Escuela de Ciencias del Movimiento Humano y Calidad de Vida

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

e-ISSN: 1659-097X

Vol. 21(1), enero-junio, 2024

revistamhsalud@una.ac.cr

Licencia: By NC ND 3.0 Internacional

https://doi.org/10.15359/mhs.21-1.19168

Gender Differences in Physical Performance and Psychological Assessment Among Cuban National Athletics Team

Diferencias de género en el rendimiento físico y la evaluación psicológica en el equipo nacional de atletismo cubano

Diferenças de gênero no desempenho físico e avaliação psicológica entre a equipe nacional de atletismo de Cuba

Feria-Madueño, Adrián1, Montoya, César2, López, Larién3 y González-Carballido, Luis Gustavo4

ABSTRACT:

Introduction: Elite sports pose potential health risks, but are vital to the well-being of society. In Cuban society, sport is an integral part of personal development and public health, fostering unity and promoting female participation for sustainable growth. Athletics is one of the most important sports in Cuban sport, and should be approached both from the point of view of sports training and sports psychology. Purpose: The aim of this study was to provide a description of conditional variables in a countermovement jump (CMJ), mood profile, self-efficacy, and the leg-hip height index among athletes from the Cuban national athletics pre-selection team, differentiated by gender. Methods: Our sample consisted of the Cuban national athletics pre-selection team. Results: Mood profile analysis using the Profile of Mood States (POMS) did not reveal significant gender differences, with a small effect size for gender. Men showed a slightly greater trend towards vigor compared to women. Significant differences in self-efficacy were observed between men and women in their confidence levels to achieve jump heights between 21 and 40 cm using the CMJ. However, no significant differences were found for jumps exceeding 40 cm, highlighting the importance of strategies to enhance athletes’ psychological needs and self-efficacy. Conclusions: This study suggests that the association between tension-related anxiety and performance indicators related to jump height may play a crucial role in determining specific profiles in male and female Cuban athletes. Our comprehensive analysis contributes to understanding gender differences in performance factors. These findings provide valuable insights for future research and athlete development strategies.

Keywords: athlete, gender differences, physical performance

|

RESUMEN: Introducción: Los deportes de élite plantean riesgos potenciales para la salud, pero son vitales para el bienestar de la sociedad. En la sociedad cubana, el deporte forma parte integral del desarrollo personal y la salud pública, fomentando la unidad y promoviendo la participación femenina, para un crecimiento sostenible. El atletismo es uno de los deportes más importantes en el deporte cubano, y debe ser abordado tanto, desde el punto de vista del entrenamiento deportivo, como desde la psicología deportiva. Propósito: El objetivo de este estudio fue proporcionar una descripción de las variables condicionales en un salto con contramovimiento (CMJ, por sus siglas en inglés), el perfil anímico, la autoeficacia y el índice de altura pierna-cadera en atletas de la preselección nacional cubana de atletismo, diferenciados por sexo. Materiales y métodos: Nuestra muestra estuvo constituida por la preselección nacional de atletismo de Cuba. Resultados: El análisis del perfil del estado de ánimo mediante el Perfil de Estados de Ánimo (POMS) no reveló diferencias significativas entre sexos, con un tamaño del efecto pequeño para el sexo. Los hombres mostraron una tendencia ligeramente mayor hacia el vigor, en comparación con las mujeres. Se observaron diferencias significativas en la autoeficacia entre hombres y mujeres, en sus niveles de confianza para alcanzar alturas de salto de entre 21 y 40 cm utilizando el CMJ. Sin embargo, no se encontraron diferencias significativas para los saltos superiores a 40 cm, lo que pone de relieve la importancia de las estrategias para mejorar las necesidades psicológicas y la autoeficacia de los atletas. Conclusiones: Este estudio sugiere que, la asociación entre la ansiedad, relacionada con la tensión y los indicadores de rendimiento, vinculados con la altura del salto, pueden desempeñar un papel crucial en la determinación de perfiles específicos, en atletas cubanos, de ambos sexos. Nuestro análisis exhaustivo contribuye a comprender las diferencias de género en los factores de rendimiento. Estos hallazgos proporcionan valiosos conocimientos para futuras investigaciones y estrategias de desarrollo en atletas. Palabras clave: deportista, desempeño físico, diferencias de género |

RESUMO: Introdução: Os desportos de elite apresentam riscos potenciais para a saúde, mas são vitais para o bem-estar da sociedade. Na sociedade cubana, o desporto é parte integrante do desenvolvimento pessoal e da saúde pública, fomentando a unidade e promovendo a participação feminina para um crescimento sustentável. O atletismo é uma das modalidades mais importantes do desporto cubano e deve ser abordado tanto do ponto de vista do treino desportivo como da psicologia desportiva. Objetivo: O objetivo deste estudo foi fornecer uma descrição das variáveis condicionais em um salto com movimento (CMJ, sigla em inglês), perfil de humor, autoeficácia e o índice de altura da perna-quadril entre atletas da equipe de pré-seleção nacional de atletismo de Cuba, diferenciados por gênero. Métodos: Nossa amostra consistiu na equipe de pré-seleção nacional de atletismo de Cuba. Resultados: A análise do perfil de humor usando o Perfil de Estados de Humor (POMS) não revelou diferenças significativas de gênero, com um pequeno efeito de tamanho para o gênero. Os homens mostraram uma tendência ligeiramente maior para o vigor em comparação com as mulheres. Diferenças significativas na autoeficácia foram observadas entre homens e mulheres em seus níveis de confiança para alcançar alturas de salto entre 21 e 40 cm usando o CMJ. No entanto, não foram encontradas diferenças significativas para saltos superiores a 40 cm, destacando a importância de estratégias para aprimorar as necessidades psicológicas e a autoeficácia dos atletas. Conclusões: Este estudo sugere que a associação entre ansiedade relacionada à tensão e indicadores de desempenho relacionados à altura do salto pode desempenhar um papel crucial na determinação de perfis específicos em atletas cubanos do sexo masculino e feminino. Nossa análise abrangente contribui para entender as diferenças de gênero nos fatores de desempenho. Esses achados fornecem insights valiosos para futuras pesquisas e estratégias de desenvolvimento de atletas. Palavras-chave: atleta, desempenho físico, diferenças de gênero |

