. The urban area contains most of the green areas for public use (UGA-Pu), however, the minimum area established by WHO is not met.

The Bermúdez River micro-basin presents a floristic diversity of 1,029 species of trees, shrubs, herbs, climbing plants, etc., where gardens and streets provide the most species. This influences the presence of more exotic species, following the patterns of many cities in the world.

The vertebrate fauna in this micro-basin is dominated by birds, followed by reptiles, amphibians and, lastly, mammals. When analyzing the group of birds, it is observed that the species classified as exploiters of urban environments are characterized by inhabiting places with high densities of people and houses, a greater concentration of buildings, as well as high noise levels. Species adapted to urban spaces are common in green areas within the city and, finally, avoiders of urban environments are typical of the peri-urban zone of the micro-basin, close to forest nuclei and protected wildlife areas.

Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica. (1998). Ley de Biodiversidad N°7788. Versión de la norma: 21/11/2008. http://www.pgrweb.go.cr.

Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica. (1942). Ley de aguas Nº276. Versión de la norma: 25/06/2012. http://www.pgrweb.go.cr.

Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica. (1996). Ley Forestal Nº7575. Versión de la norma: 5/06/2012. http://www.pgrweb.go.cr.

Barsky, A. (2005). El periurbano productivo, un espacio en constante transformación. Introducción al estado del debate, con referencias al caso de Buenos Aires. Scripta Nova, 9(194).

Blair, R. B. (1996). Land use and avian species diversity along an urban gradient. Ecological Applications, 6(2), 506–519. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2269387

Camacho-Varela, P. (2017). Inventario, identificación y rotulación de especies forestales en los parques públicos de Heredia. Informe técnico, Municipalidad de Heredia, Costa Rica. https://www.heredia.go.cr/es/bienestar-social/noticias/gestion-ambiental/

Cambronero-Chacón, E. D., Marín-Marín, M. & Reyes-Rojas, G. (2019). Análisis del capital natural y los servicios ecosistémicos para la definición de un corredor biológico interurbano en la microcuenca del río Bermúdez. (Tesis de Licenciatura). Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica. https://repositorio.una.ac.cr/handle/11056/18151

CENIGA. (2018). Sistema de clasificación del uso y la cobertura de la tierra para Costa Rica v1.2. Centro Nacional de Información Geoambiental, SistemaNacional de Monitoreo de Cobertura y Uso de la Tierra y Ecosistemas (SIMOCUTE), Costa Rica. https://simocute.go.cr/documentos/

Consejo Nacional de Planificación Urbana. (2013). Plan GAM 2013-2030. Informe técnico. http://www.mivah.go.cr

DeKleyn, L., Mumaw, L. & Corney, H. (2019). From green spaces to vital places: connection and expression in urban greening. Australian Geographer, 51(2), 205-219. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2019.1686195

Fallas-Solano A. (2018). Riqueza de especies y abundancia de aves residentes y migratorias en parques urbanos de San José, Costa Rica. UNED Research Journal, 10(1): 21-32. doi: https://doi.org/10.22458/urj.v10i1.2037

Ferman L. M., Peter, H. U. & Montalti, D. (2010). A study of feral pigeon Columba livia var in urban and suburban areas in the city of Jena Germany. Arxius de Miscellania Zoologica, (8), 1-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.32800/amz.2010.08.0001

García-González, M. L., Carreño-Meléndez, F. & Mejía-Modesto, A. (2017). Evolución de los conjuntos urbanos y su influencia en el crecimiento poblacional y el desarrollo de los espacios periurbanos en Calimaya, Estado de México, de 1990 a 2015. Papeles de población, 23(92), 217-243. doi: https://doi.org/10.22185/24487147.2017.92.018

Goddard, M., Dougill, A. J. & Benton, T. G. (2010). Scaling up from gardens: biodiversity conservation in urban environments. Trends Ecol Evol, 25(2), 90-98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.07.016

González-Ball, R., Bermúdez-Rojas, T. & Romero-Vargas, M. (2017). Floristic composition and richness of urban domestic gardens in three urban socioeconomic stratifications in the city Heredia, Costa Rica. Urban ecosystems, 20, 51-63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-016-0587-4

Gurrola-Hidalgo, M. A., Sánchez-Hernández, C. & Romero-Almaraz, M. L. (2009). Dos nuevos registros de alimentación de Quiscalus mexicanus y Cyanocorax sanblasianus en la costa de Chamela, Jalisco, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 25(2), 427-430. doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2009.252648

Hernández-Puig, S. (2016). El periurbano, un espacio estratégico de oportunidad. Revista Bibliográfica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, 21(1160). doi: https://doi.org/10.1344/b3w.0.2016.26341

MAG/INTA/FITTACORI/SUNII. (2015). Leyenda CLC-CR para la generación de mapas de uso y cobertura de la tierra de Costa Rica. (Leyenda Corine Land Cover Costa Rica V1.0) /Albán Rosales Ibarra. San José, Costa Rica. https://www.inta.go.cr/transferencia-de-tecnologia/publicaciones/manuales

Leyequien, E. & Toledo, V. M. (2009). Flores y aves de cafetales: Ensambles de biodiversidad en paisajes humanos. Biodiversitas, 83, 7-10.