Elite sports play a significant role in societies worldwide, contributing to the promotion of sports engagement. Despite the potential risks to physical and mental health, the existence of elite sports is deemed necessary due to the positive impact it has on contemporary societies (González-Carballido & Ordoqui, 2023).

In Cuban society, sports are recognized as integral to personal development and the cultivation of values such as teamwork, discipline, perseverance, and competitiveness (Carter, 2009). Additionally, sports serve as a powerful tool for promoting public health and well-being, playing a crucial role in disease prevention and the maintenance of a healthy lifestyle. The remarkable achievements of Cuban athletes have fostered a sense of celebration and admiration nationwide, contributing to a strong sense of unity and social cohesion. To ensure the sustainable growth of elite sports in Cuba, it is essential to understand key factors such as sports infrastructure, the exceptional training of coaches, and the institutional support provided to athletes. Moreover, active participation in sports continues to be encouraged, with a particular emphasis on promoting female involvement, which enhances opportunities for access, professional development, and empowerment (Huish et al., 2013).

In the field of athletics, there has been a growing interest in studies linking psychological variables to physical performance in recent years (Berenguí & Castejón, 2021; Casado et al., 2014). For instance, (Montoya et al., 2020) investigated the relationship between self-efficacy, mood, and performance in throwing athletes, finding significant correlations between self-efficacy and tension (r = -.479, p = 0.045), self-efficacy and vigor (r = .322, p = 0.192), and self-efficacy and fatigue (r = -.442, p = 0.66), with only the tension correlation being statistically significant. Despite studies linking psychological variables to athletic performance in elite athletics, there is a scarcity of research explaining this relationship in specific performance control tasks or training loads during workouts.

In athletics, various methods are used to assess performance (Jiménez-Reyes et al., 2011; Portuondo et al., 2022), with one of the most commonly employed being jump testing, particularly the countermovement jump (CMJ) test, which is strongly associated with athletes’ sports performance and is used as a method to control training load (Claudino et al., 2012) and identify sporting talent (Fry et al., 2006; Gabbett et al., 2007; Petridis et al., 2019).

In this context, the use of mental strategies before jump execution has been studied. Feltz (1982) demonstrated that self-efficacy was a significant predictor of the outcome of the first of four jump attempts, and subsequent attempts were influenced by previous results. Edwards et al. (2008) examined the positive effects of instructive and motivational internal dialogue on the displacement of the center of mass and hip kinematics during vertical jumping in male rugby players. However, there have been limited investigations regarding the relationship between mood, self-efficacy, and vertical jumping as a method of monitoring training load in elite track and field athletes (Lochbaum et al., 2021).

Thus, sports in Cuba continue to be a crucial component of health and education initiatives, with a continued focus on sports development as a national priority. Over the years, Cuba has achieved international excellence in various sports disciplines, garnering numerous successes and accolades. Athletics, in particular, stands out as a prominent sport at the international level, as evidenced by the recently concluded Central American Games held in San Salvador. The objective of this study was to provide a descriptive analysis of the sports profile of the Cuban athletics pre-selection based on performance and psychological variables.

This study employed a quantitative approach and utilized a cross-sectional and descriptive study design.

The sample comprised 20 individuals from the Cuban national athletics team. The study was conducted during the national pre-selection phase in November 2018. The inclusion criteria required participants to be free of lower limb injuries in the past 6 months and within the age range of 15 to 17 years at the time of evaluation. After applying these criteria, the final sample consisted of 8 females (age = 16 [±0.92] years; Body Mass Index - BMI - = 22.68 [±0.99] Kg/m2) and 6 males (age = 16 [±0.77] years; BMI = 23.45 [±1.07] Kg/m2) (Table 1).

Table 1

Description of variables

|

N |

Age (years) |

Force (N) |

Height (m) |

Leg length-hip height index at 90º |

Months of experience |

|

|

Men |

6 |

16.33 ± 0.77 |

720.30 ± 29.67 |

1.80 ± 0.11 |

0.42 ± 0.004 |

49.20 ± 1.95 |

|

Women |

8 |

16.13 ± 0.92 |

703.68 ± 32.55 |

1.75 ± 0.13 |

0.40 ± 0.005 |

43.20 ± 2.16 |

Note. Data shown in mean ± SD. N = Newtons; m = meters; Kg/m2 = Kilograms of mass as a function of meters of surface area.

Participants voluntarily participated in the study and provided informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Sports Medicine Institute in Havana, in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Physical fitness parameters, including strength, jump height, power, and velocity during a vertical jump, were evaluated. Psychological aspects such as mood profile and self-efficacy were also assessed in the participating athletes.

Vertical jump performance was assessed using the Countermovement Jump (CMJ) task. Participants executed each CMJ from a stationary position with hands on their hips. During the flight phase of the jump, participants maintained straight knees, and both feet landed simultaneously. The CMJ was evaluated using the validated method by Balsalobre-Fernández, et al. (2015) through the Myjump 2 mobile application. An adjudicator recorded the jumps using a portable recording device positioned two meters away from the competitors (Apple Inc. iPhone 5s America smartphone). Participants were instructed to perform the jumps upon receiving “Go” signals, and the jump data was subsequently processed within the application. Takeoff and landing times were manually recorded. The CMJ assessment included specific variables of interest such as jump height, flight time, velocity, power, and performance.

The Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire was utilized to analyze the mood profile, given its utility in athletes (McNair et al., 1992). The short version of the POMS (Grove & Prapavessis, 1992) was employed, which had been adapted for Cuban athletes (Barrios-Duarte, 2011). The questionnaire consisted of six items, including: a) feelings of anxiety, restlessness, and uneasiness; b) feelings of sadness, discouragement, and depression; c) feelings of anger, fury, and a bad mood; d) feelings of being active, joyful, and full of energy; e) feelings of exhaustion, tiredness, and fatigue; f) feelings of insecurity, disorientation, and inability to concentrate. The questionnaire was administered individually immediately before the CMJ performance.

In order to assess self-efficacy, the self-efficacy scale was used (Bandura, 2006). Each athlete responded to three different questions assessing their confidence levels regarding their ability to exceed 20 cm of height, jump more than 20 cm without exceeding 39 cm, and jump more than 40 cm. The possible responses ranged from 0 to 5, with athletes providing a numerical value representing their confidence level. A score of 5 represented “completely confident,” 4 represented “very confident,” 3 represented “quite confident,” 2 represented “somewhat confident,” 1 represented “not very confident,” and 0 represented “not at all confident.”

Leg Length to Hip Height Index

The leg length to hip height index in a 90° position was evaluated in all athletes following the guidelines of the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK). Measurements were taken using a measuring tape (SECA 206) with a precision of 1 mm.

All athletes were assessed for performance variables related to physical fitness parameters and psychological aspects. Mood state and self-efficacy were analyzed based on subjective performance perception. Subsequently, leg length and hip height at 90° were measured. Following the measurements, athletes performed a standardized warm-up consisting of joint mobility exercises and 15 familiarization CMJs. Two CMJs were then evaluated using the Myjump 2 app, and the jump with the highest achieved height was selected for analysis. The order of participation was randomized between males and females, and no athlete reported any discomfort during the test. All data were recorded prior to the commencement of the training session.

Data Analysis

A Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to assess the normality of the variables. The mean and standard deviation were calculated, and Student’s t-tests were used to compare between males and females. The statistical package Jamovi 2.3.21 was employed for the analysis. Finally, the effect size was analyzed using Cohen’s d with a 95% confidence interval, considering a small effect for d = .2, a moderate effect for d = .5, and a large effect for d = .8.

The normality of the variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test, indicating that the variables were non-parametric. Descriptive data for both male and female athletes, including CMJ and mood profile, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Descriptive data of CMJ variables and mood profile

|

Variables |

Men |

Women |

p |

d |

|

Height (cm) |

38.77 ± 4.28 |

42.92 ± 9.34 |

.196 |

.438 |

|

Flight time (ms) |

562.50 ± 31.12 |

591.50 ± 61.07 |

.109 |

.417 |

|

Speed (m*s2) |

1.38 ± 0.07 |

1.45 ± 0.15 |

.109 |

.417 |

|

Force (N) |

2624.73 ± 194.73 |

2813.56 ± 423.42 |

.098 |

.438 |

|

Power (W) |

3621.48 ± 469.45 |

4084.75 ± 1105.87 |

.098 |

.438 |

|

Anxiety |

1.50 ± 0.81 |

2.00 ± 1.41 |

.44 |

.06 |

|

Sadness |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

.23 |

.12 |

|

Furious |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

0.25 ± 0.70 |

.23 |

.12 |

|

Vigorous |

3.83 ± 0.40 |

3.62 ± 1.06 |

.50 |

.02 |

|

Tired |

0.66 ± 0.81 |

0.12 ± 0.35 |

.59 |

.04 |

|

Insecure |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

- |

- |

Note. Data shown in median ± SD. Cm = centimeters; ms = milliseconds; m*s2 = meters per second squared; N = newtons; W = watts; p = Mann-Whitney U test; d = Cohen’s measure of sample effect size for comparing two sample means.

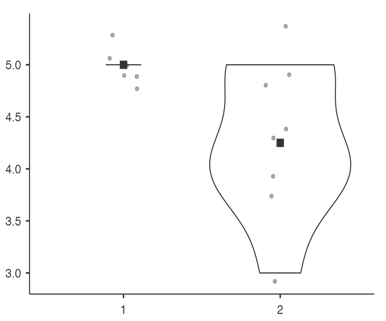

Regarding self-efficacy, Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of values among male and female athletes in diagram form (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Violin plot of self-efficacy by gender

A

A B

B C

C

Notes. 1 = males; 2 = females; A = Self-efficacy to jump safely between 20 and 40 centimeters; B = Self-efficacy to jump safely over 40 centimeters; C = Total self-efficacy.

Regarding self-efficacy, significant gender differences were found only in relation to the safety of jumping between 21 and 40 cm (males = 5.00 ± 0.00, females = 4.00 ± 0.70, p = .02, d = .62). No significant differences were observed for self-efficacy in jumping over 40 centimeters (males = 4.00 ± 0.51, females = 4.00 ± 0.94, p =.72, d = .12) or for total self-efficacy (males = 27.80 ± 1.72, females = 25.60 ± 4.24, p = .85, d = .31).