Loram, A., Warren, P., Thompson, K. & Gaston, K. (2011). Urban domestic gardens: the effects of human interventions on garden composition. Environ Manage, 48(4), 808-824. doi: https://doi.org/10.0267/011-9723-3

Martínez-Cruz, A. L. & Sainz-Santamaría, J. (2017). El valor de dos espacios recreativos periurbanos en la Ciudad de México. El trimestre económico, 84(336), 805-846.

McKinney, M. L. (2002). Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation. BioScience, 52, (10), 883-890. doi: https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0883:UBAC]2.0.CO;2

Ministerio de Salud de Costa Rica. (2020). LS-SP-001 Lineamientos para el uso de espacios públicos al aire libre, incluidos los que poseen cerramiento perimetral, para fines recreativos y de actividad física. www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr

Murillo, O. (2005). Desmitificación del debate de especies exóticas y nativas. Ambientico, (141), 4-6.

Oliveira, M. T. P., Silva, J. L. S., Cruz-Neto, O., Borges, L. A., Girão L. C., Tabarelli, M. & Lopes, A. V. (2020). Urban green areas retain just a small fraction of tree reproductive diversity of the Atlantic Forest. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 54, 1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126779

Perepelizin, P. V. & Faggi, A. M. (2009). Diversidad de aves en tres barrios de la ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. MULTEQUINA, 18, 71-85.

Pineda-López, R., Malagamba-Rubio, A., Arce, I. & Ojeda, J. A. (2013). Detección de aves exóticas en parques urbanos del centro de México. Huitzil, 14(1), 56-67. doi: https://doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2013.14.1.174

Rodrigues, A. G., Borges-Martins, M. & Zilio, F. (2018). Bird diversity in an urban ecosystem: The role of local habitats in understanding the effects of urbanization. Iheringia Serie Zoología,108. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4766e2018017

Sánchez de Lorenzo-Cáceres, J. M. (2003). Algunas consideraciones sobre el árbol en el diseño urbano. Árboles ornamentales. http://www.arbolesornamentales.es/Arbolurbano.htm

Shochat, E., Lerman, S., & Fernandez-Juricic, E. (2010). Birds in urban ecosystems: population dynamics, community structure, biodiversity, and conservation. En J. Aitkenhead-Peterson & A. Volder (Eds.). Urban Ecosystem Ecology. American Society of Agronomy, Inc., Crop Science Society of America, Inc., Soil Science Society of America, Inc. doi: https://doi.org/10.2134/agronmonogr55.c4

Sorensen, M., Barzetti, V., Keipi. K. & Williams J. (1998). Manejo de las áreas verdes urbanas. Documento de Buenas prácticas. BID- Washington, D.C.

Styles, F. G. & Skutch, A. F. (2007). Guía de aves de Costa Rica. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial INBio.

Vasco, C. T., Bernal, V. V. & Soto, A. N. (2005). El borde como espacio articulador de la ciudad actual y su entorno. Revista Ingenierías Universidad de Medellín, 4(7), 55-65.

Villegas, M. & Garitano-Zavala, A. (2008). Las comunidades de aves como indicadores ecológicos para programas de monitoreo ambiental en la ciudad de La Paz, Bolivia. Ecología en Bolivia, 43(2), 146-153.

Yukhnovskyi V., & Zibtseva O. (2019). Normalization of green space as a component of ecological stability of a town. J. For. Sci., 65. 428-437. https://doi.org/10.17221/85/2019-JFS

1 Dra. Geógrafa. Escuela de Ciencias Geográficas, Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica. Correo electrónico: marilyn.romero.vargas@una.ac.cr ![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6840-5803

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6840-5803

2 M. Sc. Bióloga. Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica. Correo electrónico: tania.bermudez.rojas@una.ac.cr ![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7566-9521

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7566-9521

3 M. Sc. Biólogo. Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica. Correo electrónico alejandro.duran.apuy@una.ac.cr ![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6605-6048

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6605-6048

4 M. Sc. Geógrafo. Escuela de Ciencias Geográficas, Costa Rica. Correo electrónico: marvin.alfaro.sanchez@una.ac.cr ![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4962-1687

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4962-1687

5 Bach. Geógrafo. Escuela de Ciencias Geográficas, Costa Rica. Correo electrónico: sebastian.bonilla.soto@est.una.ac.cr ![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6292-9806

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6292-9806

Escuela de Ciencias Geográficas

Universidad Nacional, Campus Omar Dengo

Apartado postal: 86-3000. Heredia, Costa Rica

Teléfono: (506) 2562-3283

Correo electrónico revgeo@una.ac.cr