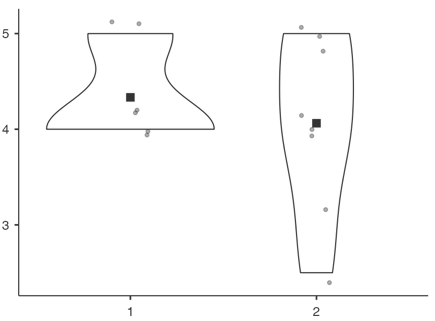

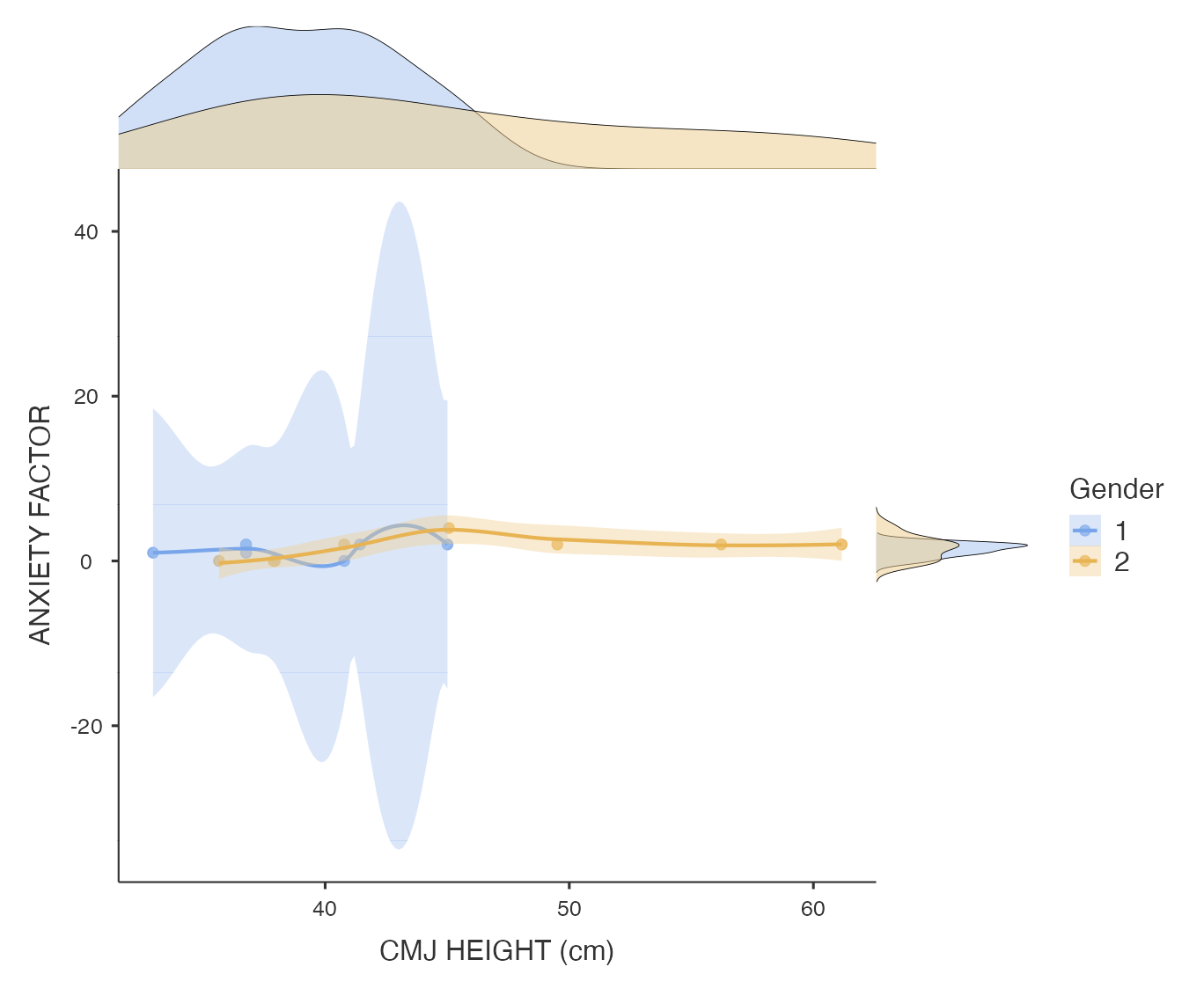

Furthermore, the variables of countermovement jump (CMJ) were examined in relation to mood profile and self-efficacy. Figure 2 illustrates the differences between male and female athletes in terms of CMJ height and the anxiety factor of the mood state (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Dispersion of CMJ height in relation to the anxiety factor among genders

Notes. 1 = males; 2 = females

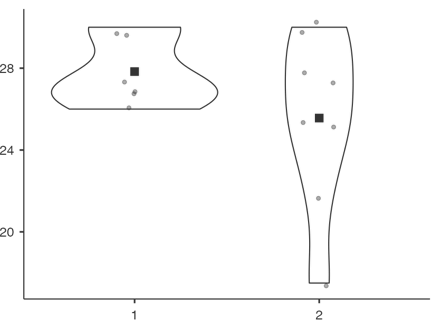

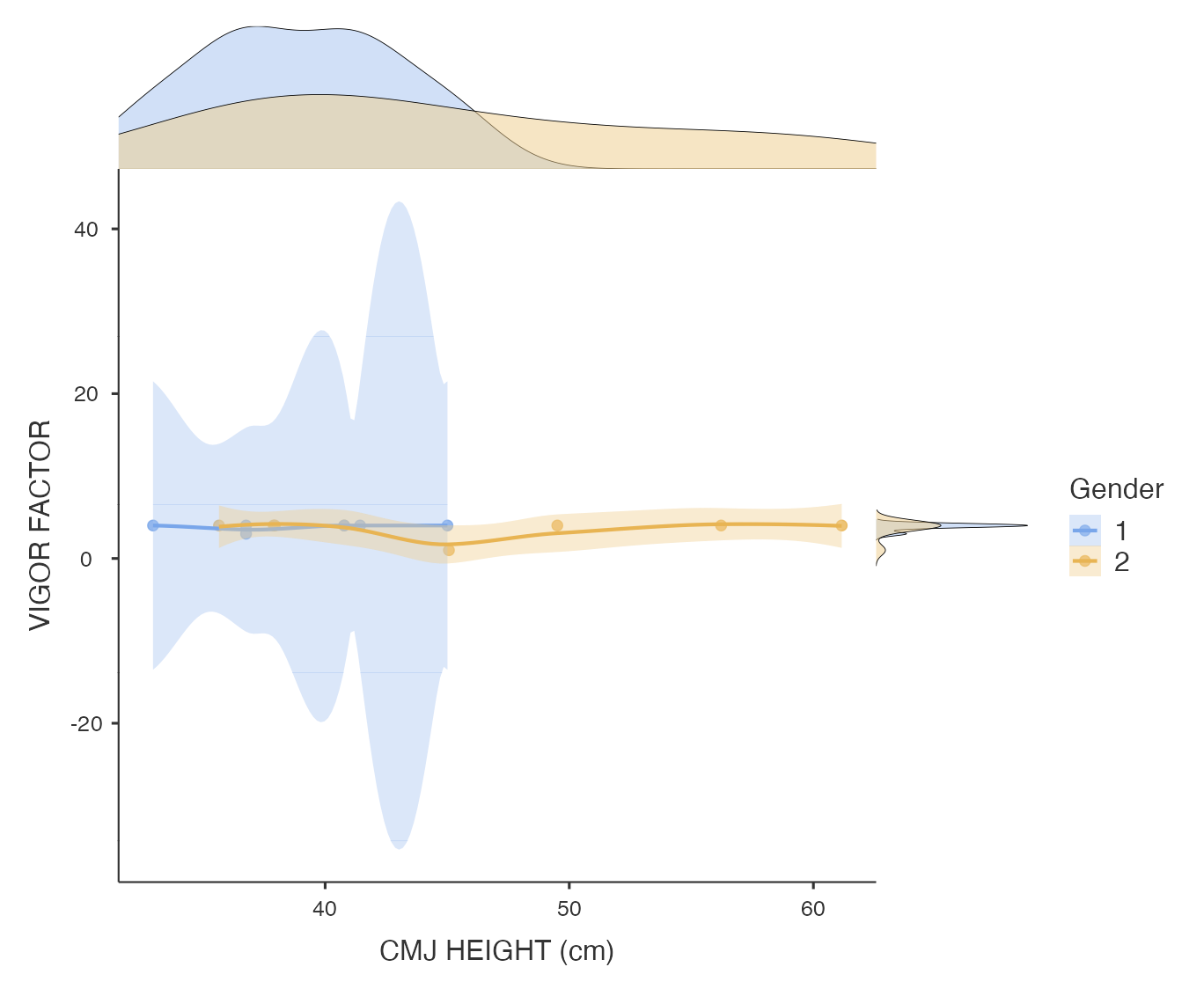

On the other hand, the dispersion of CMJ height in relation to the vigor factor of the POMS can be observed among genders (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Dispersion of CMJ height in relation to the vigor factor among genders

Notes. 1 = males; 2 = females

The aim of this study was to provide a description of conditional variables in a CMJ, mood profile, self-efficacy, and the leg-hip height index among athletes from the Cuban national athletics’ pre-selection team, differentiated by gender. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess performance factors through vertical jumping using CMJ, mood profile, and self-efficacy in Cuban track and field athletes. The main findings suggest that both male and female athletes present a similar competitive sports profile, with no significant differences observed.

Proper interpretation of the information provided by the CMJ reflects the analysis of strength levels (McLean et al., 2011), training status (Gathercole et al., 2015), and even athlete fatigue (Armada-Cortés et al., 2022). This is due to its close relationship with other metabolic variables such as lactate and ammonia accumulation, as well as mechanical variables like loss of speed (Balsalobre-Fernández et al., 2015), among others. Previous studies have established that among the indicators measured by the test, the average jump height represents the main reference. In a meta-analysis that included 151 articles, 85.4% of them used the maximum CMJ height, 13.2% used the average height, and 1.3% used both. However, the average CMJ height was found to be more sensitive than the maximum height in detecting fatigue and supercompensation (Claudino et al., 2012). In our study, although women showed higher results than men in specific CMJ-derived variables, these differences were not statistically significant (p > .05). However, the effect size suggests that gender has a small to moderate effect on height (d = .43), flight time (d = .41), velocity (d = .41), strength (d = .43), and power (d = .43) variables. These findings contradict those reported in the literature (Davies et al., 2018). One possible explanation for the lack of differences in this case may lie in what was described by Cuba-Dorado et al. (2022), who found no differences in muscle contractile properties between male and female triathlon athletes through tensiomyography analysis.

Furthermore, our sample consisted of the Cuban national athletics pre-selection team, with a mean age of 16.33 ± 0.77 years for males and 16.13 ± 0.92 years for females. At these ages, the developmental factor towards adulthood seems to be a determinant for the analysis of CMJ-derived variables, as reflected in the study by Bassa et al. (2012).

In terms of the mood profile, no significant differences were found between men and women in the analysis performed using the Profile of Mood States (POMS) (p > .05), with a small effect size for gender (d < .2). However, there was a greater trend towards vigor in men compared to women. Our data align with recent findings by Reynoso-Sánchez et al. (2021), who found a higher vigor factor in young Mexican athletes. However, the same did not apply to the anxiety factor, where women showed a higher but not significant value compared to men (p = .44, d = .06).

Regarding self-efficacy, our results showed significant differences between men and women in terms of their confidence in achieving a jump height between 21 and 40 centimeters using the CMJ (p = .02, d = .62). These findings can be related to those explained by Di Fronso et al. (2013), who found an increase in self-efficacy in men compared to women during the preparation phases in basketball players. In our study, we observed significant differences only for jumps between 21-40 centimeters. This can be considered as a sub-phase for subsequent jumps over 40 centimeters, where no significant differences were found (p > .05). One possible response to help athletes find strategies that satisfy their psychological needs of self-efficacy may be addressed by Isorna-Folgar et al. (2022), who recently found an effective cognitive intervention program for rowers from the Spanish national junior team.

On the other hand, our results suggest that the association between tension-related anxiety and performance indicators related to jump height may be decisive in finding specific profiles in male and female athletes in Cuban athletics. (Lane et al., 2001) analyzed the relationship between mood profile and sports performance. An important finding to consider is that the anxiety factor correlates positively with performance. Our results demonstrate the dispersion between anxiety and jump height, although they do not reflect significant differences between genders (p > .05). The correct interpretation of the relationship between anxiety and performance found in this intensive study (Rice et al., 2019) requires a return to the essential theoretical assumptions that correspond to models dealing with anxiety. Yerkes & Dodson’s Inverted U Hypothesis argues for the existence of an optimal level of activation or arousal to achieve maximum performance (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). Activation presupposes an energetic state of the organism that allows for a particular function, such as a state of readiness for action. This state depends on stimulus conditions (Pozo et al., 2013) and can vary depending on the autonomic nervous system. The value of anxiety factors related to jump performance found in this study can be interpreted under this premise, as the nervous system predisposes the athlete based on the performance goal. In our case, the goal was to jump as high as possible using the CMJ and to determine the athlete’s confidence at different heights. (Sanchez et al., 2010) demonstrated higher levels of anxiety and their relationship to performance. The researchers concluded that the psychological state preceding competition seems to be an important factor in its success.

Another model that addresses the relationship between anxiety and performance is the Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning (IZOF) model (Hanin, 1995). This model assumes a functional relationship between emotion and optimal performance and aims to predict emotional quality in relation to the performer’s previous emotional state. The model takes into account different performance outcomes of quality and associated emotional intensity. The development of this method is the first step toward developing models that consider the multidimensionality of interactive traits and emotional structures. De Andrade et al. (2019) applied this model to elite athletes and found an association between anxiety related to exercise performance and self-efficacy. In this sense, proper management of anxiety may be related to better control of emotional intelligence in individuals engaged in physical activity (Castro-Sánchez et al., 2022).

Finally, the relationship between vigor and jump height was also analyzed in the present study. In the observed dispersion, it is interesting to consider the vigor mood factor before performing a motor gesture related to athlete performance, such as CMJ jump height. In a recent meta-analysis, (Lochbaum et al., 2021) discussed the relationship between athlete mood profile and exercise performance. These authors emphasized the importance of understanding the mood profile of an athlete and its relationship to sports performance, providing an integrated view using the POMS scale as a predictor of athlete performance. According to our results, men exhibited higher levels of vigor than women. Despite finding an increase in the vigor factor, the jump height results were higher in women, although not statistically significant (p > .05). One possible explanation for the relationship between mood profile control and sports performance could be the increased likelihood of sports injury (Van Wilgen et al., 2010). Jump landings can be associated with sports injuries, and gender differences have been observed from a kinematic and kinetic perspective (Sañudo et al., 2012). Although the present study did not assess the relative risk of injury, it appears crucial to control the vigor factor of the mood profile during sports tests such as the CMJ, not only due to its association with injuries (Van Wilgen et al., 2010), but also its relationship with test performance (Lochbaum et al., 2021).

Both male and female athletes showed relatively similar performance, although a moderate gender effect on jump variables was observed for women. Regarding mood factors, there were no significant differences. However, men exhibited significantly higher self-confidence values than women to reach heights between 21 and 40 cm. Finally, associations were found between the anxiety factor and CMJ height, as well as the vigor factor and CMJ height. This study suggests that the association between tension-related anxiety and performance indicators related to jump height may play a crucial role in determining specific profiles in Cuban athletes of both sexes. Our comprehensive analysis contributes to understanding gender differences in performance factors. These findings provide valuable insights for future research and athlete development strategies.

Armada-Cortés, E., Benitez-Muñoz, J. A., San-Juan, A. F., & Sánchez-Sánchez, J. (2022). Evaluation of neuromuscular fatigue in a repeat sprint ability, countermovement jump and hamstring test in elite female soccer players. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15069. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215069.

Balsalobre-Fernández, C., Glaister, M., & Lockey, R. A. (2015). The validity and reliability of an iPhone app for measuring vertical jump performance. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(15), 1574–1579. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.996184.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307–337). Information Age Publishing. https://acortar.link/5rlajm

Barrios-Duarte, R. (2011). Elaboración de un instrumento para evaluar estados de ánimo en deportistas de alto rendimiento. [Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad de Ciencias de la Cultura Física y el Deporte]. Repositorio de tesis en ciencias biomédicas y de la salud de Cuba. https://tesis.sld.cu/index.php/index.php?P=FullRecord&ID=320&ReturnText=Search+Results&ReturnTo=index.php%3FP%3DAdvancedSearch%26Q%3DY%26G67%3D181%26RP%3D5%26SF%3D62%26SD%3D%26SR%3D35

Bassa, E. I., Patikas, D. a., Panagiotidou, A. I., Papadopoulou, S. D., Pylianidis, T. C., & Kotzamanidis, C. M. (2012). The effect of dropping height on jumping performance in trained and untrained prepubertal boys and girls. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(8), 2258–2264. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823c4172

Berenguí, R. & Castejón, M. A. (2021). Desensibilización sistemática para el control de la ansiedad: Un caso de atletismo. Revista de Psicología Aplicada al deporte y al Ejercicio Físico, 6(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.5093/rpade2021a13

Carter, T. F. (2009). ¿Hasta la victoria siempre? The Evolution and Future of Revolutionary Sport. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research, 15(2), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13260219.2009.11090848

Casado, A. A., Ruiz-Pérez, L. M., & Graupera, J. L. (2014). La percepción que los corredores kenianos tienen de sus actividades entrenamiento. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 14(2), 99-110. https://doi.org/10.4321/S1578-84232014000200011

Castro-Sánchez, M., Ramiro-Sánchez, T., García Mármol, E., & Chacón-Cuberos, R. (2022). The association of trait emotional intelligence with the levels of anxiety, stress and physical activity engagement of adolescents. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 54, 130-139. https://doi.org/10.14349/rpl.2022.v54.15

Claudino, J. G., Mezêncio, B., Soncin, R., Ferreira, J. C., Couto, B. P., & Szmuchrowski, L. A. (2012). Pre vertical jump performance to regulate the training volume. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 33(2), 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1286293

Cuba-Dorado, A., Alverez- Yates, T., Carballo- López, J., Iglesias- Caamaño, M., Fernández- Redondo, D., & García- García, O. (2022). Neuromuscular changes after a long distance triathlon world championship. European Journal of Sport Science, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2022.2134053

Davies, R. W., Carson, B., P., & Jakeman, P. M. (2018). Sex differences in the temporal recovery of neuromuscular funtion following resistance training in resistance trainet men and woman 18 to 35 years. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1480). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg/2018.01480

De Andrade, F. C., Gattás, M. & Moura, L. (2019). Application of izof model for anxiety and self-efficacy in volleyball athletes: a case study. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte, 25(4), 338-343. https://doi.org/10.1590/1517-869220192504211038

Di Fronso, S., Nakamura, F. Y., Bortoli, L., Robazza, C., & Bertollo, M. (2013). Stress and recovery balance in amateur basketball players: differences by gender and preparation phase. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 8(6), 618–622. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.8.6.618

Edwards, C., Tod, D., & McGuigan, M. (2008). Self-talk influences vertical jump performance and kinematics in male rugby union players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 26(13), 1459-1465. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802287071

Feltz, D. L. (1982). Path analysis of the causal elements in Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy and an anxiety-based model of avoidance behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(4), 764-781. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.4.764

Fry, A. C., Ciroslan, D., Fry, M. D., LeRoux, C. D., Schilling, B. K., & Chiu, L. Z. (2006). Anthropometric and performance variables discriminating elite American junior men weightlifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(4), 861-866. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-18355.1

Gabbett, T., Georgieff, B., & Domrow, N. (2007). The use of physiological, anthropometric, and skill data to predict selection in a talent-identified junior volleyball squad. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(12), 1337-1344. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410601188777

Gathercole, R. J., Stellingwerff, T., & Sporer, B. C. (2015). Effect of acute fatigue and training adaptation on countermovement jump performance in elite snowboard cross athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000622

González-Carballido, L.G., & Ordoqui, J.A. (2023). Salud mental en el deporte de alto rendimiento. Revista Cubana de Psicología, 5(7). https://revistas.uh.cu/psicocuba/article/view/6950

Grove, J. R. & Prapavessis, H. (1992). Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of an abbreviated profile of mood states. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 23(2), 93–109. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-15924-001

Hanin, Y. (1995). Individual zones of optimal functioning (IZOF) model: an idiographic approach to performance anxiety. In K. Henschen & W. Straub (Eds.), Sport psychology: An analysis of athlete behavior (pp. 103-119). Mouvement Publication.

Huish, R., Carter, T. F., &. Darnell, S. C. (2013). The (soft) power of sport: the comprehensive and contradictory strategies of Cuba’s sport-based internationalism. International Journal of Cuban Studies, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.13169/intejcubastud.5.1.0026

Isorna-Folgar, M., Leirós-Rodríguez, R., López-Roel, S., & García-Soidán, J. L. (2022). Effects of a cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention on the rowers of the junior spain national team. Healthcare, 10(12), 2357. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122357

Jiménez-Reyes, P., Cuadrado-Peñafiel, V., & González-Badillo, J. J. (2011). Analysis of variables measured in vertical jump related to athletic performance and its application to training. Cultura, Ciencia, Deporte (CCD) 6(17). https://doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v6i17.38

Lane, A. M., Terry, P. C., Beedie, C. J., Curry, D. A., & Clark, N. (2001). Mood and performance: Test of a conceptual model with a focus on depressed mood. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 2(3), 157-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(01)00007-3

Lochbaum, M., Zanatta, T., Kirschling, D., & May, E. (2021). The profile of moods states and athletic performance: A meta-analysis of published studies. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(1), 50-70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11010005

McLean, S. G., Oh, Y. K., Palmer, M. K., Lucey, S. M., Lucarelli, D. G., Ashton- Miller, J. A., & Wojtys, E. M. (2011). The Relationship between anterior tibial acceleration, tibial slope, and ACL strain during a simulated jump landing task. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 93(14), 1310–1317. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.J.00259

McNair D., Lorr M., & Droppleman L. (1992). Profile of Mood States Manual (rev.). San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service.

Montoya, C. A., González, L. G., Sánchez, J. E., & Chavez, C. O. (2020). Dinámica de autoeficacia, ansiedad, perfil anímico y rendimiento deportivo en lanzadores cubanos de atletismo. In T. Trujillo (Ed.) Teoría y práctica de la psicología del deporte en Iberoamérica (pp. 86-95). Independently published. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_nlinks&pid=S0120-0534202300010016000039&lng=en

Petridis, L., Utczás, K., Tróznai, Z., Kalabiska, I., Pálinkás, G., & Szabó, T. (2019). Vertical jump performance in Hungarian male elite junior soccer players. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 90(2), 251-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2019.1588934

Portuondo, M. E., Mendoza, J. E., Rodríguez, A., & Vicente, H. O. (2022). Propuesta metodológica para control de la preparación somática y física en alumnos de atletismo. Revista Sociedad & Tecnología, 5(S2), 415-430. https://doi.org/10.51247/st.v5iS2.280

Pozo, A., Cortes, B., & Pastor, Á.M. (2013). Conductancia de la piel en deportes de precisión y deportes de equipo. Estudio preliminar, Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 19–28. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=235127552004

Reynoso-Sánchez, L. F., Pérez-Verduzco, G., Celestino-Sánchez, M. Á., López-Walle, J. M., Zamarripa, J., Rangel-Colmenero, B. R., Muñoz-Helú, H., & Hernández-Cruz, G. (2021). Competitive Recovery-Stress and Mood States in Mexican Youth Athletes. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 627828. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.627828

Rice, S. M., Gwyther, K., Santesteban-Echarri, O., Baron, D., Gorczynski, P., Gouttebarge, V., Reardon, C. L., Hitchcock, M. E., Hainline, B., & Purcell, R. (2019). Determinants of anxiety in elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine, 53(11), 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100620

Sanchez, X., Boschker, M. S., & Llewellyn, D. J. (2010). Pre-performance psychological states and performance in an elite climbing competition. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 20(2), 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00904.x

Sañudo, B., Feria, A., Carrasco, L., de Hoyo, M., Santos, R., & Gamboa, H. (2012). Gender differences in knee stability in response to whole-body vibration. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 26(8), 2156–2165. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823b0716

van Wilgen, C. P., Kaptein, A. A., & Brink, M. S. (2010). Illness perceptions and mood states are associated with injury-related outcomes in athletes. Disability and rehabilitation, 32(19), 1576–1585. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638281003596857

Yerkes R. M., Dodson J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.920180503

The authors would like to thank all the people who made the development of this research possible. In addition, it is stated that no funding was received for this study.

AUTHOR´S CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

Author 1 participated in the conceptualization (lead), research, methodological design, data curation, writing of the manuscript (lead). Author 2 participated in conceptualization (support), data analysis (support), project management (support), review (support) and editing of the final manuscript. Author 3 participated in the drafting of the manuscript (support) and data analysis (lead). Author 4 participated in project management (lead) and revision (lead). All the authors participated in the preparation of this article.

Recibido 3-11-2023 - Aceptado 19-3-2024

1

0000-0001-7425-8694 Universidad de Sevilla, Departamento de Educación Física y Deporte, Sevilla, España. aferia1@us.es

0000-0001-7425-8694 Universidad de Sevilla, Departamento de Educación Física y Deporte, Sevilla, España. aferia1@us.es

2

0000-0001-6950-0503 Instituto de Medicina Deportiva, La Habana, Cuba. cmontoyaromero@gmail.com

0000-0001-6950-0503 Instituto de Medicina Deportiva, La Habana, Cuba. cmontoyaromero@gmail.com

3

0000-0002-5058-7378 Instituto de Medicina Deportiva, La Habana, Cuba. larien1231@gmail.com

0000-0002-5058-7378 Instituto de Medicina Deportiva, La Habana, Cuba. larien1231@gmail.com

4

0000-0003-3275-6366 Instituto de Medicina Deportiva, La Habana, Cuba. lgus_cu@yahoo.es

0000-0003-3275-6366 Instituto de Medicina Deportiva, La Habana, Cuba. lgus_cu@yahoo.es

Escuela de Ciencias del Movimiento Humano y Calidad de Vida

Benjamín Nuñez Campus, Universidad Nacional, Lagunilla, Heredia, Costa Rica

PO Box: 86-3000. Heredia, Costa Rica

Phone: (506) 2562-6980

E-mail revistamhsalud@una.ac.cr